The UN conference aims to lay out a plan to tackle the ‘unsustainable rate’ of global biodiversity loss that’s ranked as one of the biggest threats facing humanity. Here’s all you need to know.

This week, scientists, rights advocates, and delegates from 190-odd nations are gathering in Canada to tackle one of the world’s most pressing environmental issues: the loss of biodiversity and what can be done to reverse it.

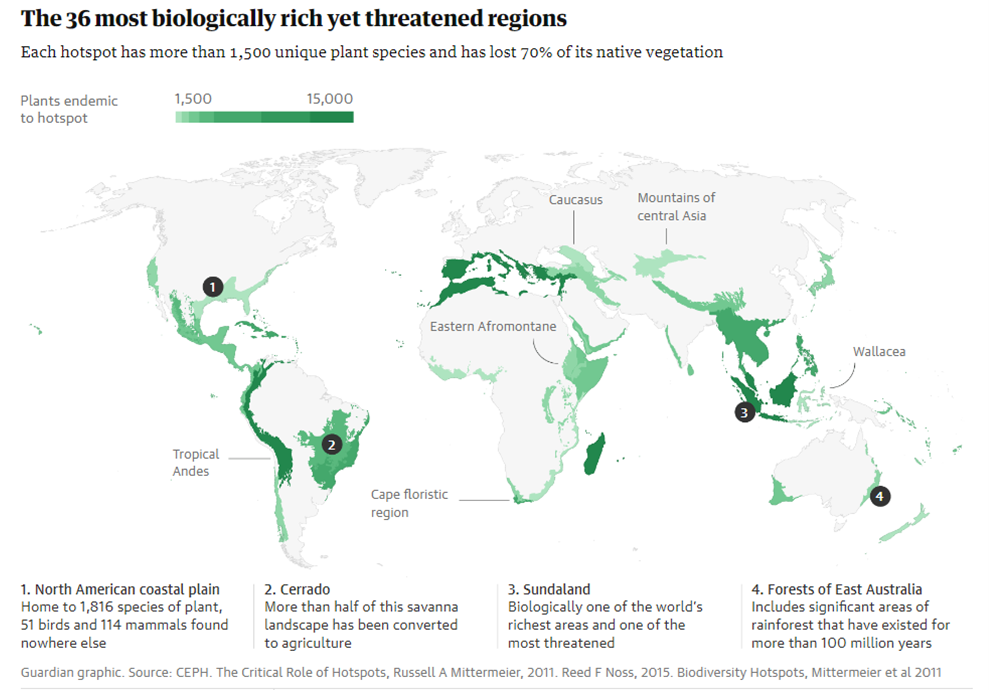

It comes after years of warnings that climate change is leading to an ‘unprecedented’ decline in animals, plants, and other species, and threatening various ecosystems.

‘It may be one of the most important meetings humanity has ever had,’ says Alexandre Antonelli, Kew Gardens’ director of science.

‘We have a very narrow window of opportunity to halt the loss of biodiversity by 2030 and reverse its decline by 2050; we may never have that chance again.’

What is COP15?

Also known as the United Nations Biodiversity Conference, COP15 is the fifteenth meeting of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), rallying countries to agree on targets to guarantee the survival of species and curb the collapse of flora and fauna across the globe.

Due to the pandemic, these nations have not met for several years, so it’s a particularly momentous once-in-a-generation opportunity to slow down the ongoing destruction of the natural world.

Previous aims, agreed at COP10 in Japan, have still not been met, meaning there’s renewed pressure to enforce the financial and political support necessary to confront this crisis.

To the leaders and decision makers attending #COP15, the @UNBiodiversity Conference: the world is watching.

Nature is in crisis – we must capitalize on this unmissable opportunity to reverse nature loss by 2030.

RT to let world leaders know that all eyes are on them. #TeamEarth pic.twitter.com/GW6Zv1F0cQ— WWF (@WWF) December 2, 2022

While biodiversity and climate change are inextricably linked and must be addressed in unison, COP15 will focus on strategies to halt biodiversity loss. This is how it differs from COP27, which centred on amplifying efforts to limit global warming and mitigate ecological breakdown.

From tomorrow, governments will sign off targets under the three objectives of the CBD: to conserve biological diversity, to use its components sustainably, and to provide fair and equitable access to the benefits of using genetic resources. The summit’s final text – known as the post-2020 global biodiversity framework – is likely to include more than 20 legally binding pledges and rules.

‘We can no longer continue with a ‘business as usual’ attitude,’ said Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, executive secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. She is urging states to adopt an ‘ambitious, realistic and implementable’ plan that won’t – yet again – fail on every count.

Why is it important?

