As Gen Z continues to challenge the established status quo toward finances, sexuality, and capitalism, why are we still so fixated on the age-old concept of ‘finding the one’?

We often hear that Gen-Z is the generation of individualism.

While they’re often criticised for this heightened sense of self, it could be argued that Gen-Z is the first generation to spend time thinking about what they really want. In fact, Gen-Z has become so politically and digitally empowered that they regularly challenge the status quo with rigid confidence.

Gen-Z has strayed so far away from tradition and what they were bought up to believe, that they’re redefining everything from their careers to their future goals and finances.

Why is it, then, that societal ideals about relationships feel like they’re lagging behind?

Millennials and Gen-Z have shown a greater acceptance for fluid relationship dynamics, such as polyamory, pansexualism, and even thruples. While these conversations on structures and sexuality are thriving, many of us are still feeling pressured by the lifelong quest to find the ‘one’.

In fact, in a survey conducted by the dating app Happn, 32% of millennials and Gen-Z said they were looking for marriage in 2022.

It wasn’t until the beginning of this year that I realised my own search for the ‘one’ had been a subconscious motivation for all my relationships, whether casual, serious, or sexual.

When my last relationship ended, I started dating like it was my full-time job. If any date fell short of amazing, I went back to the drawing board and moved straight onto the next potential suitor, a futile effort to seek out an idealised, perfect person who could be the ‘one’.

I describe looking for the ‘one’ as futile because, put simply, it doesn’t exist. It was only when others pointed it out to me that I was fully able to understand and realise where I was going wrong.

Dolly Alderton’s writing first prompted me to reconsider the way I, and our entire generation, think about relationships. Specifically, her novels Everything I Know About Love and Ghosts taught me that if you spend your whole life searching, you stop noticing the things that are already there.

Many of us are already surrounded by love in the form of deep and powerful friendships, but we’re so transfixed by searching for the ‘one’ that we overlook these meaningful connections.

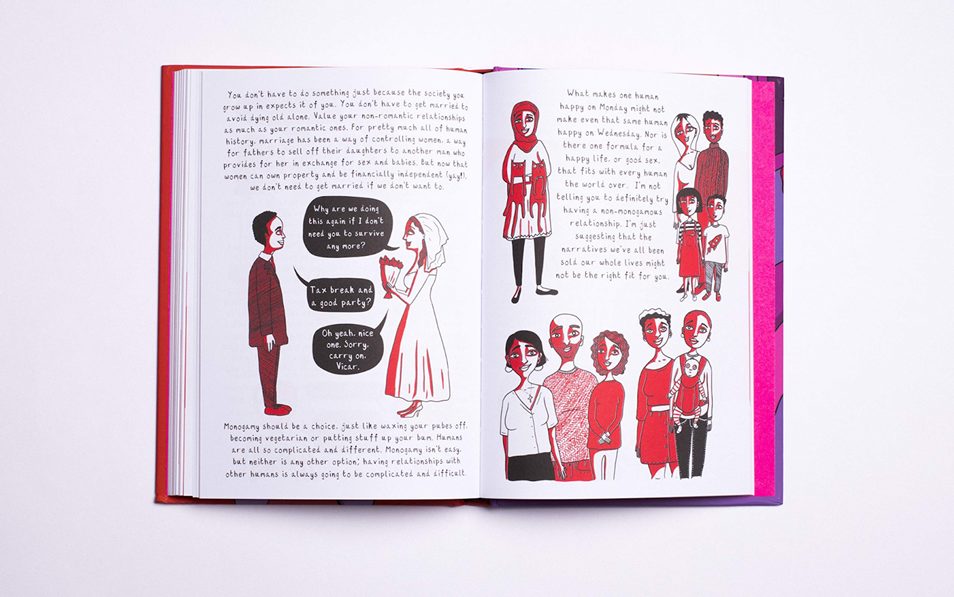

Flo Perry delves into this topic further in her book How to Have Feminist Sex, stating that, ‘you don’t have to do something just because the society you grow up in expects it of you… Value your non-romantic relationships as much as your romantic ones.’