Details of the survey

Tebra asked a total of 1,000 people about their experiences with viewing medical content on social media. They quickly discovered that members of every generation are guilty of self-diagnosing.

On average, those surveyed spent 2.5 hours on social media. They estimated that at least 10 percent of the content they saw online was related to mental health.

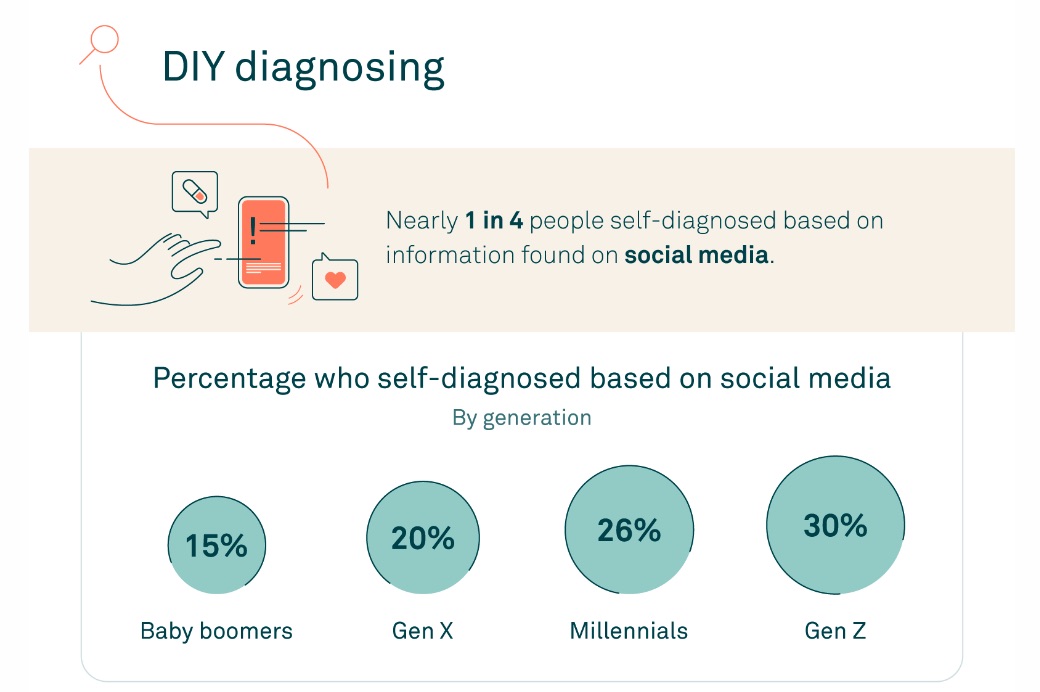

The survey results revealed that 1 in 4 people had diagnosed themselves with a mental or physical condition based solely on what they learned from these sources. Gen Z came out on top, being the most likely to do so.

This should be unsurprising as growing data pins Gen Z as the generation most avidly using social media. Over 38 percent of Gen Z spend in excess of 4 hours a day on such platforms and are consequentially more likely to come across health-related content.

