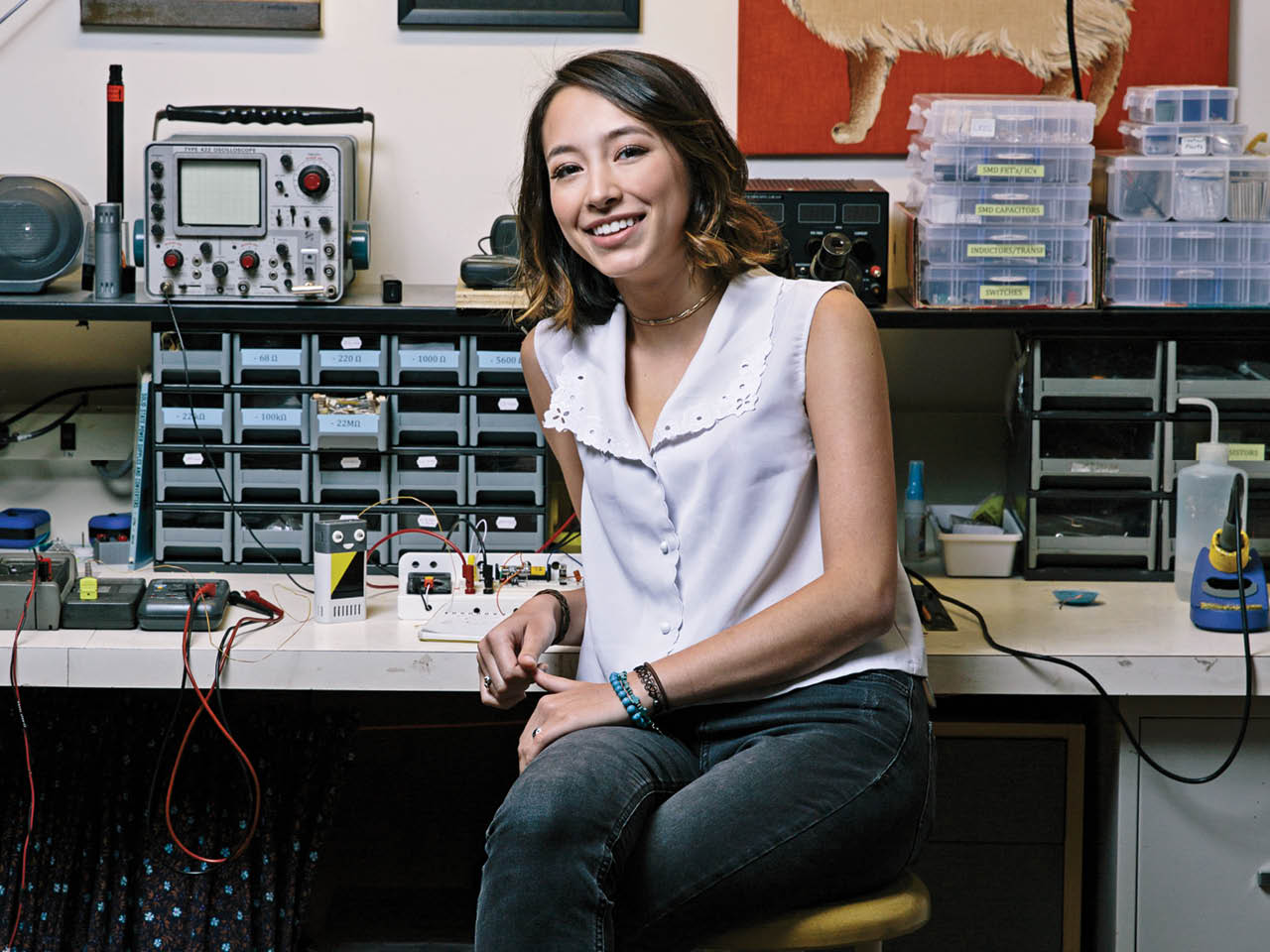

Ann Makosinski is innovative, entrepreneurial, and eager to build a better planet – all traits of a multitalented Gen Zer who’s striving to prove that science and art go hand in hand.

Canadian inventor Ann Makosinski had something of an unusual childhood.

Daughter of a father born in Poland during WW2 and mother from a tiny town in the Philippines, she recalls their parenting style as ‘unique,’ guided by a shared mentality of growing up with less.

