A harrowing outcome of the pandemic, not only has Latin America seen some of the highest death rates worldwide, but several countries within the region are now facing considerably worse humanitarian crises than prior to the Coronavirus outbreak.

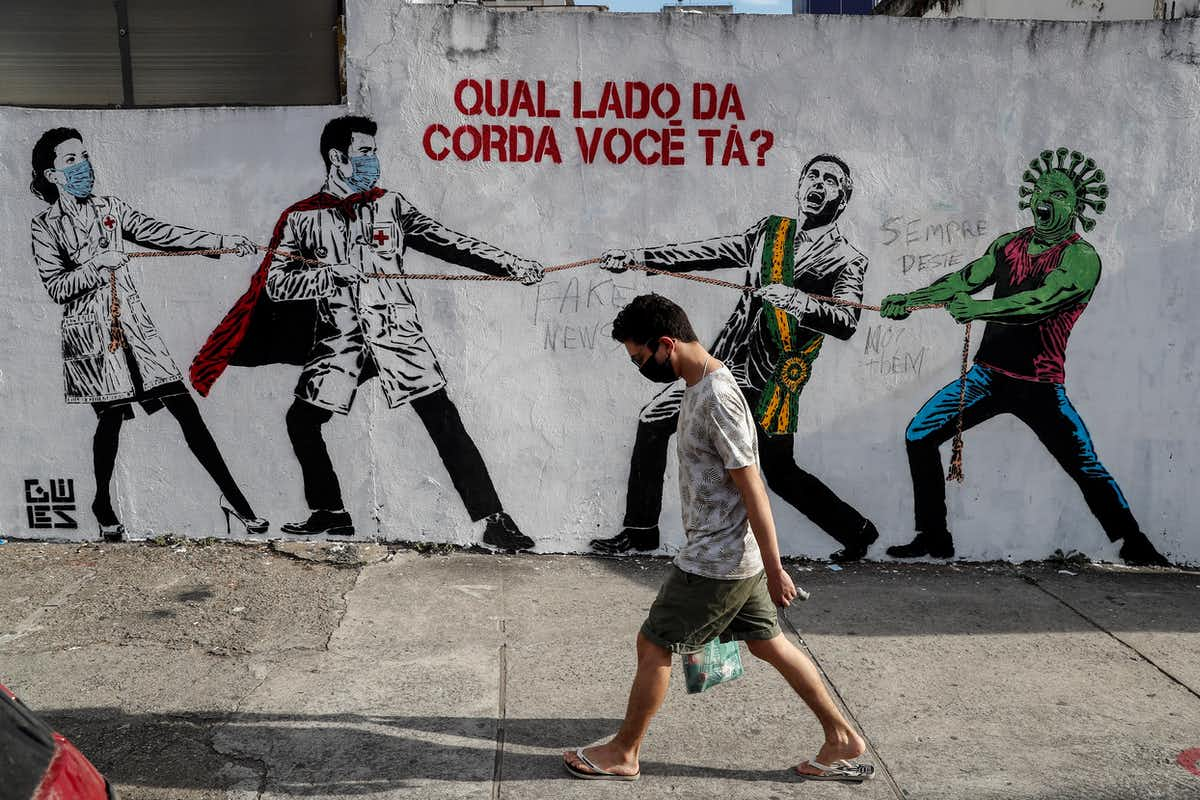

In the nine months following the first reported case of Coronavirus in Latin America, much of the conversation surrounding its impact on the region centred heavily on Brazil, a country with the most virus-related deaths second to the United States. Guaranteed to overwhelm global attention, the staggering mortality rates could be attributed to the errors of Brazil’s hard-right president Jair Bolsonaro, who dismissed Covid-19 as a ‘little flu’ and raged against lockdown measures, declaring self-isolation something ‘for the weak.’

Though his populist handling of the outbreak was indeed cause for international concern, it dominated headlines and left the rest of Latin America out of focus, a region already in turmoil from its struggle to hinder the unrelenting spread of Coronavirus, but one now additionally plagued with humanitarian crises exacerbated tenfold by the pandemic.

‘Borne out of political instability, corruption, social unrest, fragile health systems, and perhaps most importantly, longstanding and pervasive inequality – in income, healthcare, and education – which has been woven into the social and economic fabric of the region’ (The Lancet), Latin America as a whole has long-suffered from a plethora of devastating issues.

