The ecological artist has created a robotic plant that grows based on biodiversity data from the Natural History Museum. It demonstrates how the choices we make now will affect the state of nature over the next thirty years. We spoke with him about his mission to turn facts into feelings.

Thijs Biersteker is an award-winning ecological artist whose work channels creativity into raising awareness about pressing environmental issues.

His immersive instillations, which are based on collaborations with the world’s top scientists and institutions, convert hard-hitting climate change data into a tangible experience that, as he likes to put it, ‘turns facts into feelings.’

Through this symbiosis between viewers and research around topics like the collapse of our ecosystem, he’s actively fostering empowerment.

This, he hopes, will translate into greater action as we confront the challenges ahead.

‘If the research does not reach us, then how can the research teach us,’ reads Thijs’ about page.

When asked what brought him to this conclusion and why he’s dedicating his life to making the ‘invisible impact we have on the planet visible,’ however, he tells me that his journey is not important, rather his mission’s.

Dissatisfied with the inherent lack of accessible, understandable, and relatable information available regarding the biodiversity crisis and its urgency, Thijs is striving to make knowledge more comprehensible so we as individuals can connect with our emotions and use them to have a lasting effect.

‘Frustration is my inspiration,’ he says. ‘I use my feelings towards the state of the world as one of my drivers. Facts alone don’t bring about purposeful action but combined with accessibility they can.’

Of the long list of Thijs’ projects to date, his latest undertaking is arguably the best example of this.

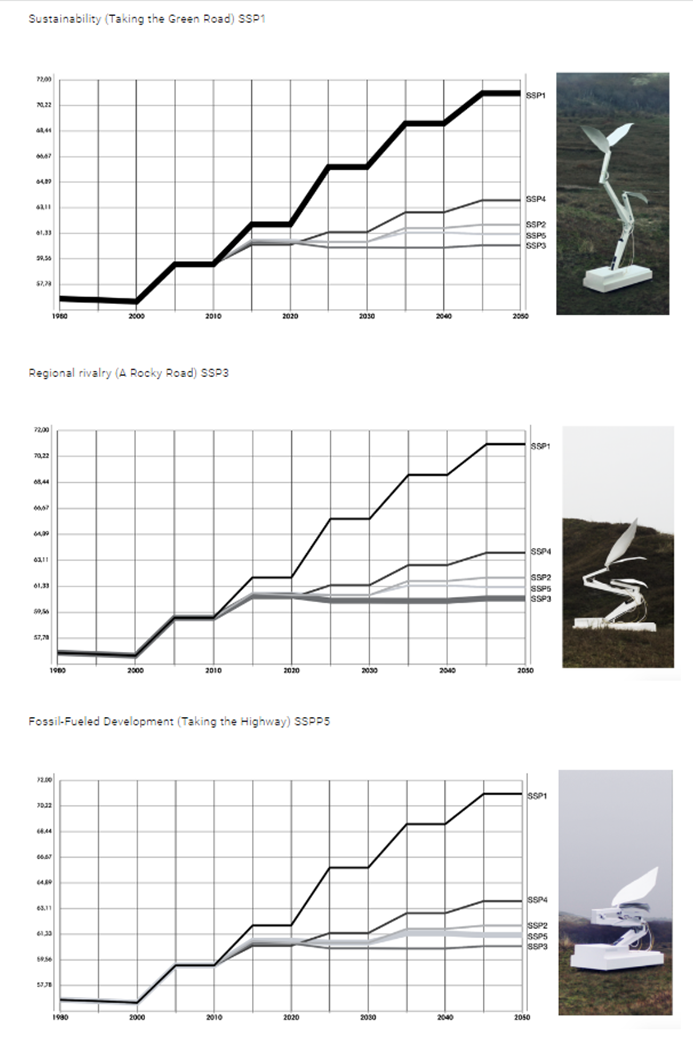

In partnership with the Natural History Museum (NHM), he’s crafted a 5-metre-tall robotic plant that grows on biodiversity data to demonstrate how the choices we are making now will affect the state of nature over the next thirty years.

The data is being drawn from the NHM’s Biodiversity Intactness Index (BII), which is a measure of how much of an area’s natural biodiversity remains. It ranges from 100% (an intact ecosystem absent of any human footprint) to 0% (a region with biodiversity derived entirely from external sources).

‘There’s a so-called planetary boundary – a suggested safe limit – whereby if the BII falls below 90% then ecological systems can’t be relied on to give us what we need and we’ll have to work harder to reap the same benefits,’ says Professor Andy Purvis, one of the NHM researchers involved in the endeavour.

‘My team at the NHM models how the BII has changed and how it might change under alternative futures.’

Set to take centre stage at COP15, ‘Econario’ (as it’s called) will provide a detailed forecast each day, flourishing or wilting in response to the decisions taken at this major summit.

‘For me, this work and this location coming together is the perfect fit,’ says Thijs.

‘Econario is engineered like a thermal meter for biodiversity and COP15 presents an opportunity for us to discuss the essence of life on Earth and how we handle it.’

As Andy explains, Econario seeks to communicate data in a way that’s more visceral, genuine, and emotional than how it’s usually conveyed by scientists.

In his opinion, while statistics that are the focus of negotiations like those taking place at COP15 are summarising things that matter, in most cases they’re ‘dry’ and ‘divorced from emotion.’

‘I love how Econario bridges this gap,’ he says.

‘When it’s doing its interpretive dance around a future where nature recovers and is nurtured, you cheer for it. Conversely, when it’s responding to a future where we don’t get our act together, it’s like a punch to the gut. This is deeply moving because if we don’t take these challenges seriously enough, it’ll be much worse than a punch to the gut.’

Noting how Econario encourages people to accept that abstract statistics do have meaning, Andy anticipates that this will make the scale of biodiversity loss – and the threat it poses to our existence – more universally acknowledged.

Especially among inhabitants of the Global North, for whom the crisis is frequently deemed too ‘far away’ to be of concern.

‘It’s about a lot more than just the extinction of rare species in remote corners of the globe,’ he says.

‘We’re looking at the diminution of nature everywhere, nature we depend on to survive. Without action, it’s going to impact absolutely everybody’s day-to-day.’

At a time when we find ourselves more distanced than ever before from the natural world – and more wrapped up in the digital one – this kind of pioneering initiative is invaluable.

Not only does Econario merge the two in a way that’s appealing both intellectually and technologically, but it brings the reality of the upcoming solution-based discussions to life.

‘I believe that standing across from something physical is always a stronger experience than doing something in the digital world,’ says Thijs.

‘It’s a perfect representation of the time we’re in and the amount of emotion that’s provoked when you watch our sophisticated motors mimic the growth of a fragile seed is extraordinary.’

In doing so, people in power will have no other option but to put their money where their mouths are, or risk being held accountable for their apathy.