Though scientists still know little about the long-term effects of e-cigarettes on the human body, they just found the devices to be causing significant cellular and molecular changes in the lungs.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ll know that vapes are all the rage.

Replacing one of the leading causes of preventable death worldwide, these days they are, quite literally, everywhere.

Regularly seen in the hands of young people due to their affordability, the popularity of these small, brightly-coloured, single-use devices has far surpassed that of cigarettes.

This was confirmed by several recent studies, one of which found the number of British smokers to have dropped below 15 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 compared with a dramatic uptick in vaping from one to 57 per cent during 2021.

Yet surprisingly, fairly little remains understood when it comes to the health implications of inhaling vapes on a regular basis.

Until now, the only downside to this favoured (and flavoured) alternative to puffing on a slender harbinger of disease has been the supposed ‘popcorn lungs’ you might develop if you’re addicted to it.

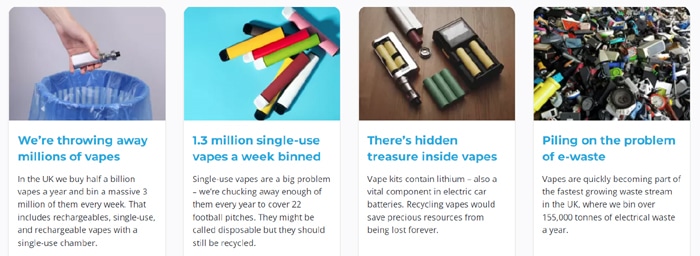

That, and the obvious environmental repercussions of our obsession with this lesser of two evils.

Unfortunately, as is often the case with rumours and (regrettably) alarming information about our planet’s demise, none of this has succeeded in convincing the masses to ditch their shiny plastic nicotine sticks once and for all.

This new study might, however. It comes amid the boom in vaping product sales across the globe, which has scientists more concerned than ever before about the habit’s unidentified long-term effects on the human body.

To address the gaps, co-author Carolyn Baglole and her team studied how eight to 12-week-old mice were affected by vaping, when exposed to it three times a day over a four-week period.

Using Juul vapour, the mice were hotboxed with one group experiencing a Juul smoke regime of three 20-minute puff exposures per day, for a month.