We spoke with award-winning filmmaker and dedicated animal rights activist Rebecca Cappelli about the far-reaching culture shift she hopes to bring about with her latest documentary, Slay.

Every year, billions of animals are killed so that their fur, wool, and skin can be passed on to the fashion industry.

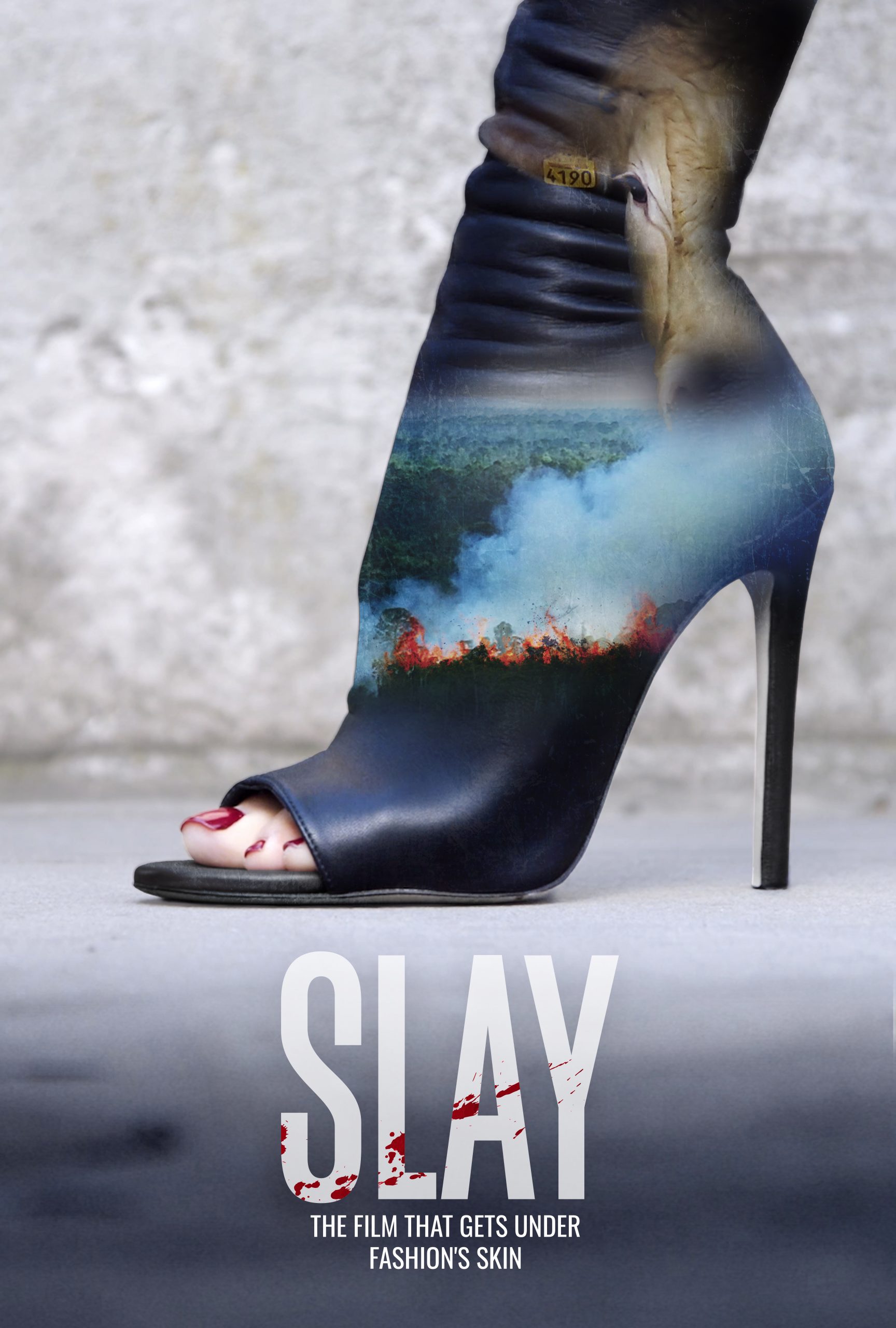

Lining the shelves of luxury ateliers and designer stores around the world as bags, coats, shoes, and other accessories, the presence of animal products has become so commonplace that we rarely stop to think about how they got there in the first place.

