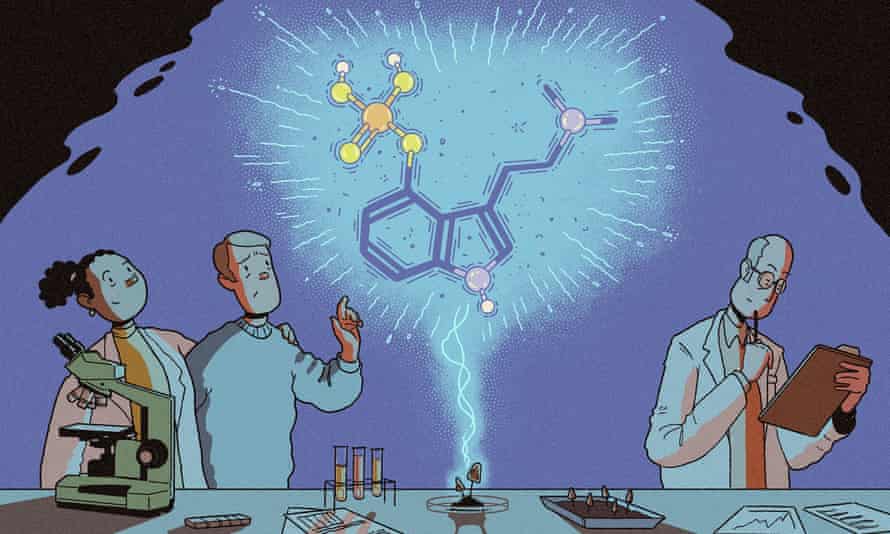

Could psychedelics transform mental health? A growing number of scientists have begun asking whether mind-altering drugs such as DMT, magic mushrooms, and LSD may also have the potential to help treat anxiety, addiction, and depression.

In the first study of its kind, UK regulators have given dimethyltriptamine (DMT) the green light for clinical trial into its effectiveness in treating patients with depression. Known for inducing powerful trips, the hallucinogenic is proving increasingly popular as a means of getting to the root cause of mental illnesses rather than simply dampening symptoms.

Though the Home Office must yet give permission for the trial to go ahead, the MHRA’s approval is a revolutionary step towards changing minds about the potential of ‘once stigmatised compounds’ as useful medical therapies.

‘This is a truly ground-breaking moment in the race to effectively and safely treat depression,’ says Dr Carol Routledge, chief medical and scientific officer at Small Pharma. ‘By adopting responsible evidence-based research and development into psychedelic medicine, we hope to help rebrand these drugs and integrate them into current healthcare systems.’

It’s not the first time experts have acknowledged the extraordinary medical potential of psychedelic drugs in recent years. In January, a study uncovered that a single dose of psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms) can significantly reduce stress and anxiety in cancer patients, sometimes for as long as half a decade following administration. And in 2019, Johns Hopkins – a world-renowned research university – launched the first-ever centre devoted exclusively to researching psychedelics in the US.

Receiving the go ahead from policymakers has been nothing short of an immense struggle, however. When mind-altering substances came to scientific attention in the 50s, any studies taking place at the time came to a sudden halt as recreational use of the drugs sparked controversy – leaving scientists stuck in the preliminary stages of research.

Subsequently, any existing support for such studies faded when the federal government listed them as Schedule 1 drugs in the 70s, again amid safety concerns. This is despite the fact that psychologists and psychiatrists have been studying hallucinogenics since the earliest days of their discovery.

Fortunately, beliefs are being revisited and legislators have begun to understand the value of funding these projects. Particularly because psychedelics demonstrate genuine promise in alleviating some of the hardest (and most expensive) conditions – addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder, and end-of-life anxiety, among many others – to treat.

‘These are among the most incapacitating and costly disorders known to humankind,’ says Matthew Johnson, one of the researchers at Johns Hopkins. ‘We have some things that help, but for some people they’re barely scratching the surface, [and] for some people there’s nothing that helps at all.’

At present, society is experiencing an acute mental health crisis, exacerbated tenfold by a pandemic that’s dramatically intensified feelings of loneliness, uncertainty, and grief. In the US, there’s been a 20% spike in the number of prescriptions for antidepressants and in the UK, where an estimated seven million adults are taking them, demand is threatening to exceed supply.

With the global antidepressant market bursting at the seams and nowhere near enough support systems in place to guide patients in the right direction, never before has there been a more pivotal moment to introduce psychedelics into mainstream medicine.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6705191/depression.0.gif)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6705295/your_brain_on_LSD_2.0.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3902402/shutterstock_63002920.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6705171/life.0.gif)