Limiting global warming to 1.5-2°C means cutting fossil fuel production yearly while keeping coal, oil, and gas in the ground. But what does this mean for the world’s most carbon-emitting industry?

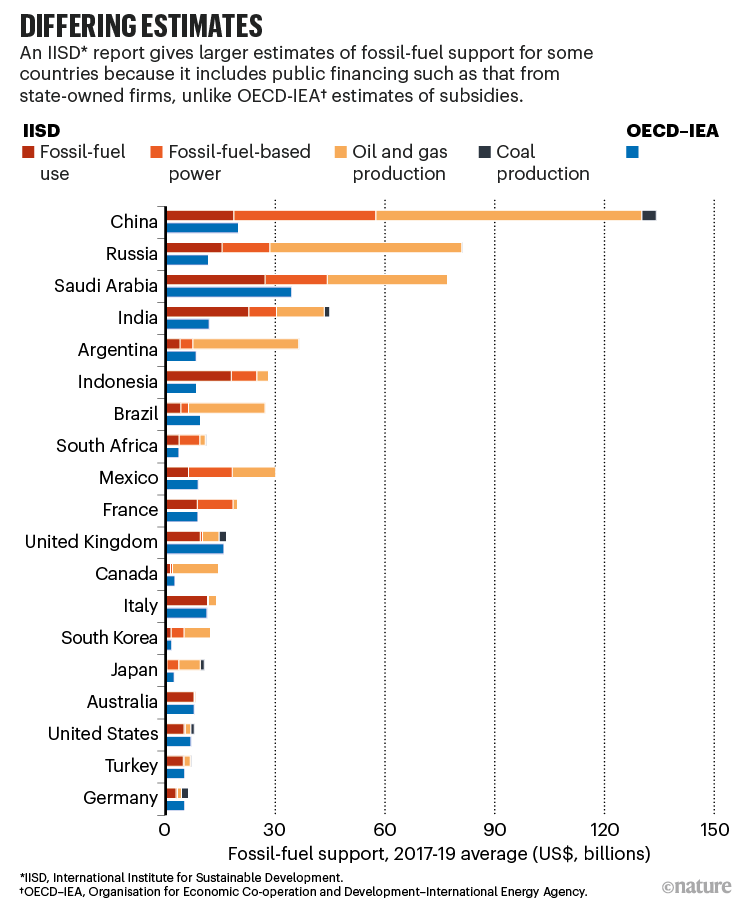

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, supporting fossil fuel production is not aligned with our essential low-carbon transition.

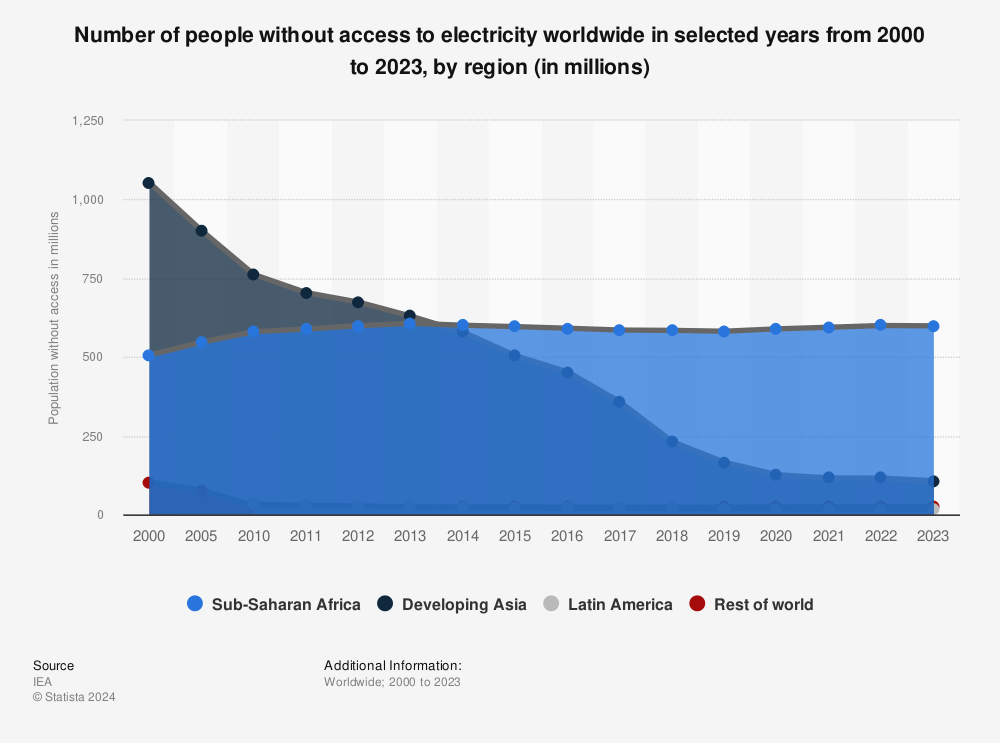

Experts consider the just and equitable shift away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy to be a critical and necessary step in solving climate change. With fossil fuel titans having known about their impacts on the climate for decades, this is ample time to prepare for this transition.

The industry’s actions, however, speak volumes to their continued unwillingness to address the climate crisis.

In 2021, amidst reports that 60 percent of oil and gas and 90 percent of coal must stay in the ground to sufficiently limit warming, fossil fuel production continued to rise. In the same year, a now ex-executive of Exxon touted the company’s efforts to mislead the public and advocate for solutions they did not consider politically feasible, like a carbon tax.

These efforts follow a decades-long shift in the industry’s strategy from one of climate denial and misinformation campaigns to one of fossil fuel solutionism, greenwashing, techno-optimism, and vague ‘net-zero by 2050’ targets.

But for every year they delay effective climate action, they leave behind increasing temperatures, rising sea levels, environmental damage, and human rights violations in their wake.

To limit these impacts is to first acknowledge and address climate delay perpetuated by the fossil fuel industry (and then some).

According to United Nations Secretary General, António Guterres, ‘Instead of slowing down the decarbonization of the global economy, now is the time to accelerate the energy transition to a renewable energy future.’