Realising Nikola Tesla’s 1930s theory that the Earth could one day act as a super battery, a team of engineers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have successfully generated hygroelectricity.

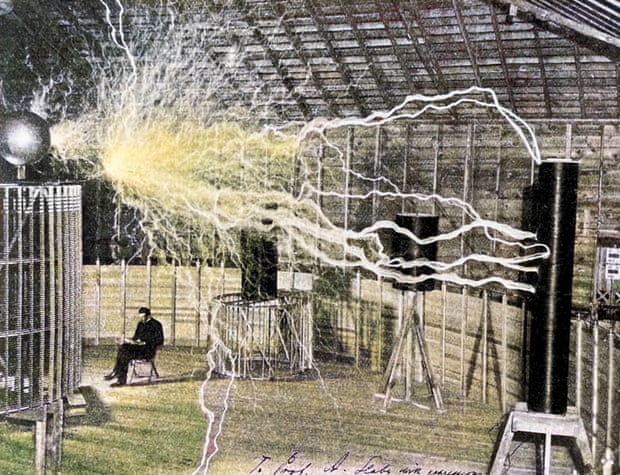

‘We are on the threshold of a gigantic revolution, based on the wireless transmission of power,’ wrote Nikola Tesla in the 1930s.

‘We will be enabled to illuminate the whole sky at night and eventually we will flash power in virtually unlimited amounts to other planets.’

The Serbian-American inventor, who is best known for his contributions to the design of the modern alternating current electricity supply system, was – almost a century ago – theorising that the Earth could one day act as a super battery.

Today, that theory has been realised by a team of engineers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who have successfully generated a small but continuous amount of renewable energy from humidity in the air.

‘To be frank, it was an accident,’ the study’s lead author, Professor Jun Yao, told the Guardian.

‘We were actually interested in making a simple sensor for humidity in the air, but for whatever reason, the student who was working on that forgot to plug in the power.’

Despite this, says Yao, the device (which comprised an array of microscopic tubes called nanowires) emitted an electrical signal.

Explaining this further, Yao tells us to think of a cloud, which is nothing more than a mass of water droplets, each containing a charge that produces a lightning bolt when conditions are right.

Because the individual nanowires are less than one-thousandth the diameter of a human hair, wide enough that an airborne water molecule can enter, but so narrow it bumps around, a single bump is capable of lending the material a charge that, with increased frequency, flows through a positive and negative pull at opposite ends of the tube.

‘What we’ve done is create a human-built, small-scale cloud that produces electricity for us predictably and continuously so that we can harvest it. It’s really like a battery,’ says Yao, referencing Tesla’s suggestion that we view the Earth and upper atmosphere as a viable source of clean, pollution-free hygroelectricity.