The 27th annual UN Climate Summit concluded on Friday in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. Here’s a roundup of what was achieved, what missed the mark, and the most important points made by the 13 Gen Z activists we held thematic conversations with during the last fortnight.

Though COP27 was meant to conclude last Friday, delegates were furiously working on the final decisions well into the weekend.

The results of the latest UN Climate Summit were only unveiled on Sunday morning after gruelling debates over funding and fossil fuel emissions forced negotiations to drag on almost two days longer than expected.

Countries failed to commit to phasing out, or even phasing down, all fossil fuels. It’s a glaring omission that’s alarmed climate scientists and experts who warn that stronger action and sharper cuts are necessary to limit warming.

However, the deliberations did culminate in one key breakthrough, which was a hard-fought agreement to set up a ‘loss and damage’ fund. This will offer vulnerable nations financial assistance in dealing with the natural disasters they’re being battered by.

Let’s examine the main takeaways from the last fortnight. Did the outcomes take necessary measures to adequately tackle the crisis we’re running out of time to confront?

View this post on Instagram

What was achieved at COP27?

Loss and damage

Following three decades of pressure from developing nations, the EU made a last minute U-turn on blocking loss and damage efforts.

The result – which is being hailed as the most significant advance since the Paris Agreement at COP15 – is a new arrangement that establishes a fund to help low-income, highly-affected countries bear the immediate costs of extreme weather events caused by global warming.

According to the agreement, the fund will initially draw on contributions from developed countries and other private and public sources like international financial institutions to assist these nations with rebuilding their physical and social infrastructures.

Though the more contentious issues regarding the fund (such as what the criteria to trigger a payout will be and how exactly the money should be provided) were pushed into talks to be held next year, its adoption displays a dedication to rebuilding trust and standing in solidarity with the Global South.

Adaption over mitigation

While mitigation has long taken centre stage in negotiations on where to direct climate finance, world leaders at COP27 made sure to highlight the need for more adaptation focused solutions.

In short, recognising the ever-diminishing time frame we have to reduce the severity of the crisis, they turned their attention to how nations should be working around it to become more resilient to the impacts of ecological breakdown.

The outcome of this is a comprehensive global to-do list to help improve the resilience of more than four billion people against climate-related risks, with proposed measures including flood defences, seawalls, wetland preservation, mangrove swamp restoration, and forest regrowth.

Building on this, the UN launched a new action plan (which it’s asking governments to invest $3.1bn into) to implement early warning systems in fragile regions.

Protecting biodiversity

Despite concerns that not enough was said about nature ahead of COP15, a specially dedicated and separate biodiversity conference, hopes were raised by the attendance of Brazil’s new president, Lula de Silva, who pledged to do everything in his power to save his country’s rainforests – in contrast to previous years’ fears about their fate under Bolsonaro.

Devoted to dramatically reducing deforestation in the Amazon, he confirmed that Brazil is seeking co-operation with Indonesia and the DRC on conservation, as well as the creation of a council of Indigenous Leaders with whom he seeks to collaborate more closely with on protecting Brazil’s biodiversity.

Not only this, but some 140 countries officially launched the Forests and Climate Leader’s Partnership to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation.

Other notable achievements include the publication of a net-zero ‘guidelines’ paper intended to be a ‘single core reference text’ for organisations wishing to credibly create meaningful targets, the US doubling its previous commitment of $4bn to $8bn to prepare the agriculture sector for the effects of climate change, and Germany signing a deal with Egypt to advance green hydrogen.

The COP27 deal also says that ‘safeguarding food security and ending hunger’ is a fundamental priority, and that communities can better protect themselves from climate effects if water systems are protected and conserved. However, regardless of how welcome these new additions are, they are not supported by actions that need to be taken nor any dedicated funding to promote them.

What missed the mark?

Outside of these achievements, progress was limited.

For starters, the mandatory phasing out of fossil fuels was noticeably absent from discussions, despite a commitment at last year’s summit to at least begin reducing coal extraction and a stronger-than-usual industry presence at this year’s.

In fact, although some countries – surprisingly led by India – vocalised their ambitions to stop burning gas, oil, and coal (accounting for 40 per cent of all annual emissions) at COP27, this proposal failed and the resolution reached was the same as that in Glasgow.

This had a lot to do with the current energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which loomed large during the negotiations and saw language calling for a fossil-fuel-phase-out jettisoned from the final text.

In its place is now a reference to ‘low emission and renewable energy,’ which is being considered a problematic loophole that could allow for the development of further gas resources, as gas produces less emissions than coal.

Finally, adding insult to injury, while one of the primary goals of COP27 was to strengthen COP26’s emissions pledges – which are desperately required to ensure global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius – no such commitments were made in Egypt.

Rather some countries actually tried to back out on their promises to stay within the limit and to abolish the ratchet mechanism.

Fortunately, they failed, but a resolution to cause emissions to peak by 2025 was removed from the final text, to the dismay of those familiar with the IPCC’s recent warnings of the catastrophes set to arise if we don’t act soon.

Among them are the heating of the Amazon, which could turn the rainforest to savannah, transforming it from a carbon sink to a carbon source, and the melting of permafrost that could trigger a ‘methane time bomb.’

