Already, you may be echoing the thoughts of many Twitter users who have called Freeman’s captives gullible. After all, would an MI5 agent really admit they’re a spy to three random strangers?

While this is a valid question, for which the answer is realistically no, this true story exhibits how vulnerable people can become when subjected to coercive control and a believed threat to their personal safety.

Rather than being a source of entertainment, The Puppet Master does an important job of illustrating to the public how anyone could fall victim to both psychological and physical entrapment once a certain level of fear, trust, or even love is fostered between an individual and their perpetrator.

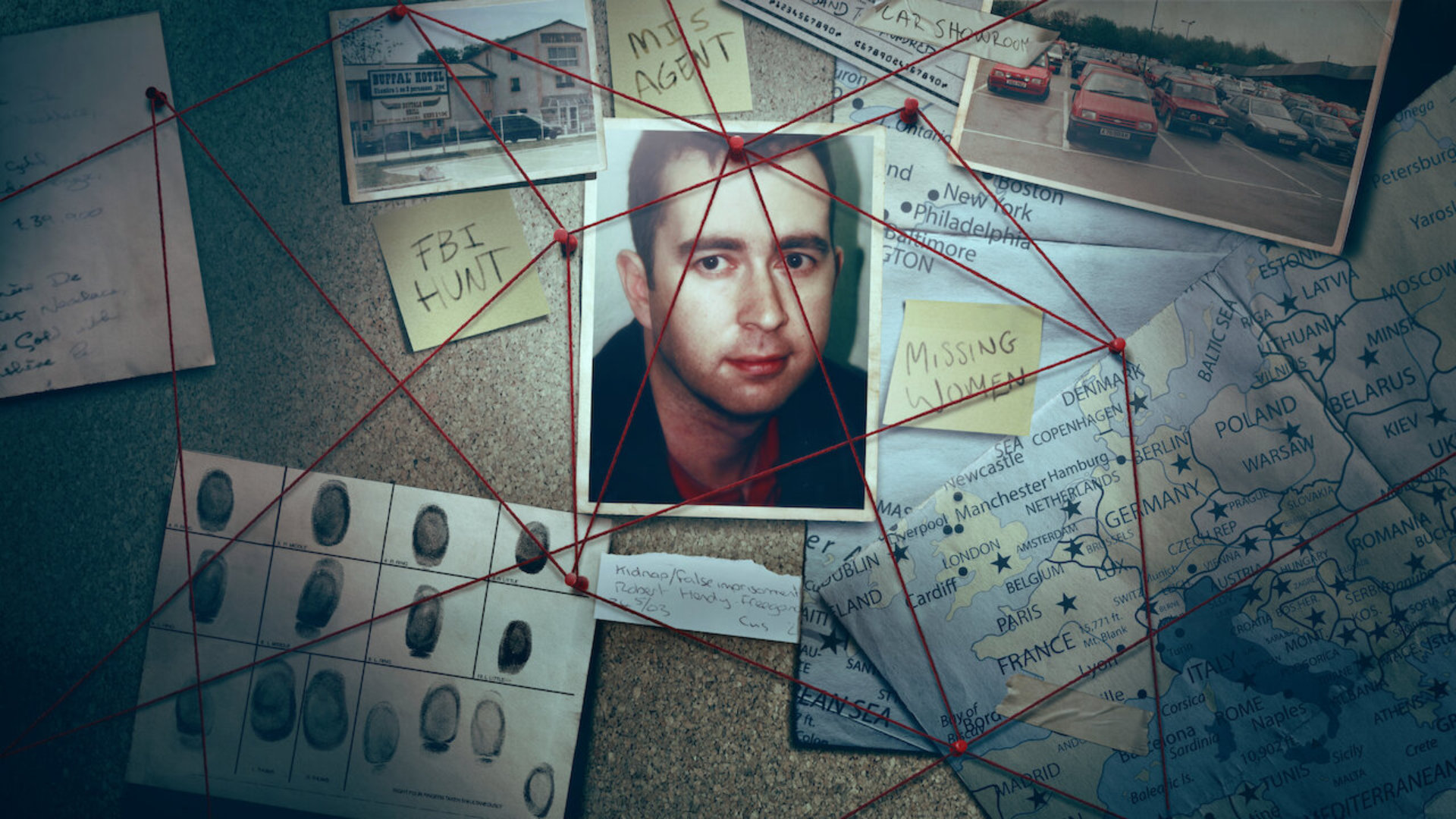

Using these very methods, Freegard’s intricate web of lies and threats kept one victim, Sarah Smith, under his thumb for a decade.

Sarah was forced to use a pseudonym, to change her appearance, and have her daily activities monitored. She also had contact with family reduced strictly to phone requests for money, amounts which were ultimately pocketed by Freegard.

In 2002, real MI5 detectives located Sarah after gaining contact with several other women who had fallen victim to Freegard’s deceit. The elusive conman was then arrested and charged with fraud and kidnapping.

In this moment, an official understanding of the detriment caused by inducing prolonged fear and psychological distress in another individual would have classified Freegard’s actions as a criminal act – but the story unfolded differently.

Just two years after his arrest, Freegard appealed his kidnapping charge on the basis that he had not physically restrained his captives from leaving. Freegard’s lawyer argued that, at any moment, Sarah and the other victims could have gotten up and left the safehouses they were persuaded to stay in.

Kidnapping was Freegard’s most serious offence and would have granted him life in prison, but following this appeal the charge was dropped. Serving time only for fraud, he was released in 2009.

It’s true, Robert Freegard would have been sentenced differently according to today’s legal system. Coercive control and its ability to psychologically (and physically) paralyze victims has been considered a criminal act in the UK since 2015, thanks to a successful campaign run by Women’s Aid.

Acts of coercive control include: unreasonable demands, degradation, restricting daily activities, threats or intimidation, financial control, monitoring of time, isolation, restricted mobility, and food deprivation – all of which were carried out by Freegard.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XA2xypdKja4&ab_channel=SoapsNews

It’s also worth noting that Freegard had sexually coerced two of his victims when they were in serious states of psychological distress, entrapment, and deprivation. According to legislation at the time, though, these instances were considered consensual.

Had current laws been in place, Freegard wouldn’t have gone on to date Sandra Clifton, a mother of two children, under the false name David in 2013. Now teenagers, Jake and Sophie recount on screen how ‘David’ had forced their family apart and isolated their mother from everyone in her life but him.

To this day, Sandra is still believed to be living under the radar with Freegard and has halted communication with her two teenagers entirely. She also claims that she is happy and aware of the true identity of ‘David’.

In 2019, over 17,600 offences of coercive control were recorded by police. Women’s Aid also reports that 95 percent of coercive control victims are women, with 74 percent of perpetrators being men.

So, The Puppet Master might tell an interesting tale of fraud and deception, but it also highlights how important psychological research and knowledge about mental health truly are into creating adequate frameworks for the law.

Thankfully, our updated understanding of the psychological impacts of controlling behaviour has led to stronger legislation and harsher punishments for those exhibiting them – if only victims are able to report them as such.