A new study has found that watching deepfake videos and reading short text descriptions of made-up remakes can cause people to falsely remember watching non-existent films.

Last month, researchers at University College Cork in Ireland published findings from their research into false memories, a study which indicates that the impacts of generative AI programmes may be more complicated than initially feared.

Deepfake tech has already proven itself a dangerously effective means of spreading misinformation, but according to the report, deepfake videos can alter memories of the past, as well as people’s perception of events.

To test their theory, the researchers asked nearly 440 people to watch deepfaked clips from falsified remakes of films including Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie in The Shining, Chris Pratt as Indiana Jones, and Will Smith in The Matrix.

They did not immediately tell participants that the films weren’t authentic, in order to better understand the impact of deepfakes on a person’s memory and added real film remakes to the mix for comparative purposes.

After watching four real films and two fake films in a random order, participants were asked if they’d seen or heard of the deepfaked versions before.

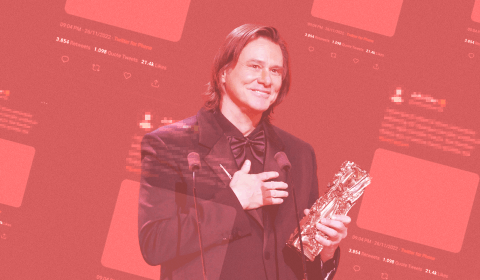

Deepfakes can be scarily convincing, but should we be worried about them distorting our memories of the recent past? Our new open-access paper looks at false memories for deepfake movie remakes @conorlinehan @johnjtwomey https://t.co/dAlq47YBB2 pic.twitter.com/b7p3LEuou3

— Gillian Murphy (@gillysmurf) July 13, 2023

Any of those who claimed to have previously seen the entire film, a trailer for it, or even if they agreed that they’d simply heard of it, were categorised as having a false memory.

As the paper states, 75 per cent of participants who saw a deepfake video of Charlize Theron starring in Captain Marvel falsely remembered its existence.

40 per cent of viewers falsely remembered the other three film remakes of The Shining, The Matrix, and Indiana Jones.

Interestingly, some went as far as to rank the movies that were never actually produced as being better than the originals – underscoring the alarming power of deepfake tech at distorting recollections of reality.