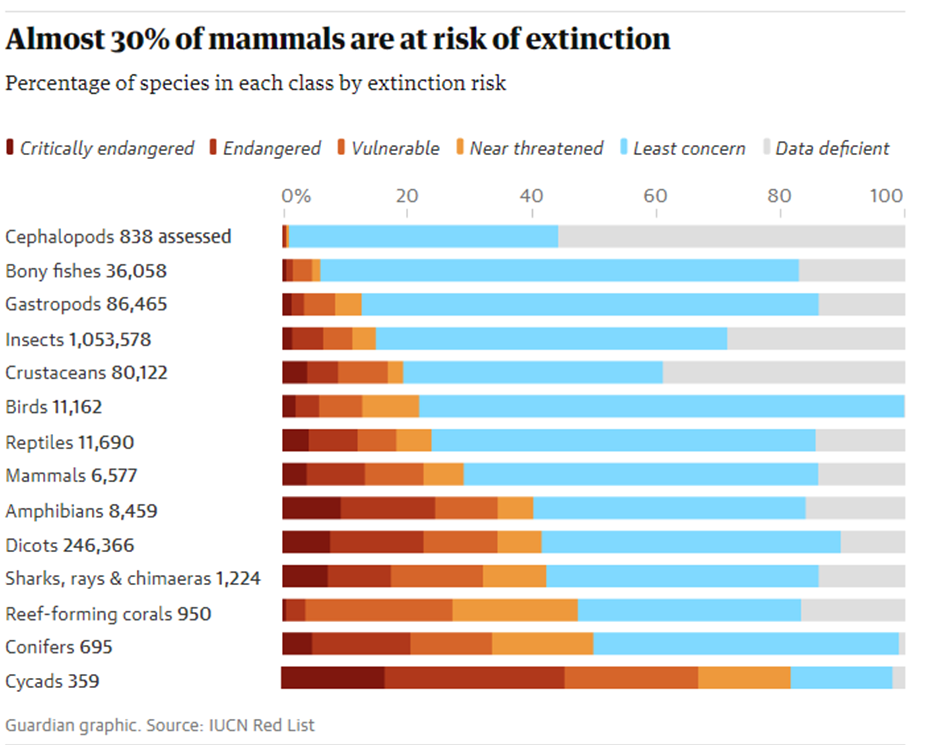

According to scientists, the Earth is currently enduring the largest loss of life since the time of the dinosaurs, which threatens the foundations of human civilisation as we know it.

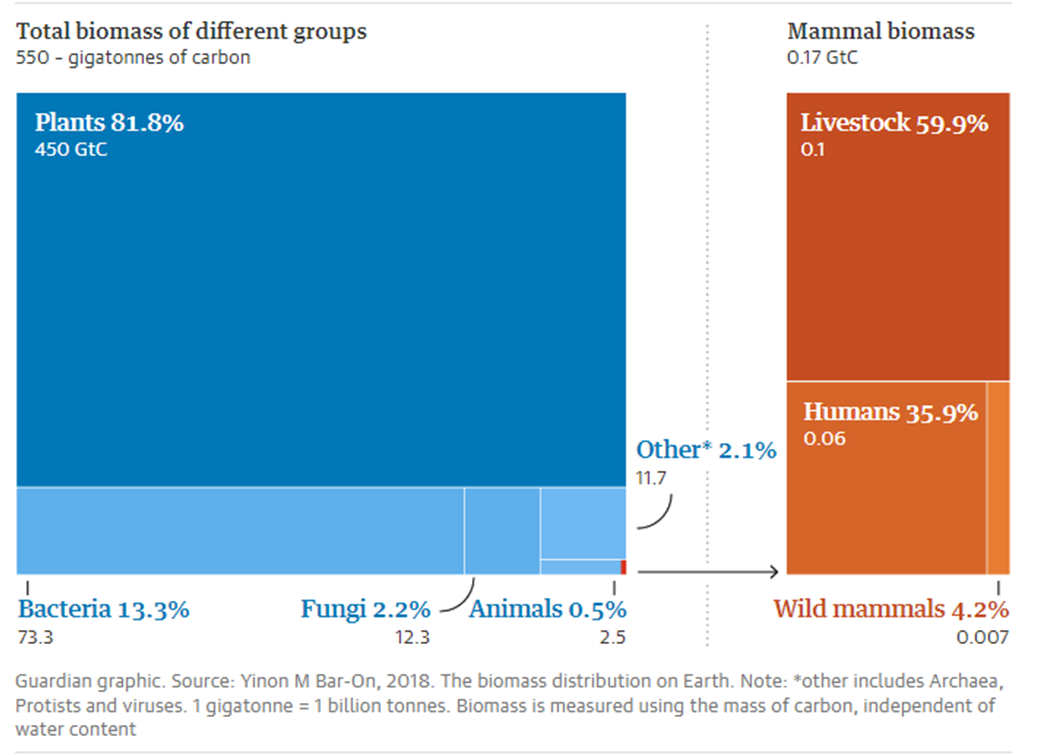

This is because all the interactions between animals, plants, fungi, and even microorganisms like bacteria lead to the food we eat and the medicines we rely on.

They also underpin our health and wellbeing, ensuring we have clean water and oxygen.

Not to mention that plants and fungi regulate the climate, protect communities from natural disasters like hurricane damage, and counteract the pollution in the air by carbon-sequestering.

Ironically, however, it’s human behaviour that’s driving this ‘sixth mass extinction,’ namely how we farm, pollute, drive, heat our homes, and consume beyond what our planet is capable of providing.

To put into perspective the extent of the issue, a recent report revealed that there’s been a 69% plunge in wildlife populations over the past 48 years.

Additionally, in 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services estimated that three-quarters of the world’s land surface and 66% of its oceans had been significantly altered by our existence.