Testing humanity’s ability to prevent the kind of disaster that wiped out the dinosaurs, NASA intentionally crashed its DART probe into an asteroid.

The threat of a devastating asteroid may seem fanciful, but scientists understandably want to prepare for a dinosaur-esque situation.

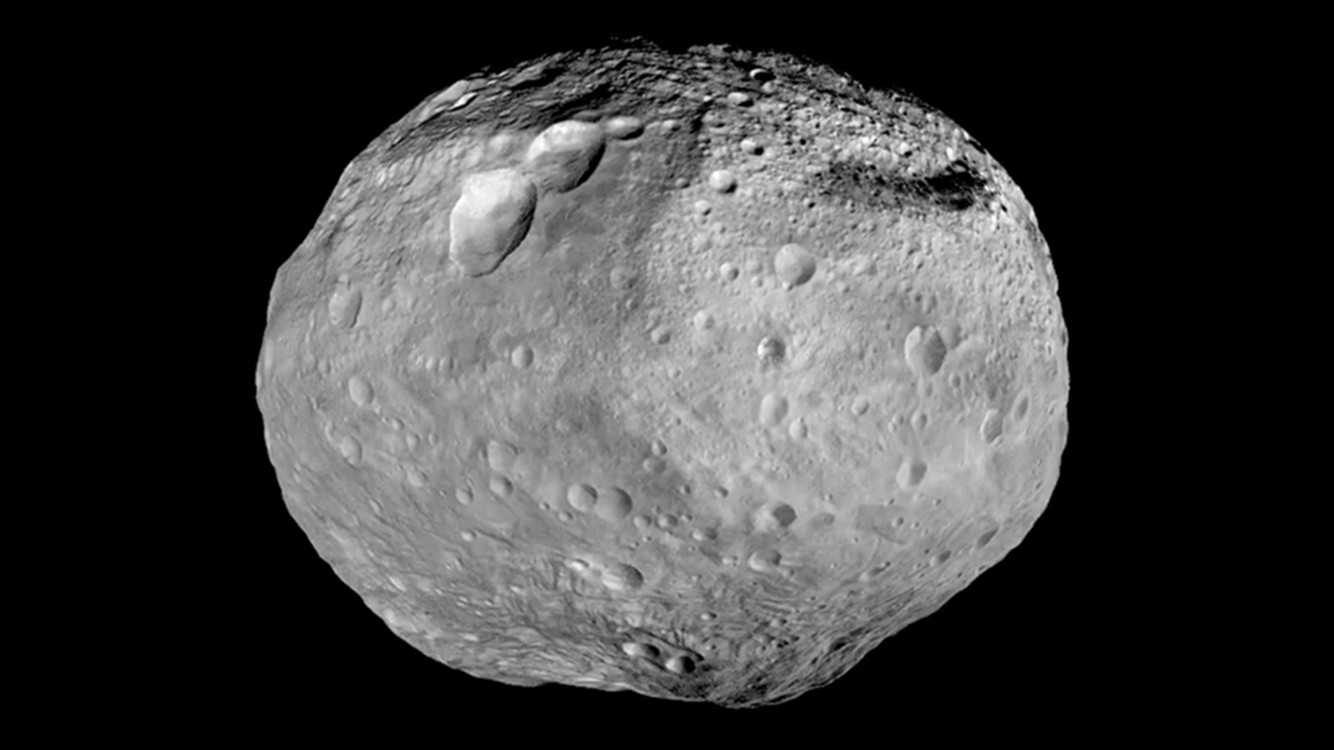

It’s for this reason that, last November, NASA launched DART (short for Double Asteroid Redirection Test), a vending-machine-sized spacecraft with one target: Dimorphos.

Almost a year on and the $325m mission was a success.

This morning, the probe collided head-on at 15,000mph with the 160m-wide cosmic object, which has been orbiting the sun some 6.8 million miles away for eons without threatening the Earth – making it the ideal save-the-world candidate.

Yet despite the impact, DART (weighing just 570kg in comparison with the asteroid’s 5bn kg) did not shatter Dimorphos.

This is because NASA was cautious towards the potential damage that flying debris from the planned self-destruction could do to our planet.

Instead, it slowed Dimorphos down. Over time, this should have a measurable effect on its orbit.

The historic event marks mankind’s first attempt at moving another celestial body and suggests we may well be able to avoid experiencing the plot of Don’t Look Up first-hand.

‘It’s a new era of humankind in which we potentially have the capability to protect ourselves from something like a dangerous, hazardous asteroid impact,’ declared Lori Glaze, NASA’s planetary science division director.

‘This is when science, engineering and a great purpose, planetary defence, come together, and, you know, it makes a magical moment like this.’

Before we get ahead of ourselves, however, it’s important to understand that we won’t know for sure if the spacecraft carried out its ultimate objective of altering Dimorphos’ trajectory until at least the end of October.

This aside, the outcome so far has been touted as ‘ideal’ for this stage of a test to determine whether or not intentionally crashing a spacecraft into an asteroid is effective.

It’s been especially welcomed by planetary defence experts who would want to nudge a threatening asteroid or comet out of the way, given enough lead time, rather than blow it up and create multiple pieces that could rain down on us.

‘It was basically a bullseye. I think, as far as we can tell, the first planetary defence test was a success, and we can clap to that,’ said DART deputy programme manager Elena Adams.

‘Earthlings should sleep better, and I definitely will.’