As the popularity of ethical fashion grows and consumers continue to seek out vegan clothing alternatives, it’s time we asked ourselves if these products are truly as sustainable as they seem.

It’s common knowledge that fast-fashion has long-dominated the style landscape, for the affordable and straightforward way in which it enables consumers to keep up with continually fluctuating trends.

However, unlike the rapid nature of these fads – which come and go as quickly as TikTok challenges – the clothes and accessories we obsess over and promptly forget about can take decades and sometimes even centuries to decompose.

That’s why, in 2023, many brands have begun offering solutions to previously eco-unfriendly practices, a result of public pressure to address the overall industry’s pollution problem.

Today, a significant shift in garment production is underway, fronted by a surge in the number of labels (both luxury and retail) experimenting with ‘cruelty-free’ replacements for conventional animal-based materials and collaborating with start-ups on the burgeoning technologies that make this possible.

One such alternative is faux leather, which has become increasingly popular in recent years as consumers seek to ‘veganise’ their wardrobes.

Even Kylie Jenner (the mother of materialism) has jumped on board, presenting a new collection earlier this month that’s made almost exclusively out of the stuff.

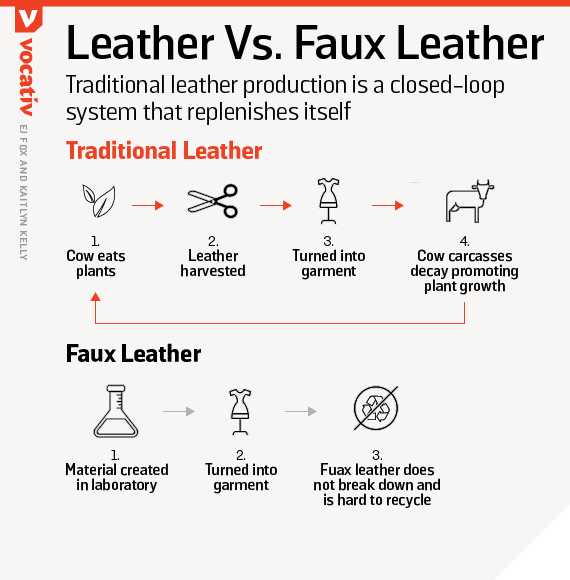

However, while faux leather is clearly the more ethical option in that it doesn’t require sentient beings to be killed in order for it to be made, sustainability-wise it’s rather a big no-no.

Not to mention the often appalling and exploitative human conditions in which it can be made, ‘largely in developing countries where environmental regulations are lax, sweatshops common, and child labour rife’ (Zoe Brennan).

Typically manufactured from synthetic fibres like acrylic, modacrylic, and polyester (all of which are types of plastic that don’t biodegrade), these polymers are derived from fossil fuels, which contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and the climate crisis that’s steadily spiralling out of control.

‘Faux leather in general is an inaccurate and vague term,’ says Jocelyn Whipple, a responsible materials specialist at sustainable fashion consultancy The Right Project.