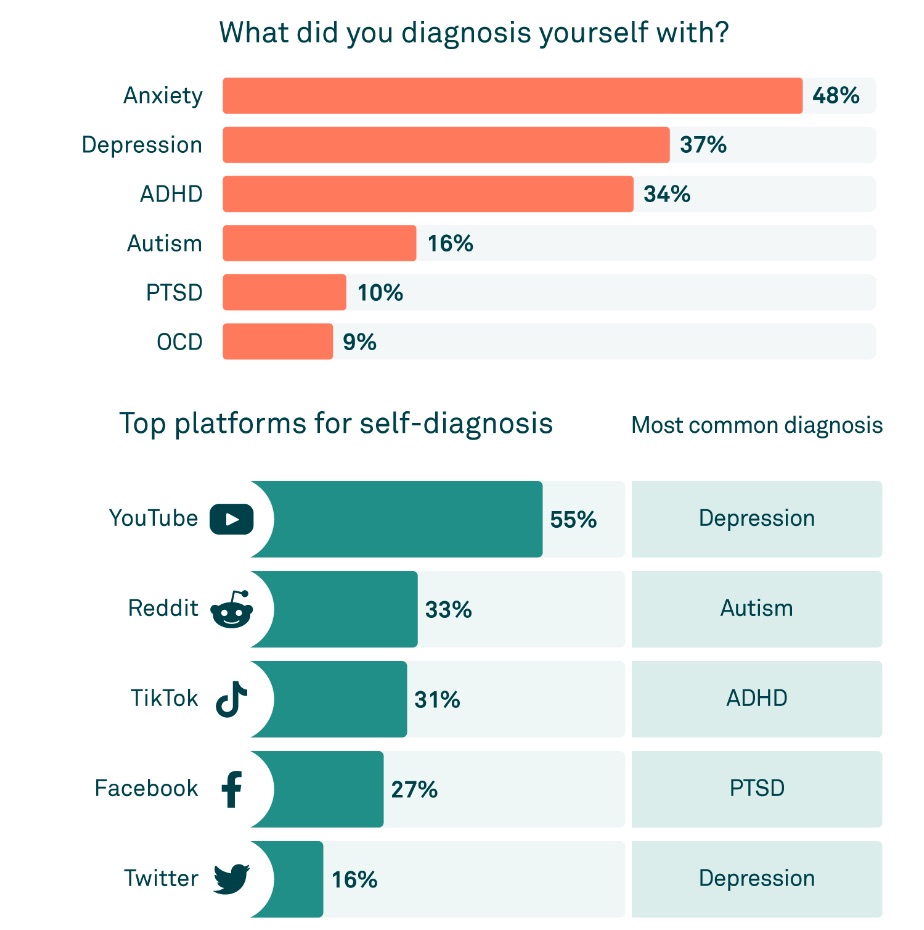

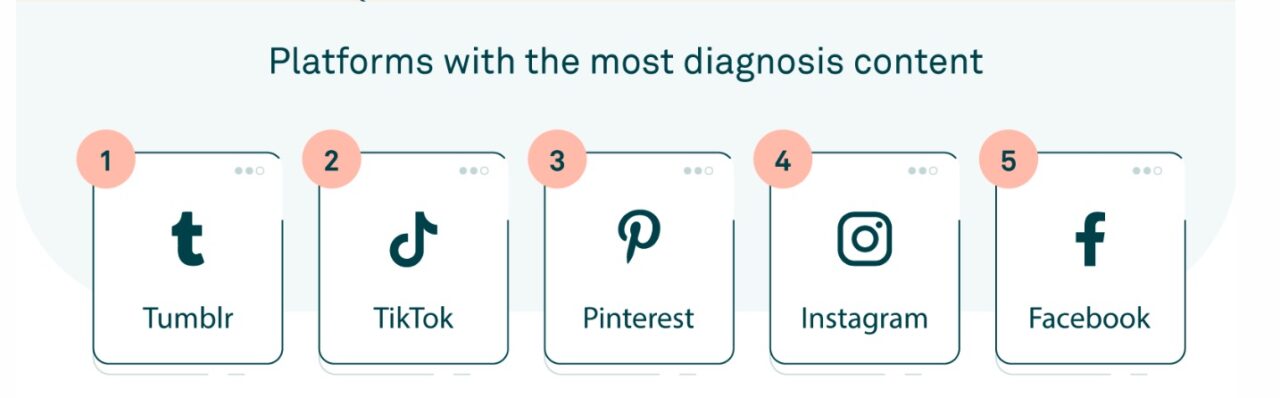

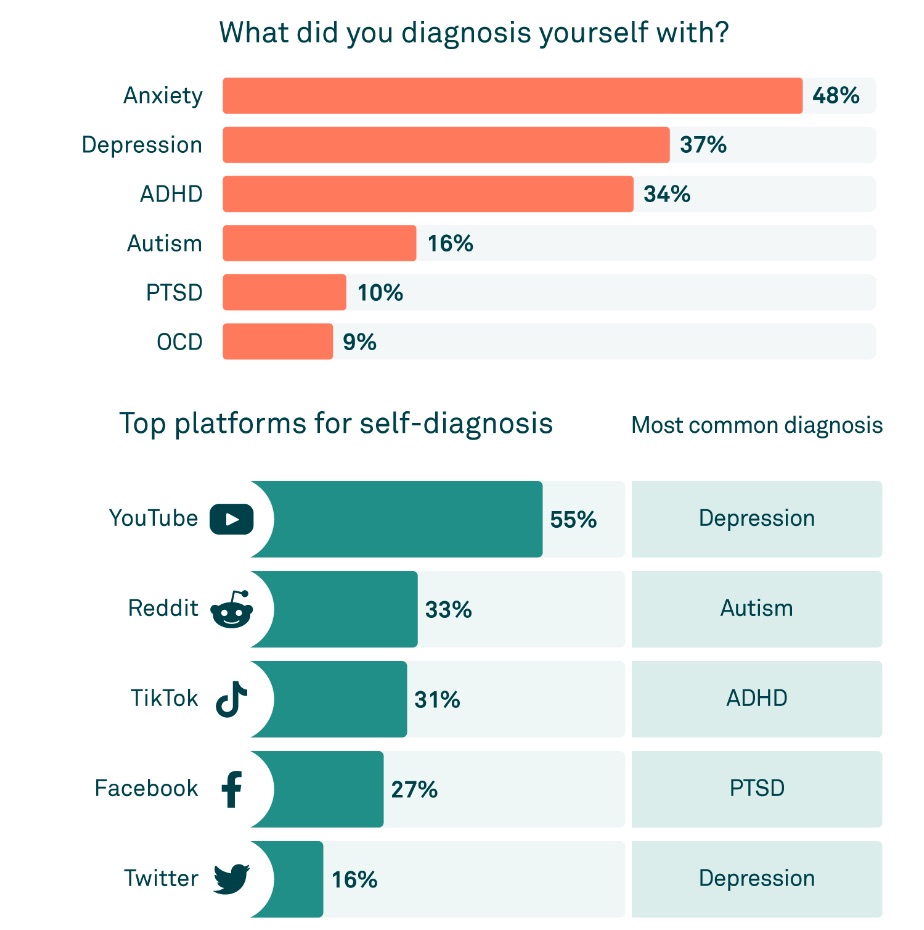

Tebra’s survey went further, investigating what exactly individuals were diagnosing themselves with and which platforms were providing information that led them to this conclusion.

The data for these queries is available in the visual chart below.

Did self-diagnosis lead to positive action?

