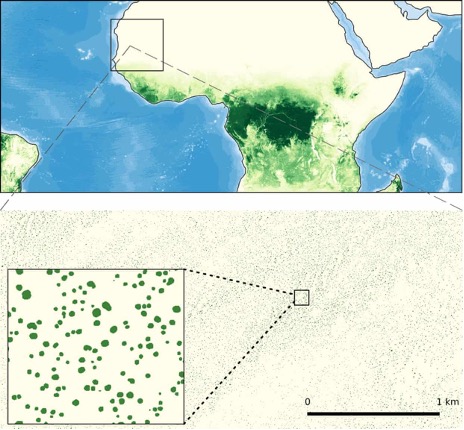

A new method of mapping the location and size of trees growing in arid and semi-arid regions is laying the groundwork for a more accurate global measurement of carbon storage on land.

According to a recent study that combines Artificial Intelligence with detailed satellite imagery, there are in fact far more trees in the West African Sahara Desert than you may expect.

This is all thanks to Nasa (who else, of course) which recently unveiled a revolutionary new method of mapping the Earth’s trees that’s set to dramatically change our understanding of the planet’s health in years to come.

Though efforts to keep our planet’s arboreal accounts accurate have been on a rapid upward trajectory as of late, they haven’t been all that successful in contributing to our limited knowledge of how many trees there actually are.

This is because a significant portion of the Earth remains inaccessible either due to war, ownership, or geography. While satellite imagery is the most-used tool for collecting data of this kind, trees that aren’t relatively easy to spot from space (e.g. those in forests) are often overlooked.

Here to change that are a group of researchers fronted by Martin Brandt, Assistant Professor of Geography at the University of Copenhagen, who collaborated with Nasa’s Goddard Space Centre.

They were granted access to DigitalGlobe’s satellite cameras which have only previously been available to commercial entities. When used in arid and semi-arid locations, these cameras capture images of a high enough resolution to make out individual trees and measure their crown size. It promises a much more accurate picture in the future than the 2009 global estimate of there being 400bn trees and 3tn just six years later (an enormous jump to say the least).

Using this raft of more sophisticated monitoring resources as well as one of the world’s most powerful supercomputers to count every tree in a large swathe of the Sahara (a process that took mere hours), this method is laying the groundwork for a more accurate global measurement of carbon storage on land.

Though the area had previously registered as having little to no tree coverage and the expectations of international scientists were modest, the results were pleasantly surprising.

Roughly 10% of the Sahara ‘where no one would expect to find many trees’ actually had ‘quite a few hundred million’ as stated by Brandt. It’s the first time anyone has counted trees across a dryland region of this size.

‘Up until now, most people thought that virtually none existed,’ he adds. ‘We counted hundreds of millions of trees in the desert alone. Doing so wouldn’t have been possible without this technology. Indeed, I think it marks the beginning of a new scientific era.’