New research has identified that two vapes are thrown away every second in the UK alone, ending up in landfill despite the fact they contain lithium, a valuable and increasingly scarce metal on which much of the high-tech economy depends.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ll know that vapes are all the rage.

Replacing one of the leading cause of preventable death worldwide, the small, brightly-coloured, single-use devices are, quite literally, everywhere.

So much so, in fact, that it’s become far more common to smell berry-scented vape air in any major city than it is to cough on cigarette smoke.

Often seen in the hands of young people due to their affordability, the popularity of flavoursome aesthetically-pleasing vapes has far surpassed that of cigarettes.

This is confirmed by several recent studies, one of which found the number of British smokers to have dropped below 15 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 compared with a dramatic uptick in vaping from one to 57 per cent during 2021.

Yet surprisingly, fairly little remains understood when it comes to the health implications of inhaling vapes on a regular basis.

That’s despite ongoing murmurs of ‘popcorn lungs’ and talk that the EU is proposing a total ban on the sale of such products as part of its plan to fight cancer.

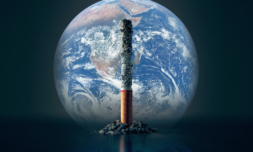

What is known, however, is that the seemingly unending boom in sales is having a detrimental impact on not only our planet, but our resources as well.

With two disposable vapes needlessly discarded every second in the UK alone and either ending up on landfill or being sent to incinerators, some ten tonnes of lithium – a valuable and increasingly scarce metal – is being wasted annually.

To put that into perspective, that amount is enough to build 1,200 car batteries which we’ll be needing if we’re to power the electric vehicles of the future.

And you thought the tobacco industry’s ecological impact was devastating.

‘We can’t be throwing these materials away, it really is madness in a climate emergency,’ says Mark Miodownik, professor of materials and society at University College London.

‘It’s in your laptop, it’s in your mobile phone, it’s in electric cars. This is the material that we are absolutely relying on to shift away from fossil fuels and address climate issues.’