However due to the heart-breaking effects of a pandemic that’s left a trail of fatalities in its wake from Mexico to Argentina (400,000 and counting, to be exact), these issues have become significantly latent.

Acting as a smokescreen, Covid-19 has obscured the severe deterioration of crises that were out of control far before anyone began showing symptoms of Coronavirus, and only now is the magnitude of this neglect being realised.

Gender-based violence

Deemed the most lethal location on the planet for women prior to the outbreak, Latin America is as deadly as ever, with activists of the #NiUnaMenos movement blaming Coronavirus for consolidating the ongoing problem of domestic and gendered violence throughout the region.

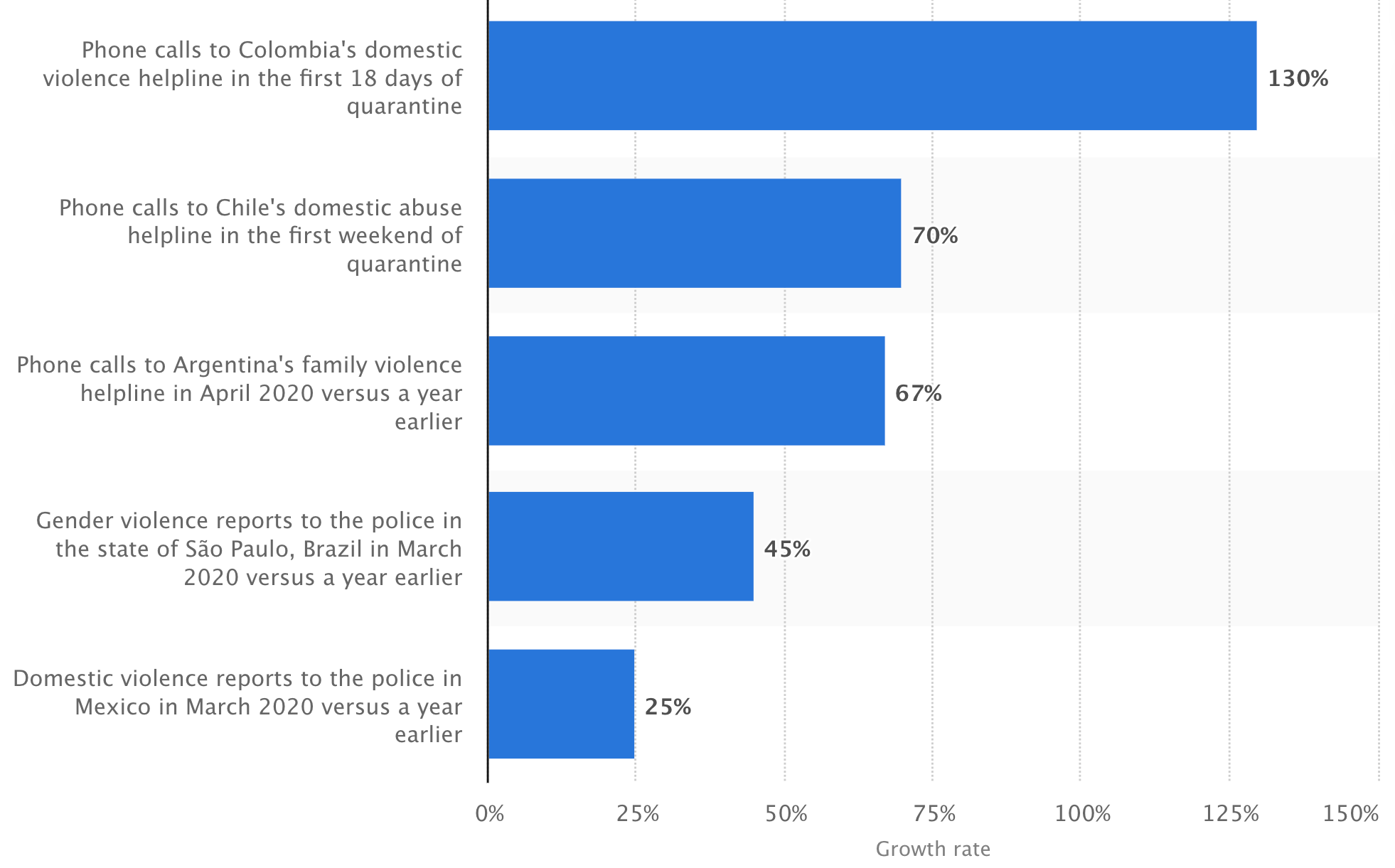

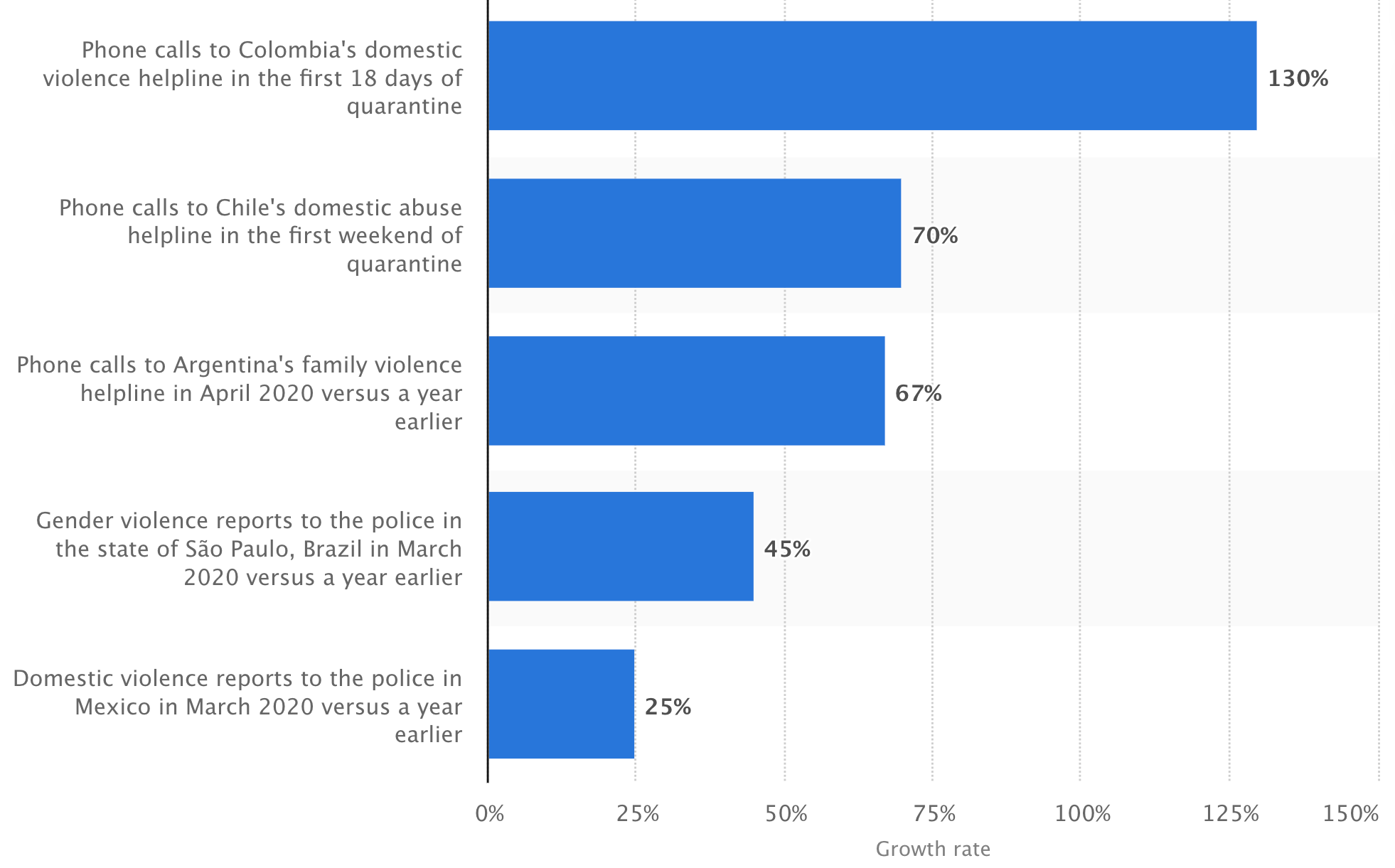

Comprising almost half of the world’s worst offending countries, fears that government-imposed quarantines would put countless women in danger were justified after Colombia alone saw an instantaneous 50% surge in reports of abuse the moment female citizens were instructed to stay indoors.

