A mixed-race woman appears to be the third person ever to be cured of the virus with a new approach that holds the potential for curing more people of racially diverse backgrounds.

Globally, 37.7 million people were living with HIV at the end of 2020 (according to WHO).

In Africa, it affects nearly 1 in 25 adults, with the region alone accounting for more than two-thirds of that staggering worldwide statistic.

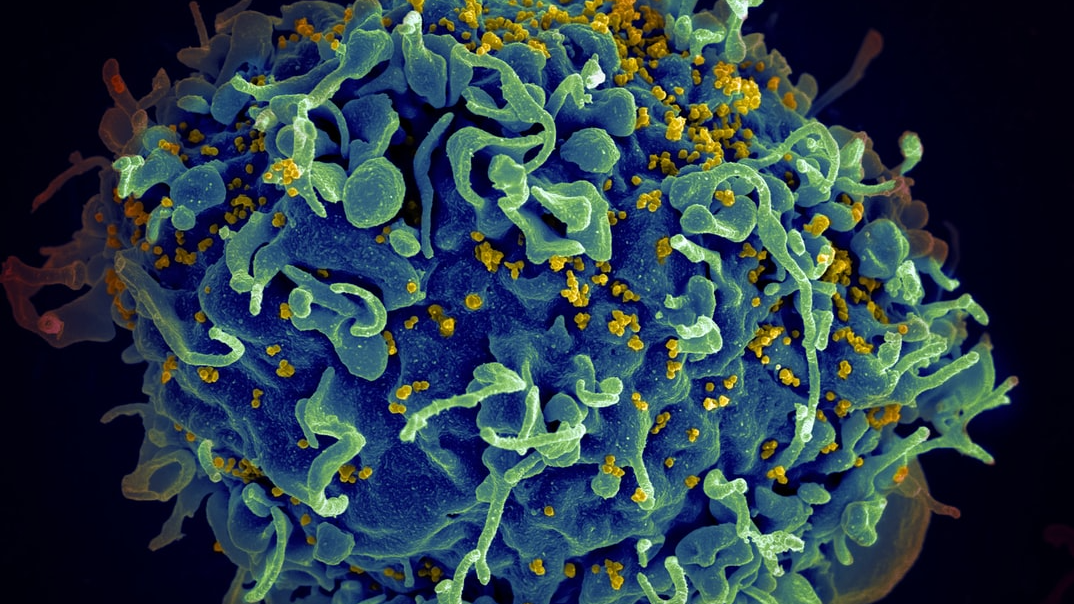

Since the immunodeficiency virus initially emerged in the population, science has played a crucial role in tackling the epidemic.

And while hundreds of thousands still die from HIV-related causes every year, available remedies such as antiretroviral therapy – which also reduces the risk of transmission – continue to help more and more of those testing positive live longer, healthier lives.

But for decades, there hasn’t existed a cure.

Until today, that is, because scientists may have just discovered a breakthrough treatment which holds the potential for curing more people of racially diverse backgrounds (aka those most impacted) than was previously believed to be possible.

Using a novel stem cell transplant method which they hope could be administered to dozens annually, a group of American researchers in Colorado were able to cure the third person on Earth of HIV.

It marks the first time a female (in which HIV develops and progresses differently) and a person of colour has ever had the disease eradicated from their system.

Leaving the hospital just 17 days after her transfusion, she suffered minimal side effects compared to her male predecessors, was off HIV medication 37 months post-op, and over a year afterwards has yet to experience any resurgence.

The woman, who is of mixed-race, received umbilical cord blood which is particularly revolutionary because it’s more readily available than the stem cells often used in bone marrow transplants.

It also doesn’t need to be as closely matched to the patient; another advantage given that most donors are Caucasian.