By feeding honey water to bears, researchers have discovered the potential genetic key to their insulin control. This advance could lead to a remedial treatment for a disease that affects almost ten per cent of the world’s adult population.

If you’ve ever found yourself wondering why humans aren’t able to consume tens of thousands of calories a day to bulk up before taking a very long nap, you’re not alone.

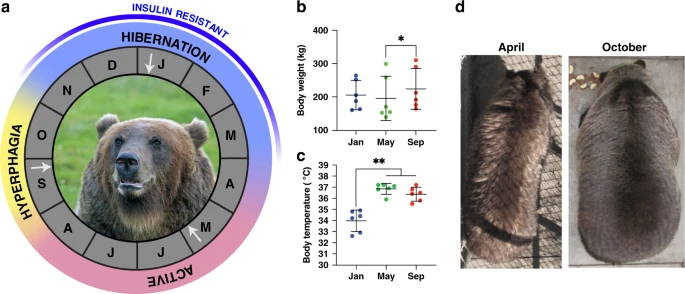

It’s a phenomenon that’s had scientists scratching their heads for decades, long-questioning why the same behaviour doesn’t cause diabetes in bears the way it would us if we were to rapidly gain a lot of weight then suddenly stop moving for months on end.

This week, however, researchers at Washington State University made a breakthrough.

By feeding honey water to the drowsy mammals, they discovered the potential key to their insulin control. The results could ultimately lead to a remedial treatment for a disease that affects almost ten per cent of the world’s adult population and can cause heart attacks, strokes, and blindness.

‘This is progress toward getting a better understanding of what’s happening at the genetic level and identifying specific molecules that are controlling insulin resistance in bears,’ explains Blair Perry, the study’s co-first author and a WSU post-doctoral researcher.

‘There’s inherent value to studying the diversity of life around us and all of these unique and strange adaptations that have arisen.’

Insulin is a hormone found in most warm-blooded creatures that regulates the body’s blood sugar levels by telling the liver, muscle, and fat cells to absorb this source of energy.