Scientists at the University of Utah believe firing millions of tons of moon dust into the atmosphere could help to prevent global warming.

The best answer is often the simplest… is a mantra being emphatically shunned by climate scientists at the University of Utah.

The group of researchers at the institution have been running computer simulations to test what is undoubtedly the most unorthodox climate mitigation scheme yet: launching millions of tons of moon dust into our atmosphere to reduce global warming.

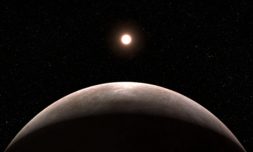

Falling under the fundamental bracket of solar geoengineering, it is theorised that clouds of lunar dust could shade the Earth from enough of the sun’s rays to drive the planet’s temperatures down.

It may sound like a child’s sci-fi submission to Blue Peter, but scientists genuinely believe this ‘high-porosity, fluffy’ material would be perfect for absorbing light energy, scattering photons away from Earth.

In terms of logistics (many of which, unsurprisingly, haven’t yet been addressed), 10 million tons of dust would need to settle 1.5 million kilometres away at the first Lagrange point – L1.

Here, the gravitational pull of the sun and our planet cancel out and objects remain in a fixed position for days until eventually dispersed by solar winds.

The team of scientists modelled this exact scenario in a simulator and discovered that a dust shield of 1 million tons at L1 could dim Earth-bound sunlight by 1.8% in a year. This is equivalent to completely blocking out an entire six days’ worth of sunlight.