The oppressing weight of the system doesn’t only crush us from above; by consenting to damaging racial narratives, we prop it up.

As race riots continue to rip open the heart of the country that was meant to guide us in principles of freedom, a courtroom in Hennepin County District Court, Minnesota, stands unexpectedly empty. It was meant to play host to the first court appearance of ex-police officer Derek Chauvin this Monday. Chauvin has been charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter after kneeling on the neck of black man George Floyd until he died. The court date has now been pushed back to 8th June, as officials ironically fear for Chauvin’s life in the midst of the civil unrest his actions ignited.

One can imagine that Chauvin, currently on suicide watch at a maximum-security prison, is feeling pretty hard done by. After all, what he did was nothing new. Many white colleagues of his in the Minneapolis Police Department have killed black people in the line of duty and faced no consequences. Each year between 900 and 1000 people are shot and killed by police in the US, most of them black or hispanic, but US police officers rarely get charged, and convictions are almost unheard of. He is free from precedent, so why is he not free absolutely?

Unfortunately for Chauvin, his act of deadly police brutality was one of the few that is recorded and disseminated, instead of the countless acts that go unseen.

I use the word countless quite literally, because there’s no good official data on how many homicides police commit each year. The US federal government tracks fatal injuries resulting from police action through two databases: the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR), and the Bureau of Justice Statistics Arrest-Related Deaths (ARD). But A 2015 study found that from 2003 to 2009 and 2011, both systems let deaths fall through the cracks. More than one-quarter (28%) of police-caused deaths weren’t tracked at all under ARD or SHR.

Of the 72% of police killings that are on average recorded, the vast majority are written off as ‘justified’. What constitutes justice in this context is twofold: in America, it’s legal for a cop to kill you ‘to protect their life or the life of another innocent party’ — what departments call the ‘defense-of-life’ standard – or if you’re fleeing arrest and the officer has probable cause to suspect that you pose a threat to others.

The people who generally determine whether either of these two stipulations are applicable in police killings are the police departments themselves; very often the direct employer of the officer who fired the deadly shot or applied the deadly pressure. In this incomprehensible act of circular justice cops who kill are, of course, almost always deemed ‘justified’ by their colleagues.

Are they really justified killings? Impossible to know for sure, but pretty easy to make an educated guess that they can’t all have been.