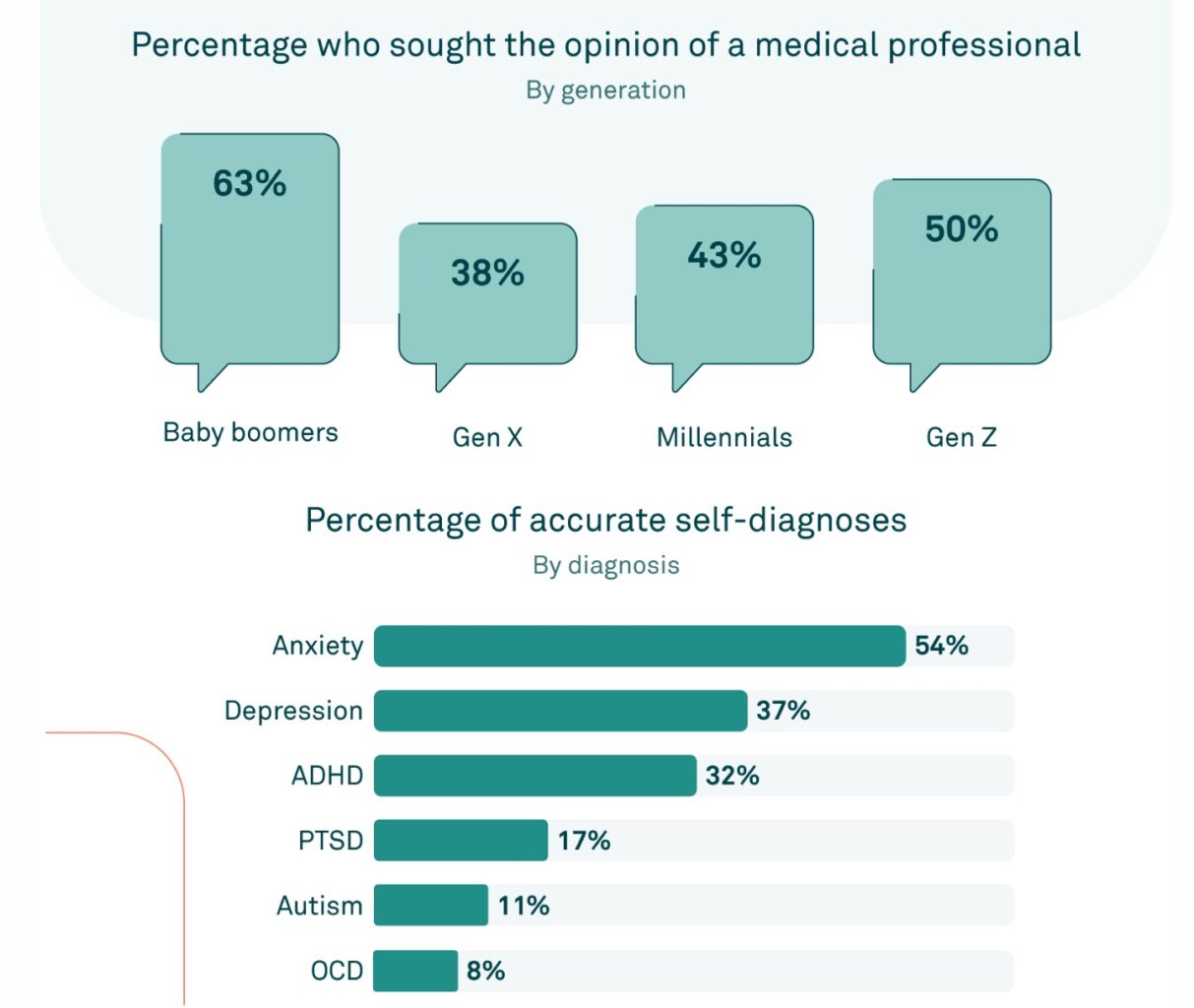

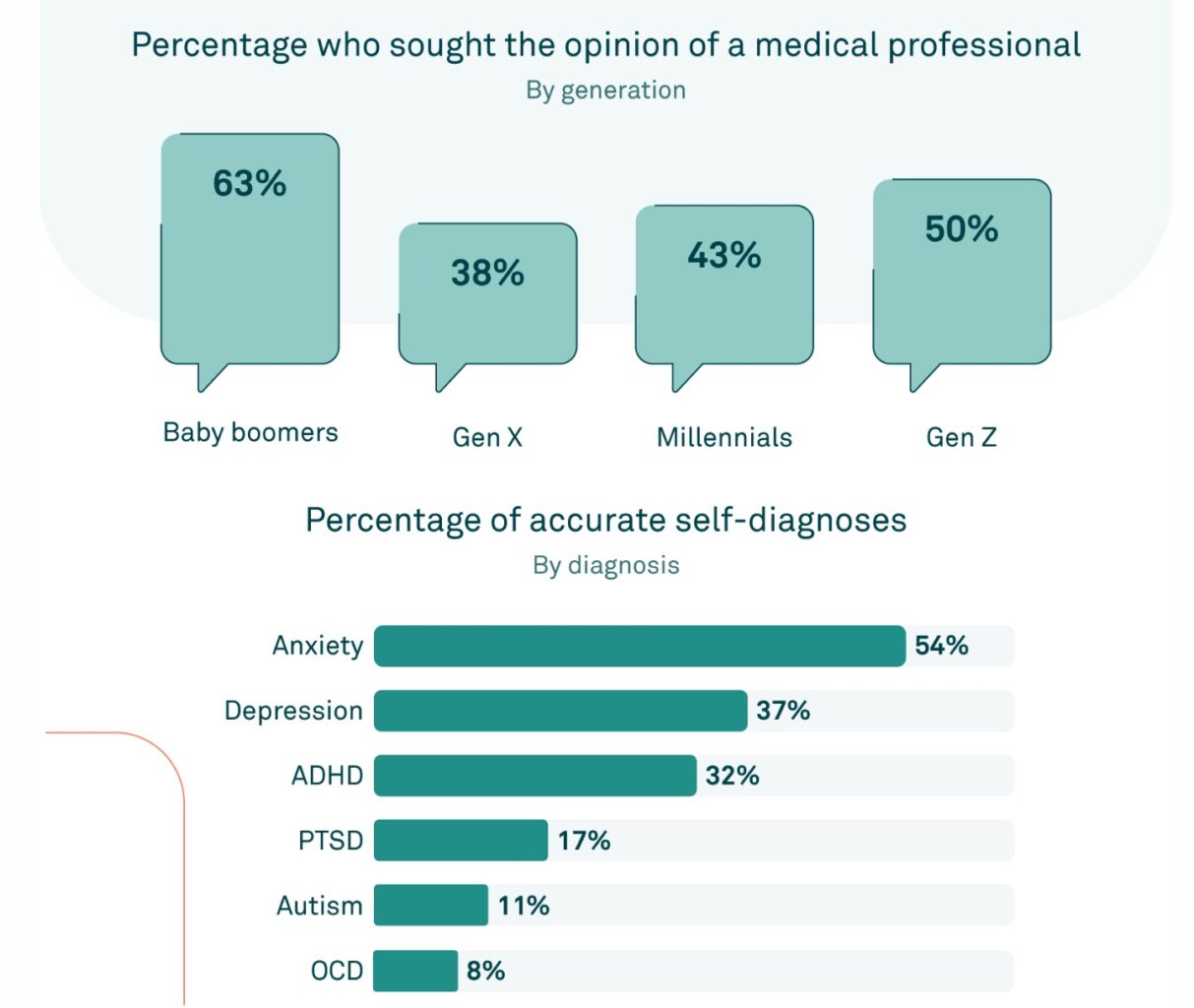

The survey showed that even when people believed they had some kind of mental health issue, it did not always motivate them to seek help.

Less than half of all respondents who self-diagnosed followed up with a medical professional about a disease or illness they discovered on social media. That said, it’s worth factoring in the additional cost of expensive therapy sessions or private healthcare visits, which may prevent many participants from doing so.

Of those that did seek professional advice, 82 percent had their self-diagnosed concerns confirmed. The survey also found that 32 percent of these individuals went on to start medication or treatment.

Considering this result, it may seem like health-related content on social media has been beneficial and enlightening for those who asked for help from medical professionals.

But interestingly, the vast majority of participants recognised that this type of content may be doing equally as much harm as it is good.

Pros and cons of medical-related content

Of course, there is much speculation surrounding the self-fulfilling prophecy of discovering that disorders exist and relating them back to your own behaviours.

We’ve written about this phenomenon before, when TikTok began connecting trivial and common quirks with various mental health diagnoses ranging from common disorders to extremely rare ones.