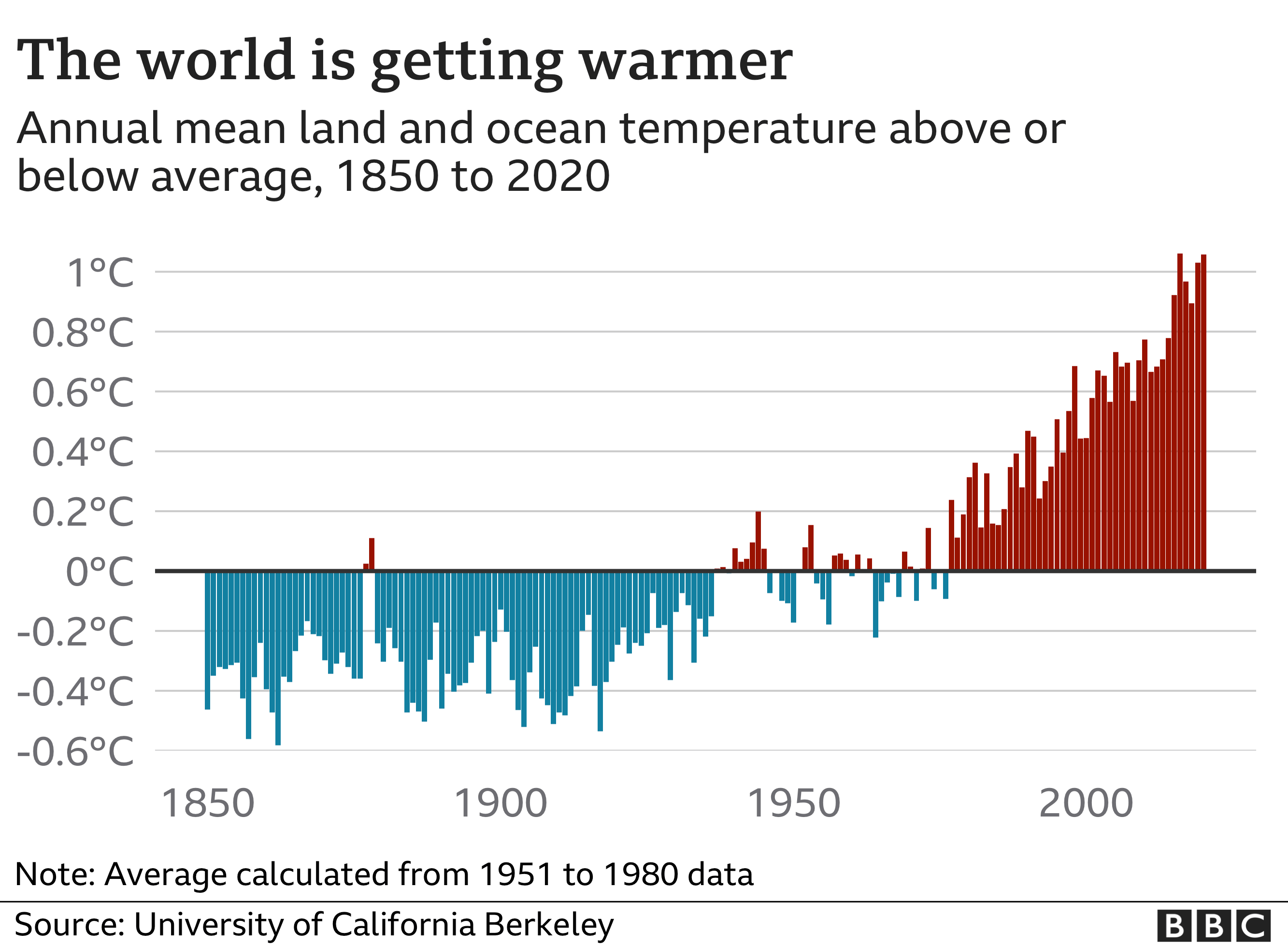

This has led many to conclude that the world is destined to heat beyond this limit, an apt expectation given there’s a fifty-fifty chance we’re likely to pass it permanently by 2031.

For a year billed to be all about ‘implementation,’ it seems we’ve fallen short.

‘There was no backtracking. Which as a result, one could say, is highly unambitious. And I would actually agree,’ UN Executive Secretary for Climate, Simon Stiell, tells The Associated Press.

‘To say that we have, stood still. Yeah, that’s not great.’

This is a sentiment echoed by the 13 Gen Z activists we spoke to during COP27, all of whom shared valuable insights into how we should be feeling about the topics covered at this year’s summit.

In conversation with 13 Gen Z activists

Melati Wijsen – World Leaders Day

Thred: With political turmoil and economic spiralling overshadowing our climate goals, are the current pledges too ambitious or unrealistic? Can we ever really reach them?

Melati: Given current circumstances, I think they’re within reach and they should be priority for everyone. If we don’t start focusing on climate change there will be more war and pandemics.

Clover Hogan – World Leaders Day

Thred: In the context of previous efforts (or lack thereof), do you deem the goals outlined so far within reach or too ambitious? What should we measure the success of discussions by?

Clover: Even if a lot of world leaders are in denial, the urgency of these solutions is hard to ignore. We’re going to see runaway climate change in many parts of the world if we fail to limit emissions and that’s terrifying because even many of the global commitments that have been made so far don’t put us on that path – let alone action. There are already so many people living through climate change, already being displaced, already losing their lives and their livelihoods. They don’t have a choice to say it’s too late or too far gone. For them, it’s do or die.