The innovative men’s apparel brand has finally cracked the code, using wood pulp and pomegranate peel to create a compostable material that breaks down within just three months.

Fast fashion has long-dominated the style landscape, providing an affordable and straightforward way for consumers to keep up with continually shifting trends. However, unlike the rapid nature of fashion fads – which come-and-go as quickly as TikTok challenges – the clothes and accessories we obsess over and promptly forget about can take decades and sometimes even centuries to decompose.

Fortunately, Vollebak is one of the leading fashion labels responding to this issue by creating a new generation of genuinely natural fabrics. The concept of ‘sustainable fashion’ is complex and multifaceted, and although big brands often use environmentally conscious marketing, it doesn’t necessarily mean their products are truly helping to lower the carbon footprint of fast fashion.

Vollebak is different though, with a dedicated focus on using materials from sustainable sources that can decompose quickly.

Founded by twin brothers Nick and Steve Tidball in 2016, the innovative men’s apparel brand now makes some of the world’s most technologically advanced clothing using unconventional raw materials like algae and plants. It’s a business model that’s becoming increasingly more viable as consumers begin to consider the entire life cycle of the garments they’re purchasing, from creation to end of wear, and not just the season’s most ‘on trend’ looks.

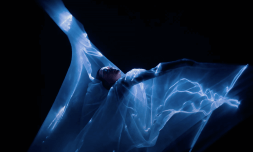

https://www.instagram.com/p/B1gwDQEhMoZ/

Striving to tackle the industry’s inherent overuse of chemical processing and synthetic dyes, the company has made minimising the environmental impact of alternative, eco-friendly materials its sole mission. Traditional manufacturing of clothing has caused serious harm to our planet’s ecosystems, polluting our oceans with microplastics and contaminating our water with harmful dioxins like chlorine and arsenic.

Vollebak doesn’t want to jump on the same bandwagon as other ‘sustainable’ brands by churning out products made from traditional fibres such as linen and wool which, while obviously beneficial for the planet, are not quite as viable a solution as algae, for example. In fact, engineered natural fabrics have the ability to turn into compost over mere months, which could radically transform the way clothing companies approach their production processes in the future. With this in mind, Vollebak has the potential to completely change the industry, particularly if its production methods pick up mainstream traction.

‘Humanity has already achieved the pinnacle of biodegradable clothing. The question is, what’s the modern version of that?’ says Steve. ‘On a long enough timescale, everything on Earth will biodegrade. What’s hard is making something that biodegrades very quickly, leaves no trace of its existence, and uses as little energy to create in the first place as possible.’

https://www.instagram.com/p/B1eKXZyh9EV/

Well, as ‘hard’ as it may have seemed, the brothers somehow managed to succeed in launching a revolutionary compostable t-shirt last year that transforms into humus without polluting the soil.

Since then, Vollebak has upped its game even further, unveiling fashion’s first ever totally compostable hoodie just last week. According to Steve it’s designed to break down within a maximum of three months when buried underground and ‘feels like a normal hoodie, looks like a normal hoodie, and lasts as long as a normal hoodie, but it starts its life in nature and is designed to end up there too.’