‘The first thing they ever gave me was a box of transistors and other electronic parts,’ she tells me. ‘If I wanted access to toys I’d have to get creative, find ways of entertaining myself.’

This, she most certainly did. At just five years old, Makosinski would use a hot glue gun to meld together spare items and garbage from around the house, proving that necessity is indeed the architect of invention.

‘This notion of gathering the resources around me and piecing them together to make something better came quite naturally,’ she explains. ‘It was out of necessity.’

Believing our brains are programmed to react creatively to need, Makosinski is a shining example of how Gen Z can be creative with the resources around us.

She associates this early realisation with her present day motivations, alongside an ingrained message from her parents that ‘time learning anything substantial is time well used.’

‘One of the most important things [they] taught me was not to waste my time,’ she says. ‘So every day I ask myself, how can I spend it efficiently and effectively?’

Evidently, Makosinski’s unrelenting work ethic and ability to come up with unique solutions has been there from day one.

Few are pointed in this direction at such a young age, mind, and she stresses that anyone looking up to her should recognise that she is just a ‘normal’ (yet innately curious) girl ‘who used her time differently after school.’

‘I want – especially kids – to feel as though they can invent their own solutions rather than waiting for other people to make them,’ she says.

‘I don’t think marketing me as a “child prodigy” is accurate at all, the term suggests un-attainability and the whole point of what I do is in the hope that anyone watching will see they’re also very capable. You don’t have to be a genius to make a difference.’

Makosinski’s humility is admirable to say the least given that, throughout the last decade, her penchant for tinkering definitely hasn’t gone unnoticed.

In 2013, she won the Google Science Fair with a flashlight that uses Peltier tiles to transform human thermal energy – a natural by-product of everyday life – from the palm of the hand into a battery-free source of light.

The device, she explains, is in the realm of ‘alternative energy harvesting’ – the kind that’s all around us but that we don’t often take advantage of.

‘One of the main problems we have right now is this lack of energy,’ she says, acutely aware she has an opportunity to highlight a requirement for fossil fuel replacements.

‘I think looking at natural ways to harvest it is the future, rather than continuing to pollute the Earth with more and more carbon emissions.’

However, it isn’t solely her inquisitive mind and clever adaptation of technology that wows me (so far she has two energy-efficient gadgets under her belt), it’s her inspiration behind it: the plight of a friend in the Philippines who failed a grade at school because she had no electricity to study with at night.

Going forward, Makosinski hopes to partner with NGOs to bring her brainchildren to poorer, electricity-deprived populations around the globe.

This empathy-driven ingenuity and keen sense for problem solving is what has garnered her a barrage of praise-heavy media coverage, numerous awards, and the attention of Time Magazine and Forbes Magazine, both of which named her one of their 30 people under 30 who are changing the world.

Interestingly, she’s doing so in ways that are equally as impressive as her inventions which, albeit remarkable, are not the only thing Makosinski’s focusing on these days.

Exemplifying the qualities of her industrious generation – innovative, entrepreneurial, and eager to build a better planet (among many others) – she’s on a mission to prove that science and art go hand in hand.

Contrary to popular belief which has long implied that pursuing them simultaneously is something of an overly ambitious dream, Makosinski is here to show her peers that the best ideas derive from merging the two.

‘Traditionally art has always been viewed as a hobby and science a career, but I think it’s really important to emphasise teaching them side by side,’ she tells me.

‘Growing up with this combination shaped me into who I am today and what I’m interested in.’

Makosinski practices this duality in her own life through exploring her creative side as an English Literature student while pursuing her passion for science through the development of her inventions. This balance, she says, leads to more imaginative projects.

‘We should be bringing arts and design into science and creating STEAM,’ she says. ‘If you think about it, a lot of the great scientists were also great artists.’

Makosinski is also a strong advocate of the creative process, and firmly believes that we as a society must do what we can to foster the creativity of a burgeoning generation of innovators.

‘The combination of critical thinking that’s unique to you, as well as being able to communicate your ideas are the top two things that all educational systems need to start implementing from early on, instead of teaching only basic subjects,’ she says, looking to encourage the youth of today to home in on their independent thinking and use it to excel, particularly girls who, until now, have been relatively hard pressed to make a dent in Makosinski’s sphere.

‘I think it’s really important when we showcase women doing tech and creative work as all-rounded people with other interests outside of science,’ she says.