In the first large-scale study of its kind, researchers have found that microbes living in oceans and soils around the world have learned to eat at least ten different types of plastic.

Plastic is by far the world’s biggest issue when it comes to pollution.

Most types are notoriously hard to recycle and even single-use plastics can remain in-tact for 500 years once thrown out.

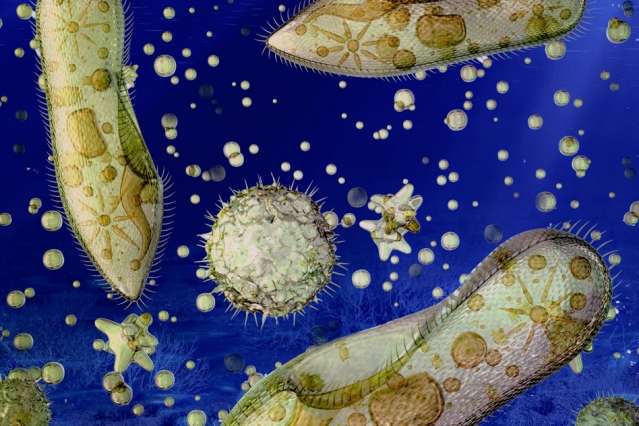

Although human led clean-up efforts are commendable, they’re no match for hard-to-reach areas like mountain peaks and the deep sea. So wouldn’t it be splendid if some creature in the natural world adapted to munch on plastic once it got hungry?

Well, a new discovery suggests this could very well be the case – sort of.

By scanning 200 million genes found in DNA samples taken from oceans and soils around the world, researchers discovered 30,000 different enzymes that are capable of degrading plastic.

That’s right – at least 1 in 4 bacterial microbes carried enzymes that had potential to break down plastic materials. The enzymes present were unique to the type of plastic pollution in the microbe’s environment, leading scientists to conclude the bacteria had adapted to ‘eat’ the pollution.