What’s being done to address the racist policies and unfair judgements targeting Black people for wearing their natural hair?

With issues such as criminal justice reform currently dominating political discourse, confronting hair discrimination may seem inconsequential to some. What it represents, however, is another hurdle to overcome in our quest for racial and economic justice.

Routinely, POC individuals are forced to internalise the messaging that Black hair and its protective styles are inferior to what’s acceptable beneath the Western gaze.

In a 2019 research study carried out to identify the magnitude of this, 80% of Black, female participants reported having to change their hair to fit into a professional setting.

It also found them to be 1.5 times more likely to be sent home. Meanwhile, a 2020 Gallup poll concluded that one in five Black women feel social pressure to straighten their hair for work.

In the workplace, bias against hair texture and natural hairstyles commonly associated with people of African descent contributes to reduced opportunities for job advancement, particularly for women.

This must end. #PassTheCROWN #TheCROWNAct #HR2116 pic.twitter.com/afAEbUsNYu— Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (@RepBonnie) July 2, 2021

Within schools, Black hair is labelled as ‘distracting’ and ‘disruptive’ resulting in the exclusion and even expulsion of students. 46% of parents say that their children’s school policy wrongly penalises Black hair, and 1 in 4 Black adults recount a negative experience at school in relation to their hair texture.

‘Black hair is constantly scrutinised where our non-black counterparts do not face such opposition and contention,’ says creative director Wofai JE, who wrote a play titled Scalped covering this very topic.

‘As someone who’s worn locs, afros, twists, and braids for years, I realised that some opportunities have been denied to me simply because I was rejecting a European beauty aesthetic. We cannot find it acceptable for any of us to have to change our natural identity to gain employment or access to school.’

Among the many examples of this – namely teen wrestler Andrew Johnson being forced to either cut his dreadlocks or forfeit his match in 2018 – one incident stands out in particular: that of FINA announcing its decision to ban Soul Cap’s afro-friendly swimming cap from the 2021 Olympic Games.

‘The athletes competing at the international events never used, neither require to use, caps of such size and configuration,’ it said, adding that Soul Cap doesn’t ‘follow the natural form of the head’ and gives those wearing it an unfair advantage (a statement that’s in no way been backed by any scientific facts).

Though the undeniably racist ruling was put under review following global condemnation, it highlighted a lack of research into different cultures from official bodies. Soul Cap’s products are of course bigger than standard swimming caps because they’re designed to accommodate thicker hair. Prohibiting them only reinforces barriers into the sport for under-represented groups.

‘Having thicker hair doesn’t make Black swimmers less capable,’ said journalist Nyima Jobe.

‘But not having access to products that could make swimming more accessible and desirable could put more Black people off from trying it in the first place.’

So, what’s being done about it?

Since the YouTubers who changed the landscape for natural hair with their online movement in 2018, a fair amount indeed.

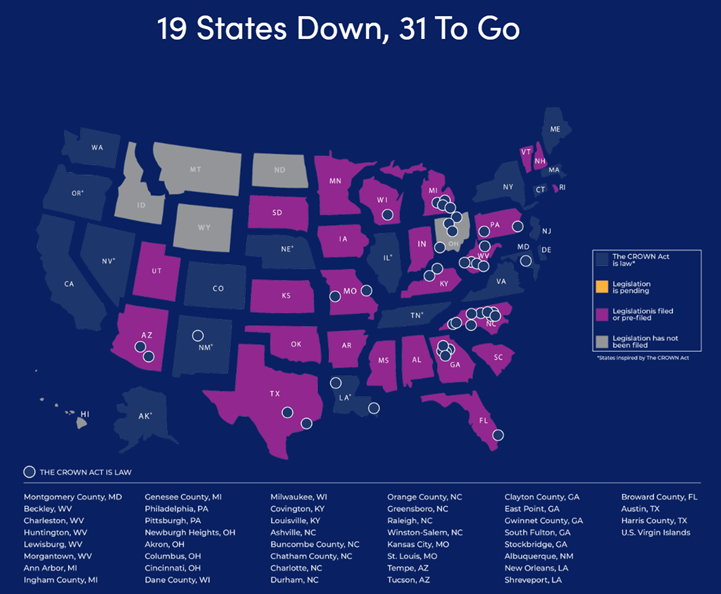

In the US, nineteen states and more than forty cities have signed The Crown Act (an acronym for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair), explicitly preventing discrimination against hair texture and style. It was proposed by the Crown Coalition, which believes race to be a social construct, defined not solely by skin tone, but shaped by hair as well.

‘We will continue to ensure we can use our crown to freely express who we are natively,’ says member and politician Katherine Clarke. ‘Discrimination against Black hair is racist. It stops equality in school and the workplace.’

Unfortunately, while it’s a huge victory for natural hair acceptance – encouraging BAME communities to embrace their Blackness and rebuke dominant standards of beauty that only recognises straight, “manageable” hair – the struggle persists, with 31 states yet to sign.