We spoke to Ghislaine Fandel – who is a resource developer and content creator for Subject to Climate, as well as an SDG13 Ambassador for Social Impact Movement – about all things energy.

Ghislaine Fandel is a resource developer and content creator for Subject to Climate, as well as an SDG13 Ambassador for Social Impact Movement.

The science expert is currently studying for her MSc in Sustainable Development and writes for numerous publications about environmental justice.

Given climate science and communication have played such a significant role in her experience to date, we thought it fitting to speak with her on day nine of COP27, the theme of which is energy.

Delegates will be looking at how new and developing technologies, such as green hydrogen, could help in the envisaged global just transition to net zero.

There will also be further discussion of how this transition, which is cheaper than continuing with fossil fuels, will be funded.

View this post on Instagram

Thred: What are your general views of the climate conference?

Ghislaine: I agree with the general idea, with the concept of having a place of gathering for politicians, scientists, activists, protestors, civilians, innovators etc. but at the same time I don’t know if that’s essentially what we’re seeing at COP right now. It isn’t really what COP is at the moment, nor what it has been in the past few years. To name a few obvious examples, seven of the 110 delegates at COP are women, over 600 people are representing the interests of the fossil fuel industry, and most youth and protestors have been physically separated from the rest of the event.

Tied together, these things lead to more harm than good. COP has also been a bit performative for some, if not many, countries when it comes to actually committing to climate action and following through with these commitments. On the other hand, for others it provides a platform on the world stage. It hasn’t, however, been doing this with sufficient representation for the Global South.

Thred: We’re all wondering what we can expect from the outcomes of the talks and commitments today. Do you see COP as a genuine path towards a clean energy transition or is it a lost cause?

Ghislaine: COP is important in that it highlights both achievements and failures when it comes to countries and their clean energy transition. This is important because it highlights them for activists, and people living in these countries who are exposed to climate change. In exposing that gap between where we are now and where we need to be we can engage more people and call for more action.

At the same time, it’s hard to say that it’s a lost cause because I so badly want to put hope into this. I think COP is important for charting a path for a clean energy transition, but that’s more around math and that math is only going to take us so far unless we actually act on it.

Thred: Though people, politicians, and companies are now well-aware of the implications of inaction around fossil fuels, sustainable energy still constitutes a considerably small portion of what we use on a daily basis. Why do you think there still has not been a more decisive move towards sustainable options, despite us being so clearly aware of the need to change?

Ghislaine: We all know that we need this transition towards clean energy and away from fossil fuels. I’d like to point to what I previously mentioned regarding the number of fossil fuel representatives that are acting on behalf of coal, oil, and gas, and who are present at the world’s biggest climate conference right now. The fossil fuel industry has positioned itself on purpose to be considered necessary for development, economic prosperity, and even for wellbeing in a lot of places. This has been enabled by many of the political and economic systems that we have in place, and it now holds a lot of power over those same systems.

When you pair the short-sightedness of a lot of politicians with an industry that is so willing to do whatever it takes to maximise its profits and remain relevant in an economic sense – even in a political sense – with the imperialistic and the neo-colonial mindset that is dictating the relationship between countries right now, it leads to where we are today: facing a lack of decisive action that allows for a clean, just, and equitable energy transition.

There are a lot of factors at play. When we talk about how relevant fossil fuels remain versus how relevant clean energy is right now, we also have to talk about the consumption side of things. Because even though we’re producing more renewable energy, more clean energy – which is fantastic – demand is also rising. Essentially the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix remains largely unchanged. For a clean energy transition we need to address both that supply and that demand. More people – specifically those in high-income countries – need to realise that energy use is highest in these countries.

It’s important to accept that there’s going to be a need to reduce consumption in order to allow for this transition. As low and middle-income countries continue to develop and use more energy, as is their right, the Global North needs to make space in terms of energy usage because right now to live like an American or Western European is simply so unsustainable.

Thred: You’ve stressed the importance of viewing this from both sides. On this note, what role do you think activists and the scientific community should play in making sure policies are enacted?

Ghislaine: I think we all carry certain levels of responsibility when it comes to the climate crisis. Some significantly more than others. But activists and the scientific community (and I can’t stress this enough) are critical to climate action for a number of reasons. For one, accountability. I’m referring to ensuring that politicians are actually committed to and acting on their promises.

