According to a leading scientific assessment warning that humanity is ‘losing the war’ to save nature, wild species populations have shrunk on average by 69 per cent since the 1970s.

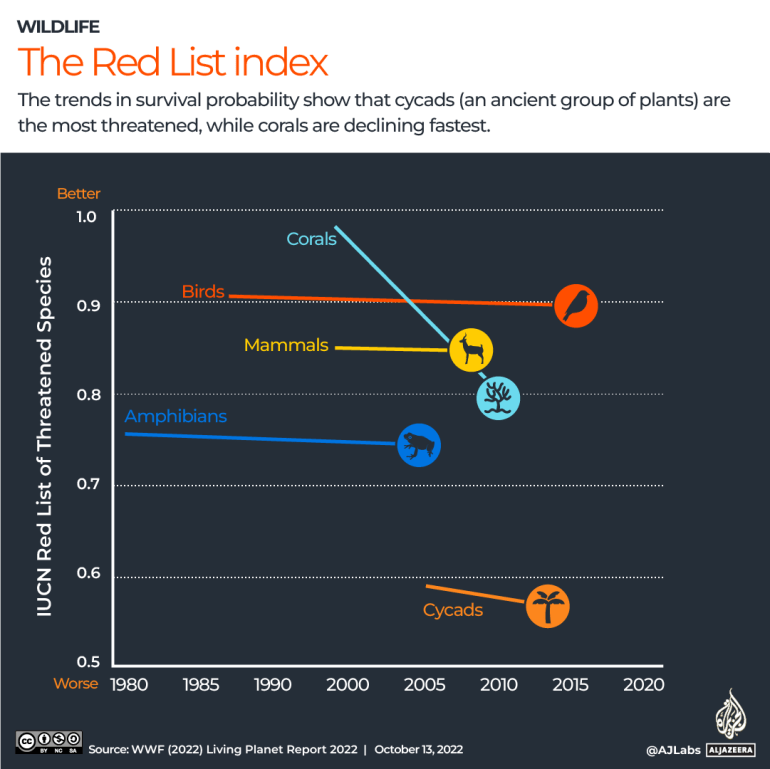

A bleak new report from WWF in collaboration with the Zoological Society London on biodiversity loss has revealed that the abundance of wild mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish is in freefall – shrinking 69 per cent on average between 1970 and 2018.

Two years ago, the figure stood at 68 per cent, four years ago, it was at 60 per cent.

‘Nature is unravelling and the natural world is emptying,’ says Andrew Terry, director of conservation and policy at ZSL.

‘The index highlights how we have cut away the very foundation of life and the situation continues to worsen.’

The finding is a result of examining how 32,000 populations of more than 5,000 species around the Earth are faring by measuring their growth or decline.

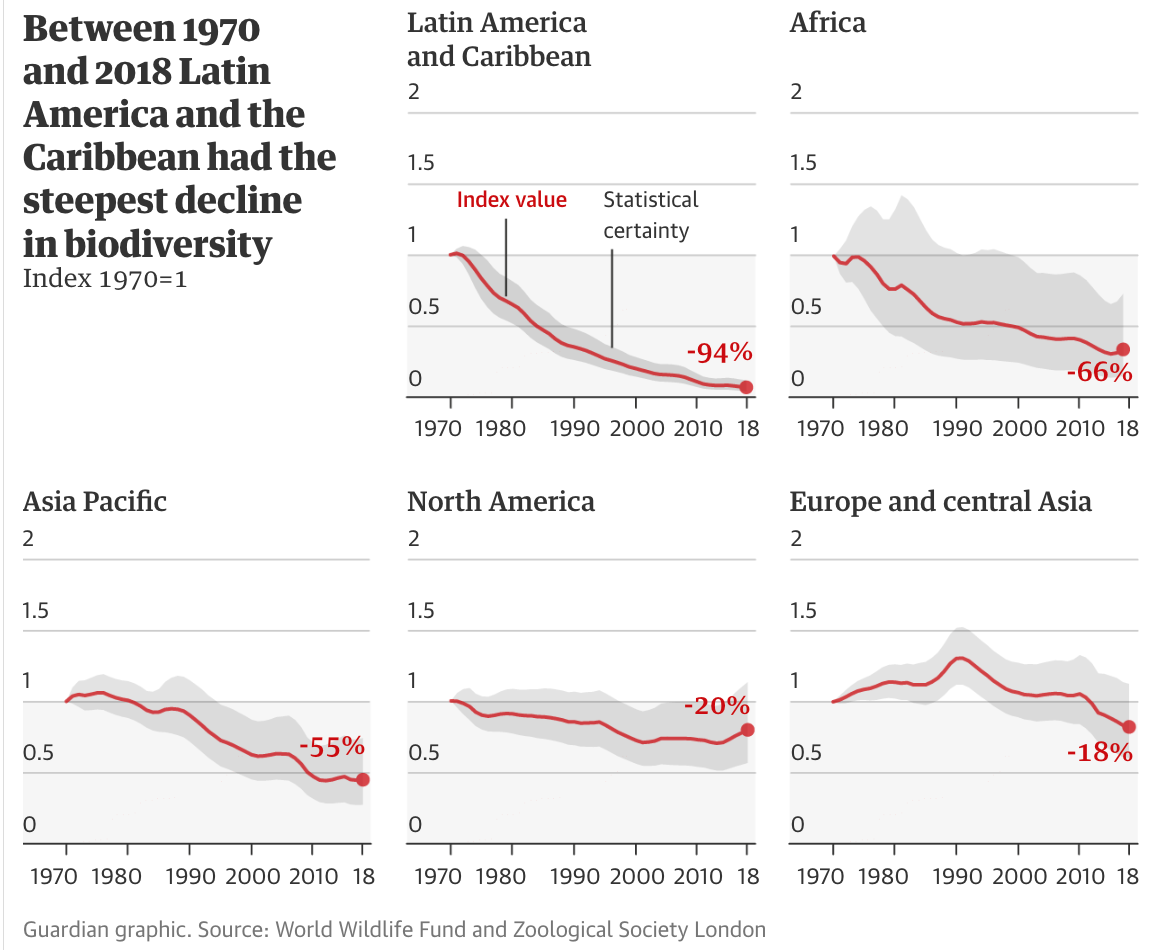

Those in Latin America and the Caribbean have been hit especially hard, experiencing a steep 94 per cent drop in just 50 years, followed by Africa at 66 per cent, Asia and the Pacific at 55 per cent, North America at 20 per cent, and Europe at 18 per cent.

The total loss is akin to the human population of Europe, the Americas, Africa, Oceania and China disappearing.

Future declines are not inevitable, say the authors, who pinpoint the Himalayas, south-east Asia, the east coast of Australia, and the Amazon basin among priority areas.

‘Despite the science, the catastrophic projections, the impassioned speeches and promises, the burning forests, submerged countries, record temperatures and displaced millions, world leaders continue to sit back and watch our world burn in front of our eyes,’ says Tanya Steele, chief executive at WWF UK.

‘The climate and nature crises, their fates entwined, are not some faraway threat our grandchildren will solve with still-to-be-discovered technology.’

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24009513/P1bP0_the_demand_for_more_meat_is_the_leading_cause_of_deforestation__5_.png)