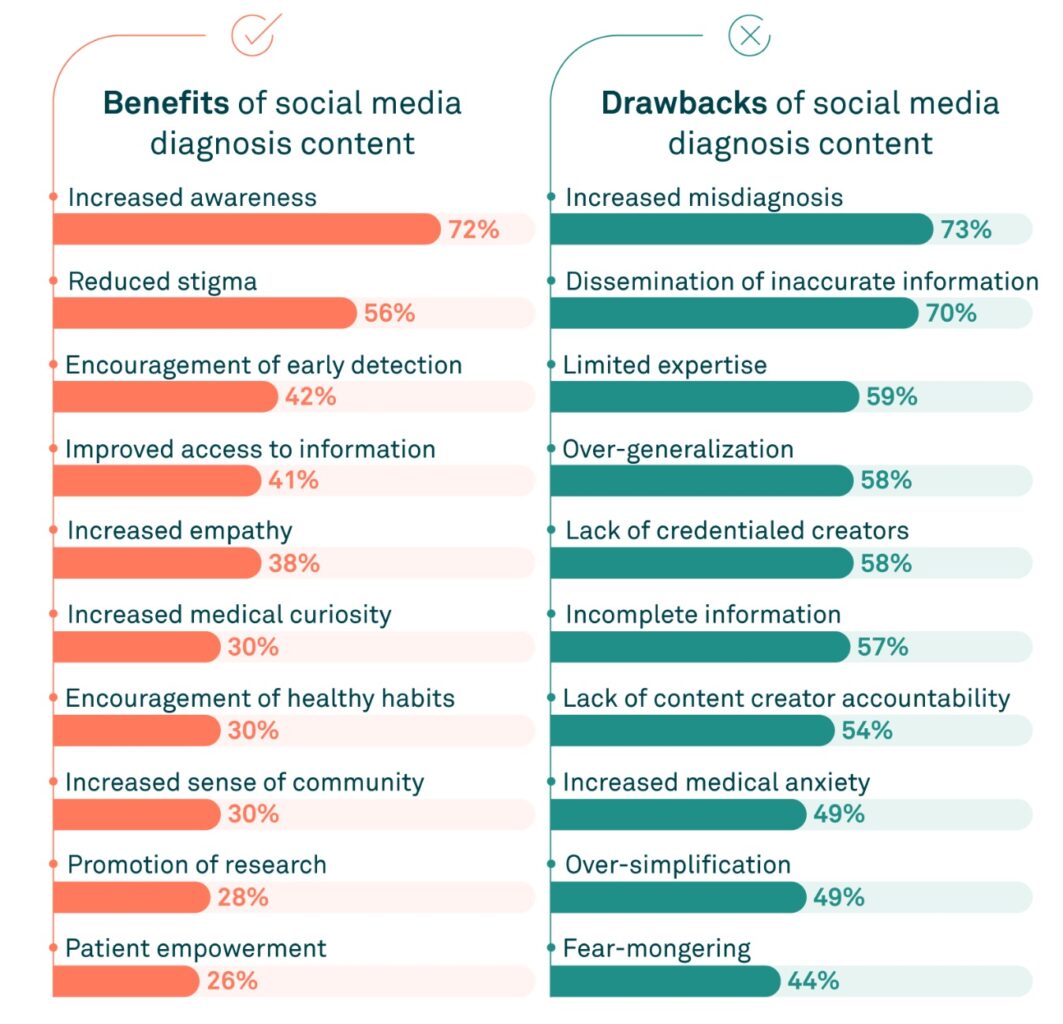

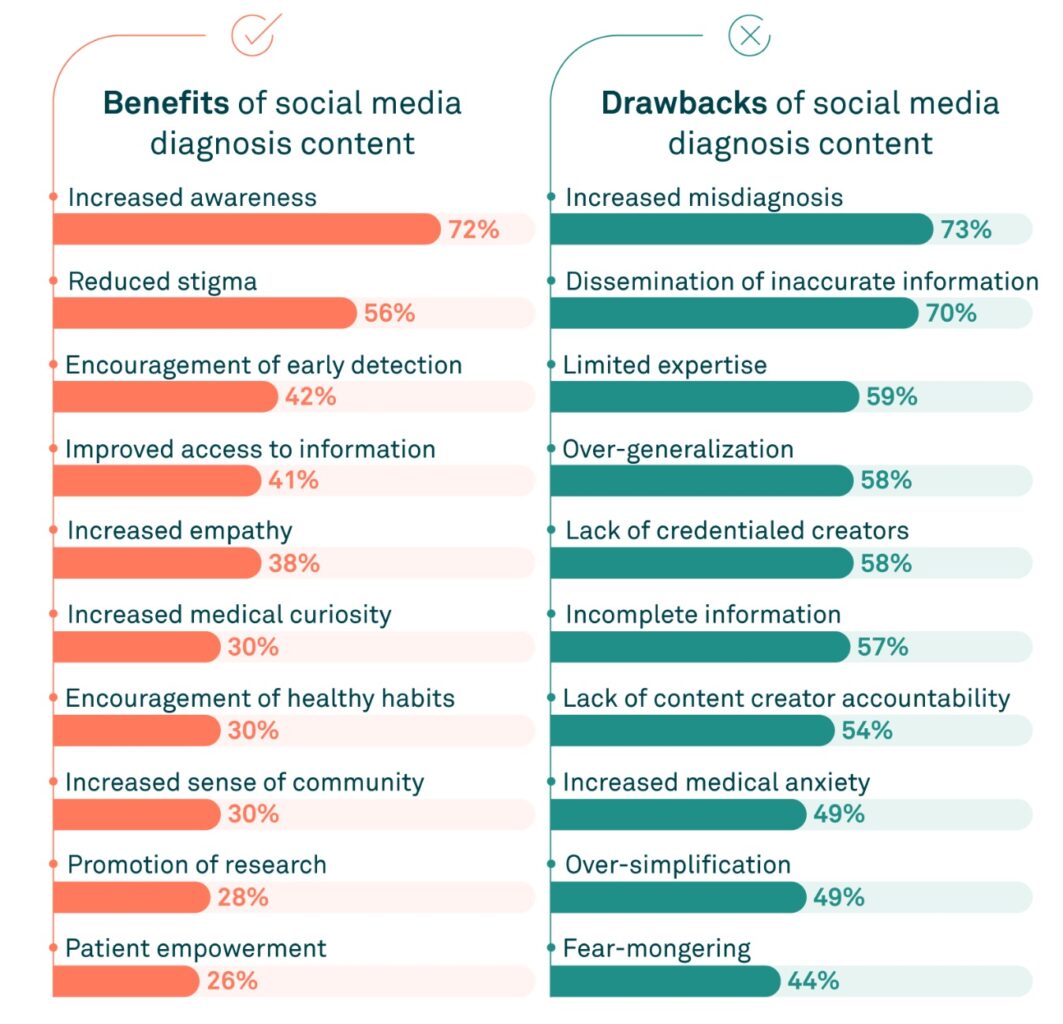

Although the majority of those surveyed agreed that health-related content on social media led to greater awareness and reduced stigma surrounding mental health issues, less than half agreed that it led to early detection of illness or improved accessibility to accurate information.