This harmful practice thrives not because the process of raising animals, slaughtering them, and transforming their remains into fabric is discreet, but because our understanding of how they become these materials has been eliminated almost entirely from public consciousness.

A concerning lack of information on the subject has caused a collective apathy that prevents widespread outrage, no matter how many barriers are knocked down by rights activists.

Decades spent distancing ourselves has allowed animal abuse to flourish, negatively affecting people and planet in tangent.

After all, if we were forced to actively source animal products first hand, we likely wouldn’t dream of wearing another garment of this nature again.

Award-winning filmmaker Rebecca Cappelli, the brains behind a new and unmissable documentary titled Slay, wants us to take a long hard look at how we dress and change our behaviours for good.

How did Rebecca first become aware of fashion’s animal problem?

While living in Shanghai, Rebecca rescued a puppy destined to be slain for his meat and fur.

Sitting at home with her new furry friend, Oneida, she could not ignore the looming presence of her own leather-filled, fur-accented closet in the next room over.

In this moment, her perspective of her own choices and the practices of the fashion industry itself had shifted irreversibly. Almost immediately, Rebecca embarked upon a journey to discover where and how animals are raised, killed, and eventually made into clothing.

Without detailed information on the sites she was scouring, however, all searches eventually led to a dead end and the story of how living, breathing creatures reach the stage of being worn by millions remained incomplete.

Dissatisfied with the ambiguous data available, she started making phone calls to the offices of fashion houses that would point her to factories located across Europe, India, and China.

Alongside her extensive online research – which was vital to leveraging Slay and evidently required Rebecca to go to great lengths to acquire it – this would prove invaluable as she began peeling back the layers.

Accompanied by a small film crew for her unscripted documentary, she was astonished by how easy it was to gain access to these locations, especially given how vague brands had been about where their animal-based products really came from.

This is when it became obvious that the animal trade in fashion had serious implications for all life on the planet – entire ecosystems, the animals within them, and the communities whose livelihoods depend on the industry.

‘I think I went in with a little bit of naivety about the topic, I thought it would be simple to cover,’ she tells Thred.

‘I didn’t realise how deep it would go. I couldn’t predict what I would discover during the process. We didn’t spend months trying to find these problems, however. They were right there in front of us.’

How does Slay tackle such a contentious and wide-reaching topic?

Rebecca made sure to highlight the intrinsic connection between animals, us, and the environment throughout Slay, striving to push for wider recognition from both the industry and consumers.

‘Justice should not be exclusive or have limits,’ she says. ‘It is for all. An industry practice that harms the environment is equally harmful for animals and people. Harm goes hand-in-hand with harm. The objective with Slay is to include all three in the equation of bringing about change.’

To get this message across, Rebecca lifts the curtain on fashion’s treatment of cows, foxes, and sheep, among others, choosing to explore the environmental implications of their trade and the vulnerable communities involved in processes like tanning.

Rebecca believes our disconnect comes from a lack of knowledge on these processes. Most of us don’t fully appreciate how the products we wear reach shop floors.

From the mass deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, to clearing space for cattle farms, to the ill health of workers regularly handling toxic chemicals so we can be assured of safe clothing, no stone was left unturned.

‘Slay covers a lot,’ continues Rebecca. ‘Seven countries, three major industries, as well as human, environmental, and animal rights issues.’

Tackling so much content presents an obvious question. How did Rebecca ensure an audience response that didn’t invoke defeatism and inaction, particularly with a subject as far-reaching (and for decades, impervious) as this one?

She ensured that the problems discussed weren’t presented in an immense or overwhelming way, as this could diminish the effectiveness of Slay’s call-to-action. She also acknowledges that successful storytelling has to combine empathy with cited truth, balancing both during the film’s 85-minute runtime.

‘Losing the audience was a key concern of ours,’ she explains.

‘Our ability to process data varies. In addition to encouraging emotional connections, I sought to be really fact-based across the board to guarantee that viewers would be able to channel their intellectual intelligence as well.’