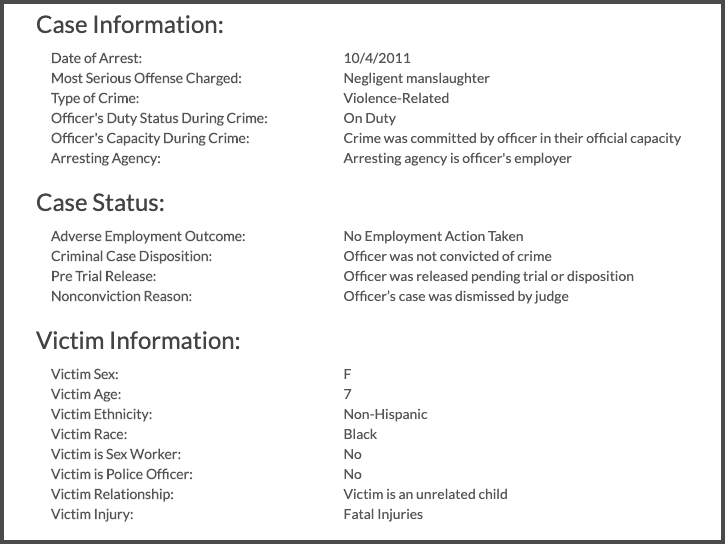

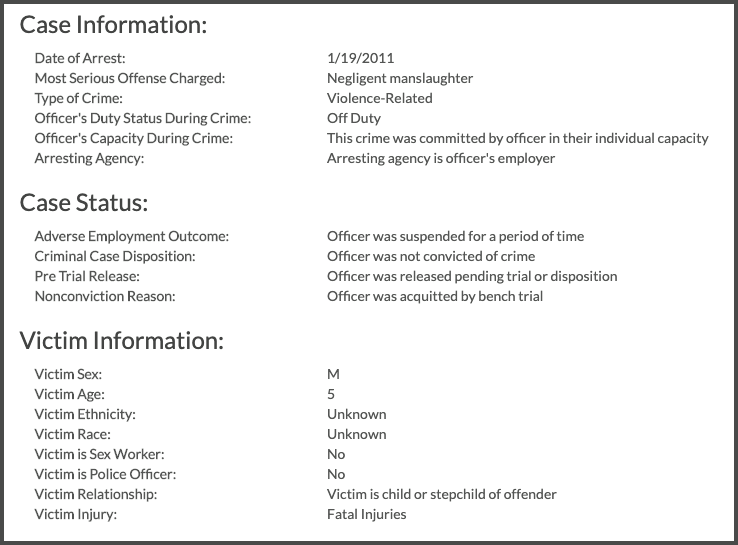

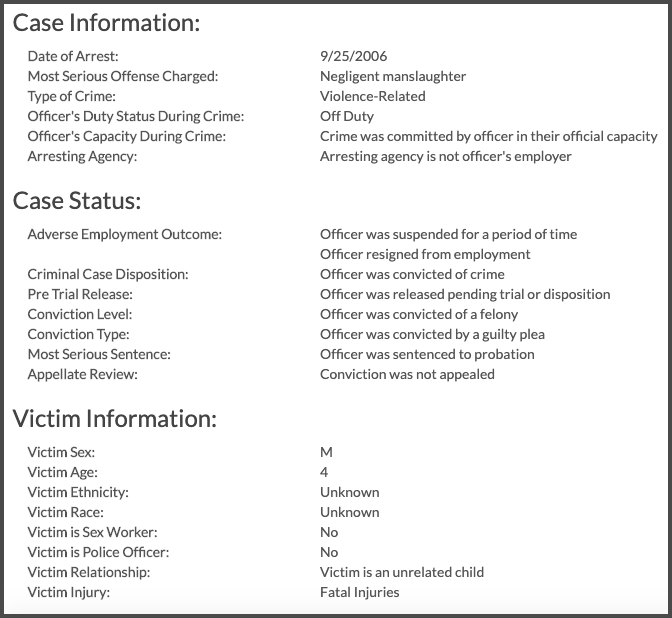

Whilst police crime is something of a black hole for facts, the Henry A. Wallace Police Crime Database is an independent project that houses information on 10,287 criminal arrest cases from the years 2005-2014 involving 8,495 sworn law enforcement officers. I’ll let you decide whether these few incident reports, picked at random, show justified killings as a result of an officer fearing for their life or apprehending a dangerous subject. The victims are 7, 5, and 4.

As these reports demonstrate, even if a police department has no choice but to bring charges against one of their own because, say, their act of egregious violence was captured on film, officers generally needn’t worry. Between 2005 and 2019, 98 non-federal law enforcement officers were arrested in connection with fatal, on-duty shootings. Of these, only 35 officers have been convicted of a crime (often a greatly reduced one) and only three have been convicted of murder and seen their convictions stand.

In this same time frame approximately 14,000 people died by police. That’s a 0.0002% conviction rate.

Please, take a moment to reflect on those numbers, and the fact that no matter how hard I try I cannot find the names of the three child victims above.

Chauvin should’ve got away with it, and he still might. Why?

The bias of the system

Racial bias is built into the foundations of the US system of law. This prejudice starts on the street with police. Black people are more than twice as likely to be killed by police as white people, according to data collected by The Washington Post since mid-2014. Civil rights leaders say black Americans are shot more because they are more likely to be pulled over.

The Minnesota police department, Chauvin’s former employer, is a great example of the kind of racist echo chamber that can crystallise around a justice institution under the right circumstances.

Minneapolis has a powerful police union with a history of fluidity between its board and local politicians. Though 20% of the city’s population is black, black people account for more than 60% of the victims in Minneapolis police shootings from late 2009 through May 2019.

As well as the video of Floyd’s last moments, the MPD’s record of racial violence includes Thurman Blevins, a black man who begged two white police officers closing in on him, ‘Please don’t shoot me. Leave me alone,’ in a fatal encounter captured on body-camera footage. His death two years ago led to protests across the city.

There was Chiasher Fong Vue, a Hmong man who was killed in December during a shootout with nine officers, who fired more than 100 bullets at him.

There was Philando Castile, shot by a police officer while being pulled over during a traffic stop. Jamar Clark was shot by police who responded to a paramedic call. Christopher Burns was strangled when two officers used a chokehold, and David Smith was restrained by police officers before he died of asphyxiation. All in Minneapolis.

Minnesota’s current police chief, a black man named Medaria Arradondo, had previously filed a lawsuit for racism against his own department when he was a lieutenant. He’s currently struggling to overhaul the institution.