Most did not believe that being exposed to this health-related digital content encouraged the cultivation of healthier habits, nor did they believe it fostered empathy or a sense of community.

Surprisingly, respondents expressed additional worries about viewing medical content online.

Their primary concerns lay with the accuracy of what they had learned, the possibility of misdiagnosis, as well as fear-mongering and a lack of accountability held by those creating the content.

A massive 88 percent of respondents said that warning statements should be applied to digital content that is not produced by medical professionals.

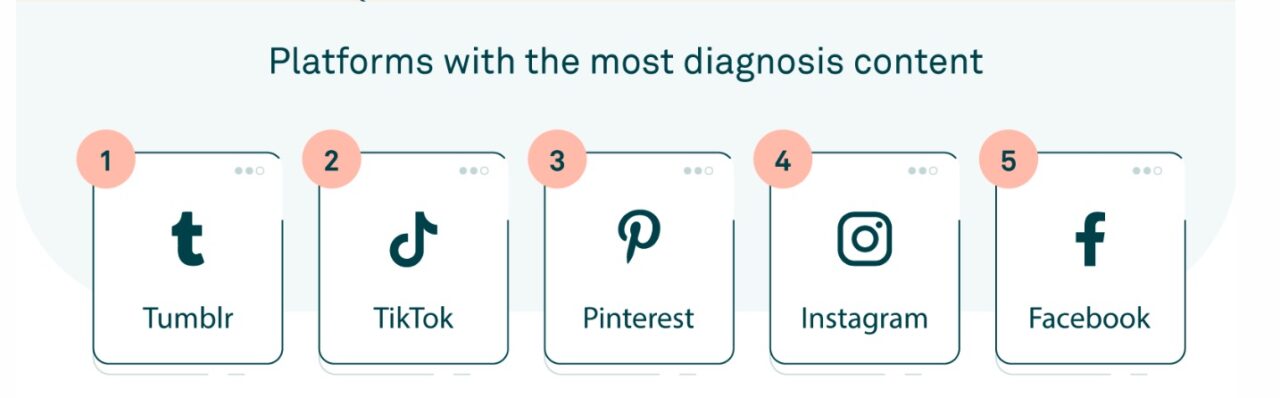

As the #mentalhealth corner of TikTok amasses 95.4 billion views and counting, other researchers have started weighing in on how much of this tremendously abundant advice is legitimate.

Upon analysing 500 videos tagged on the subject, experts found that 83.7 percent of mental health advice on TikTok is ‘misleading,’ while 14.2 percent of videos include content that could be ‘potentially damaging’.

It also found that a mere 9 percent of those offering guidance on the platform had relevant medical qualifications in the respective field of their chosen topic. Only 1 percent of creators who weren’t qualified professionals had explicitly stated that fact somewhere in the caption or clip.

In conclusion

In this ultra-digital age, are constantly reminded that we shouldn’t believe everything we see online. We hear it time and time again – sometimes straight from the horses’ mouths.

Influencers, micro-celebrities, and those interested in improving media literacy tell us that what we see on social media doesn’t always grant us the understanding provided by the full picture.

This way of thinking, though sometimes difficult to remember in hard times, should also be applied to health-related content we see on social media.

The conflicted responses about the pros and cons of this content – as well as the level of self-diagnosis occurring across every generation after being exposed to it – is something we should be keeping an eye on.

In the future, it may be a good idea for social media companies to place fact-checking data points to avoid misinformation and non-credible claims made by creators online.

This could require any creator making broad medical claims to provide proof of their credentials. Or something as simple and similar as the fact-checking system now implemented on Elon Musk’s Twitter / X / whatever it’s called these days.

Because while it’s true that mental health struggles are on the rise, everyone is completely unique. When struggling, we should sparsely rely on people we don’t know online for clinical advice – whether they claim to be experts or not.

Studies continue to point to social media itself as a primary culprit for conjuring up negative self-image, anxiety, and depression in young people.

So perhaps the greatest advice would be to get offline from time to time – and when we’re logged in… to take everything we see with a grain of salt.