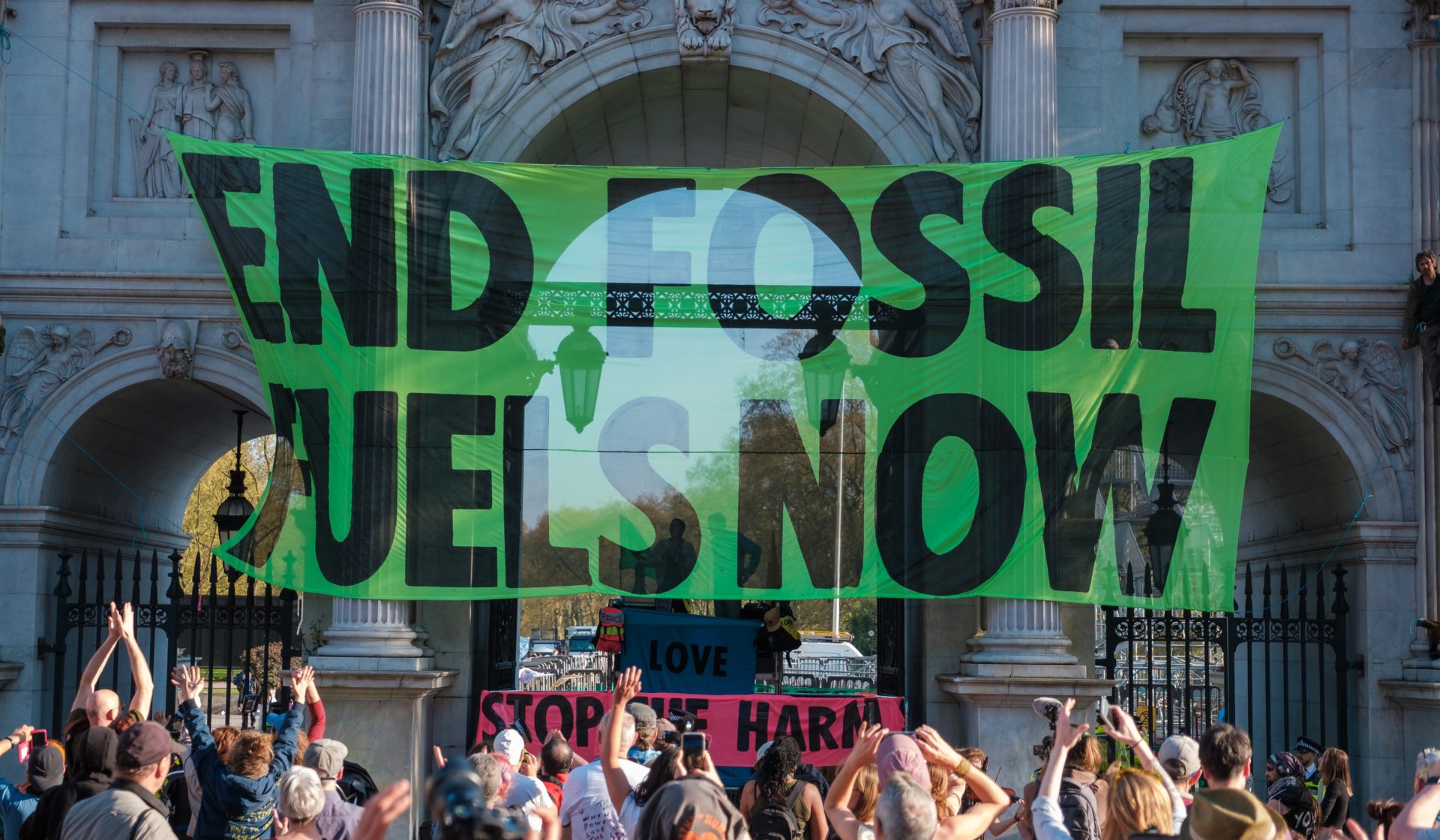

For this, I think we need greater inclusion of activists and scientists on advising on policy which is not where we are today. We can see it at COP27. There’s the Youth Pavillion but in some ways that separates the youth from the discussion. We need to ensure that these activists and scientists are heard because otherwise they’ll continue resorting to civil disobedience in the name of climate action. This, however, is necessary right now because governments aren’t paying enough attention to this issue and aren’t committing to it largely enough. That work is critical and it’s often undervalued and misrepresented.

I think on top of this, there comes the education aspect of it which is more where my work has aligned. People really need to know the truth behind the urgency – not just that climate change is happening – and the severity of the situation that we’re facing and that so many people right now are being exposed to and affected by. In all parts of society. That’s not just educating on the science behind climate change, but on the role of factors like racism, misogyny, and colonialism (to name a few).

The climate movement needs help and the more people that are educated on the issue – that are burdened but also empowered by this knowledge – the more problem solvers, leaders, and advocates we have standing up for the natural world and for the environment.

Thred: What do you think is the best approach to teaching people about climate science? Especially now when young audiences in particular are so overwhelmed with such a high degree of terrible news on and offline. What’s the best means of bringing awareness to the issue?

Ghislaine: Lots of different people make up an audience so it can be really challenging and difficult even to communicate climate change in an effective way because it’s also so multifaceted. But I think that there are a few critical elements. One, for example, is accessibility. This can mean that climate education is free. Another can be simplifying language. Because it’s often seen as such a complex issue and when we talk about the science behind the solutions it can be complicated. Ensuring that the information is accessible to people is important for them to not only feel empowered by the knowledge that they’re gaining on it but on their ability to communicate it further to the people around them.

It’s also important to relate to people. Empathy and compassion is so necessary. Engaging people with stories of the reality of the situation. Everyone’s going to be exposed to climate change at some point, but a lot of people are just hearing about it right now. Talking not only about the stories of those who are falling victim to the costs of climate change, but also the solutions that have come out of these communities, their resilience, and their strength in adapting. This ties into the hope aspect of it because, as you said, so many people are exposed to really awful news on a daily basis so when we talk about solutions – not just these big ones like energy – we need to pair it with calls to action. Climate anxiety comes out of this and people need hope, they need something tangible to work towards that will keep them motivated.