A Chavez-style socialist who seeks to impose ruinous policies leads Peru’s upcoming election, putting human rights under threat.

Self-described Marxist-Leninist Pedro Castillo – a far-left socially conservative authoritarian with plans to suppress the media and withdraw protection for gender rights – is currently on course to win Peru’s upcoming election on June 6.

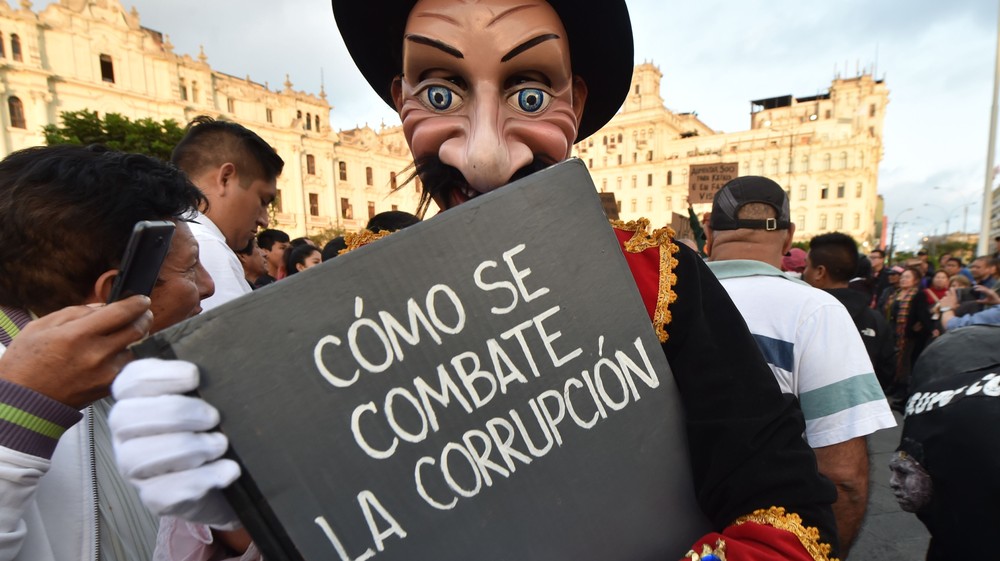

At present, the dissident union leader is the top contender for president, after surprisingly beating 17 other candidates earlier this month. Castillo has tapped into a wave of anti-establishment sentiment in order to win over those frustrated with Peru’s political system.

He is promising to abolish the constitutional court, nationalise the country’s vast mining gas, oil, and hydro-energy sectors, as well as put in place an agrarian reform which might involve land redistribution.

It’s all part of the Libre platform’s call for an economic transformation which echoes that of Venezuela prior to its downfall.

Castillo is likely headed into a runoff with Keiko Fujimori, daughter of Alberto Fujimori, who was incarcerated in 2007 for directing death squads to carry out two massacres of suspected terrorists.

He is also on trial for the forced sterilisations of thousands of poor indigenous women. Either pairing would amount in a highly polarised second-round, the results of which have the potential to steer the nation in radically different directions.

Voters are now trapped between two extreme ideologies.

‘Peruvians joke they have been long accustomed to voting for the mal menor (lesser evil), but that concept has been overtaken,’ says political analyst, Hernán Chaparro. ‘There’s not even a least bad one – the people voting don’t want any of them.’

In fact, according to a poll by the Institute of Peruvian Studies, 28% of Peruvians would not choose any of the candidates, deeming them all unfit to bring Peru out of the de facto parliamentary democracy it has gradually morphed into.

In recent months, Peru has gone through as many presidents as neighbouring Ecuador has in the past 14 years.

‘In the past, we’ve had a fragile democracy in Peru,’ adds Chaparro. ‘But now it’s in intensive care.’

Not only this, but other research shows that amid a spate of political crises, the handling of the pandemic by three different presidents has deepened their unhappiness. While voting is compulsory in Peru, turnout for this election is expected to be significantly lower than in previous years because Peruvians are tired of corruption and ineffective governance.