According to the UN, while an average of twelve Latin American women a day were subject to femicide in 2018, the current reality is much worse, further aggravated by the pandemic which brought about the murder of 18 Argentinian women by their partners in the first 20 days of lockdown, and a 65% increase of corresponding cases in Venezuela.

As this new wave of violence triggered by the unavoidable requirement to isolate continues to hit the region with brute force, campaigners like Arussi Unda, leader of Mexican feminist organisation Brujas del Mar, say that 2020 has catapulted the existing crisis into irrefutable tragedy, with uncertainty posing an added threat.

‘We’re terrified because we don’t know how long this is going to last,’ she says. ‘Women are already in vulnerable positions so it’s even more complicated when their rights – such as the right to move freely – are restricted, in countries where the right to live a life free of violence is not guaranteed.’

Amidst what’s being locally referred to as ‘the other pandemic,’ support hotlines are still experiencing an unyielding rise in calls for help, but without necessary aid resources to provide for victims, they have fallen behind in their efforts to respond. ‘Most shelters have closed their doors, leaving women closed in with their abusers and nowhere to go,’ says Tara Cookson, director of feminist research consultancy Ladysmith. ‘If a woman can’t go to her trusted neighbour, or escape to her mother’s house, she’s that much more isolated and that much more at risk.’

What’s more, despite feeble governmental attempts to address the new territory their countries have been thrust into, those expected to succour given their authority are no better suited to do so than the non-profits they are seemingly reliant on. This is because several Latin American police forces lack even the most basic infrastructure such as the internet to take calls, with one report divulging that 590 officers in Colombia are without access to digital tools.

The disturbing spate of recent cases of violence towards women is conceivably a product of compounding long-term ramifications of the pandemic, primarily the economic fallout that disproportionately affects women. Stripping vulnerable women of financial autonomy, researchers are calling it a regrettable loss of a decade’s work towards gender equality as these women have had no choice but to return to toxic patriarchal spaces dominated by machismo culture.

Of the innumerable horrifying examples of this, one stands out in particular: the account of a woman in Bogotá who contacted a domestic abuse support centre only to later refuse aid on the grounds that she could not leave her home because she was surviving off her husband’s salary. ‘It brings us back to this old dynamic of the man as the provider and the woman who cares for the home,’ adds Cookson.

Jeopardising any former progress at a time when women are in dire need of it, the total shutdown of modern life has unfortunately laid bare what many already knew: that violence against women almost always happens out of society’s field of vision. In Latin America, the sheer absence of a genuine comprehension of the matter, adequate prevention measures, and sufficient attention from policymakers to make visible and consequently tackle such a prevalent issue has done nothing but augment it.

A catastrophe is rapidly unfolding behind the Covid-19 smokescreen and bolstering essential support systems has never been more urgently indispensable.

Widespread displacement

Aggravating structural inequalities that have historically scourged Latin America, the pandemic has additionally exacerbated the already deplorable conditions of migrant, indigenous, and refugee populations throughout the region.

In March, following the implementation of harsh yet crucial restrictions to fight the outbreak, displacement soared, a result of limited access to health and sanitation paired with the heightened levels of job insecurity, overcrowding, and precarious living environments that came with such action.

Overnight, the world transformed into a society of social distancing to avoid an invisible but very present enemy, abandoning those unable to hide and leaving them to face the chaos of migration in which only the strongest survive.

Fleeing this newfound hardship in droves, hundreds and thousands of Latin Americans found themselves trapped at the borders of their own countries, unable to pass through temporary law-enforced closures that immediately froze the legal flow of people. Today, the aforementioned unprecedented pandemic mitigation measures have provoked a rush of what Open Democracy terms ‘a sort of mobility in immobility,’ whereby vulnerable communities must now return en masse – often by foot – to their crises-ridden countries of origin, a vast majority bearing the traumatising burden of their post-lockdown experiences.

‘If things were bad before, now they’re so much worse,’ says Alejandro, whose cousin Juan Carlos was murdered while attempting to escape the ongoing crisis in Venezuela. Left to the mercy of criminal gangs openly combatting for territory when officials at safe border points began turning away hopeless migrants, Alejandro believes Juan Carlos would still be alive if it weren’t for the pandemic. ‘People have all-but-completely stopped crossing because they’re scared of getting killed,’ he says. ‘But with nowhere else to go, it’s the most complex and critical landscape one could imagine.’