As if they weren’t magical enough, scientists have discovered that mushrooms are potentially talking to each other using a bountiful vocabulary which bears a striking structural similarity to human speech.

If you aren’t a stranger to my writing, by now I’m sure you’re well aware of my deep-rooted obsession with all thing’s mycelium, my fascination towards which recently peaked after seeing the incredible Fantastic Fungi documentary on Netflix (certainly give it a watch if you haven’t already).

Of the many eye-opening facts that were brought to my attention during this viewing, one stood out to me in particular: that of fungi’s ability to communicate.

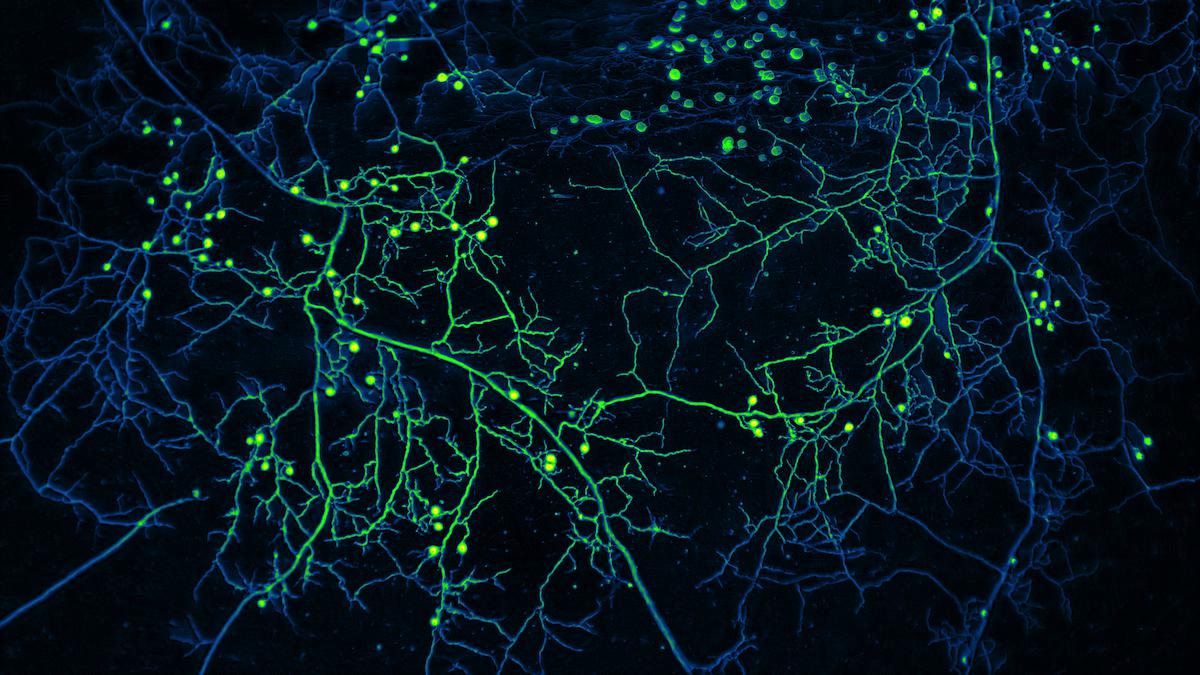

According to renowned mycologist Paul Stamets, they do so through chemical signals delivered along an underground network so vast there are 300 miles of these branches – which share the same design as the world wide web if you’re needing a mental image – beneath every single step we take.

It gets better, however, because as if they weren’t magical enough, scientists have just discovered that not only are mushrooms able to interact, but that they may be talking to each other using a bountiful vocabulary of up to 50 ‘words’ which bear a striking structural similarity to human speech.

This might come as a surprise, given that fungi are the most common species on Earth. If they were anything other than silent, relatively self-contained organisms, you’d assume we wouldn’t even hear ourselves think.

The finding makes a great deal of sense on the back of previous research which proved them to be ‘speaking’ in order to share information about food or injury with distant parts of themselves. It’s also how they explore their surroundings, tip off fellow fungi to potential threats, and make their presence known to other members of their cluster, much like wolves howling to alert the pack.