The show’s male contestants have repeatedly bullied, belittled, and gaslit. On a show plagued by mental health crises and online abuse, how thin is the line between entertainment and intervention?

I love staying in the loop. Maybe it’s the nature of my job, but keeping up with current affairs is a major part of my daily routine. That might mean reading the newspaper or listening to The Rest is Politics on my morning commute. But it also means watching Love Island every night.

I’m not ashamed to admit that I love this show; the drama, the game playing, the aimless parties in which contestants get dressed to the nines just to sit in the garden and sip 0% WKD from plastic cups.

But this year, the glitz and the camp of this beloved reality series is starting to wane. Granted, the latest season has pulled Love Island UK back from the edge of irrelevance. Viewership is at a high, there’s endless arguing and recoupling and infidelity (the recipe for great reality TV), and most of the contestants have standout personalities – something many would say has been lacking in recent years.

But this cacophony of melodrama isn’t fulfilling my weeknights quite as I’d like it to. I feel increasingly bitter watching the love triangles unfold and the youngest contestants (namely Shakira) repeatedly break down over the behavior of other islanders.

It’s hard not to feel concerned for these individuals, given the Love Island’s history. Two former contestants, Mike Thalassitis and Sophie Gradon, both died by suicide after appearing on the show. And in 2020, show host Caroline Flack also ended her own life following relentless online trolling.

Since these tragic deaths, ITV has vowed to implement a more stringent duty of care for those involved. Contestants are usually young, impressionable, and seeking fame. For many, love is just an added bonus.

It’s this knowledge that gives viewers a sense of entitlement when it comes to belittling and mocking those on the show. After all, they chose to do this – knowing full well how Love Island’s toxic format (designed to pit islanders against one another for audience entertainment) and life-altering aftermath (having been shut off from the outside world for weeks, contestants leave the show to a newfound platform and widespread public scrutiny) has impacted those who sign up for it.

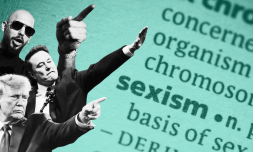

Years later, and nothing has changed. Love Island producers continue to ignore the recurring misogynistic behaviour of male contestants toward female contestants. How many more Ofcom complaints and statements from Women’s Aid will it take for them to take it seriously? pic.twitter.com/gvj51w9BA1

— 𝕷🍒 (@imavenusgirl) July 21, 2025

But is this really a valid argument? The biggest thing I feel when watching this new season of the show is a sense of hypocrisy. I feel for the young women crying on my screen as a group of sub-par men repeatedly gaslight them. But here I am, tuning in every night to see what happens next. It’s my viewership that has ultimately given these men the platform from which they’re behaving so terribly.

Love Island has always received Ofcom complaints, given its sexualised nature and run-of-the-mill reality format. But this year the regulatory board has received an unprecedented number of calls about ‘misogynistic’ and ‘bullying’ behaviour.

At the center of the storm was Harrison Solomon, 22 – an English footballer based in Miami who had been dating Lauren Wood, 26, since returning from Casa Amour. Harrison outraged viewers and fellow islanders when he slept with Lauren and then proceeded to couple up with former flame Toni Laites, despite telling Lauren things were over between them.