Harry Styles’ long-awaited cosmetics brand just dropped a psychedelic-inspired collection. Aesthetic visuals aside, there may exist a wider issue with the way these products are being marketed.

Whether we like it or not, psychedelics are having their moment.

Permeating both mainstream media for their extraordinary medical potential and our social media feeds as young people struggling with mental health conditions increasingly look into them for personal development, hallucinogenic drugs are all the rage in 2022.

That’s in spite of the legal complications that still pervade them, as well as prevailing public stigma surrounding their use.

On this note, with popular culture a direct reflection of the times, it makes sense that the beauty industry would be jumping to conjure the vibes of liberated hippies who spent the 60s exploring new states of consciousness and capitalise on the resurgence of these substances.

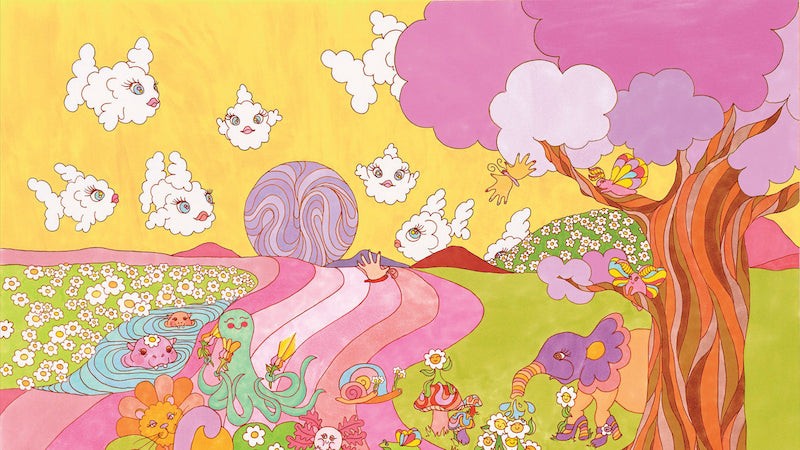

Not for their mind-altering affects per se, rather the rising popularity of the dopamine-inducing, kaleidoscopic visuals we typically associate with LSD, magic mushrooms, and DMT.

Yet, while we’ve already witnessed fashion’s foray into this renaissance with last year’s trippy runways a flurry of bright colours, fantastical prints, and entire collections dedicated to the very compounds themselves (not to mention the 70s obsession of the stylish TikTok generation), beauty’s entry into the world of psychedelia hasn’t been quite so all-consuming.

More a toe dipped in the water than a full-blown dive. Well, until today that is.

Following the CBD craze that’s seen cult skincare and cosmetics companies from eos to Revolution eagerly tap into the hype towards this buzz-worthy ingredient, renowned for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, an assortment of brands have turned their attention to the Class A realm as of late.

In particular, Pleasing by Harry Styles, the singer’s long-awaited beauty venture, which just dropped Shroom Bloom, an aptly titled variety of psych-inspired products advertised to us through our screens with images reminiscent of The Beatle’s iconic Yellow Submarine video.

These include a ‘Lucid’ Overnight Serum labelled ‘Acid Drops,’ the undeniably provocative colloquialism of which has prompted many to question the industry’s role in glamourising and potentially trivialising recreational drug culture with its marketing.

Namely due to Styles’ primarily underaged fanbase, amassed during his 1D days and now coveters of his quick-to-sell-out range of nail polishes.

However, Styles isn’t the only one in the firing line, with Estée Laundry – the anonymous Instagram collective that’s been holding beauty to account since 2018 – having recently called out Milk Makeup for ‘weedwashing.’

Essentially, in an effort to push its ‘Kush’ lip balms, ‘puff puff brush’ mascaras, and ‘hiiigh volume’ brow gels, the company had started selling paraphernalia like clear plastic dime baggies printed with the numbers 4:20 and stamps in the shape of cannabis leaves for consumers to display proudly on their skin.

It’s somewhat unsurprising therefore that this raised a few eyebrows, arguably more problematic and far-reaching than Styles’ playful approach, but nowhere near as callous as Svenja Walberg’s 2019 ‘Lash Cocaine’ (which speaks for itself, really).

‘Youth culture and drug sub-culture have had shared roots in language and popular slang since the 60s, but it isn’t until recently that this slang has made it onto the shelves of commercial retailers,’ says Alexia Inge of Cult Beauty.

‘To differentiate amongst an abundance of new brands, marketeers will grab at anything that attracts free attention and will rinse the trend until it no longer works!’