In a region where machismo reigns and gender-based violence is widespread, demonstrations against these issues continue to unfold. Now, the fight is crossing borders.

Deemed the most lethal location on the planet for women prior to the outbreak, Latin America is as deadly as ever, with activists of the #NiUnaMenos movement blaming Coronavirus for consolidating the ongoing problem of domestic and gendered violence throughout the region.

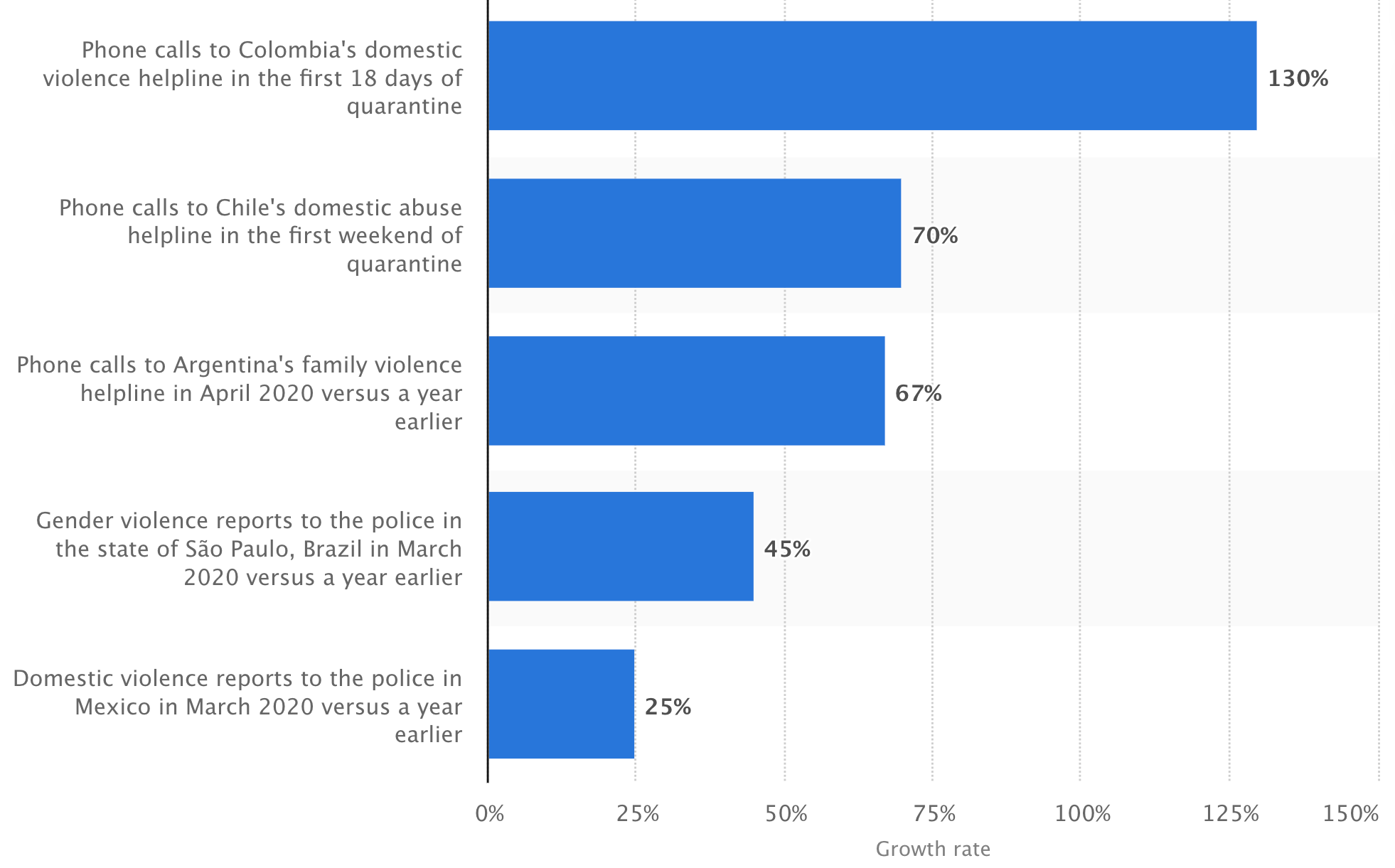

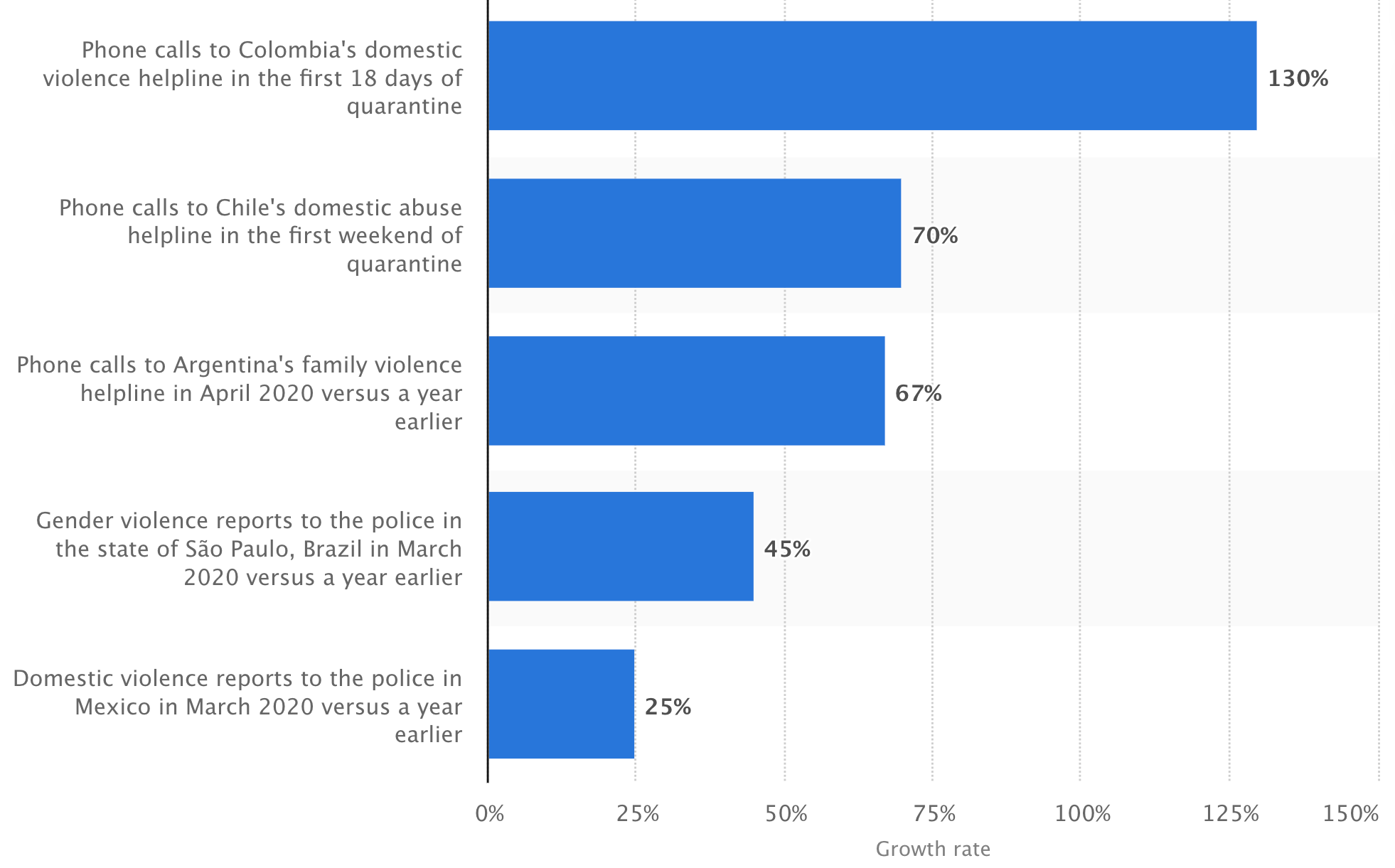

Comprising almost half of the world’s worst offending countries, fears that government-imposed quarantines would put countless women in danger were justified after Colombia alone saw an instantaneous 50% surge in reports of abuse the moment female citizens were instructed to stay indoors.

According to the UN, while an average of twelve Latin American women a day were subject to femicide in 2018, the current reality is much worse, further aggravated by the pandemic which brought about the murder of 18 Argentinian women by their partners in the first 20 days of lockdown, and a 65% increase of corresponding cases in Venezuela.

Earlier this year, Puerto Rico declared a state of emergency over the alarming number of women murdered, as activists report that at least 303 women were killed in the last five years.

In February, the murder of 18-year-old Ursula Bahillo pushed thousands into the streets of Buenos Aires to protest femicide in the country. In Honduras, a woman has been killed every 36 hours so far this year. In Mexico, at least 939 women were victims of femicide last year alone.

As this new wave of violence triggered by the unavoidable requirement to isolate continues to hit the region with brute force, campaigners like Arussi Unda, leader of Mexican feminist organisation Brujas del Mar, say that 2020 catapulted the existing crisis into irrefutable tragedy, with uncertainty posing an added threat.

‘We’re terrified because we don’t know how long this is going to last,’ she says. ‘Women are already in vulnerable positions so it’s even more complicated when their rights – such as the right to move freely – are restricted, in countries where the right to live a life free of violence is not guaranteed.’

Amidst what’s being locally referred to as ‘the other pandemic,’ support hotlines are still experiencing an unyielding rise in calls for help, but without necessary aid resources to provide for victims, they have fallen behind in their efforts to respond.

‘Most shelters have closed their doors, leaving women closed in with their abusers and nowhere to go,’ says Tara Cookson, director of feminist research consultancy Ladysmith. ‘If a woman can’t go to her trusted neighbour, or escape to her mother’s house, she’s that much more isolated and that much more at risk.’