The term recently made an impact within the UK legal system, speaking to a wider and long overdue culture shift in challenging abusive behaviour.

If you’ve ever dipped your toe into the dating pool, likelihood is you may have experienced ‘gaslighting’ at one stage or another.

The term, which was in fact being used colloquially as early as the 60s but only recently began to gain traction in mainstream conversation thanks to social media, refers to an insidious form of psychological manipulation that drives someone to question their own reality.

It’s achieved – with the ultimate goal of giving the perpetrator a monopoly on truth – by undermining and trivialising the victim’s memories, feelings, and needs, as well as refuting basic facts, reliable sources of information, or the environment around them.

According to a 2018 policing report, 95% of those affected are women.

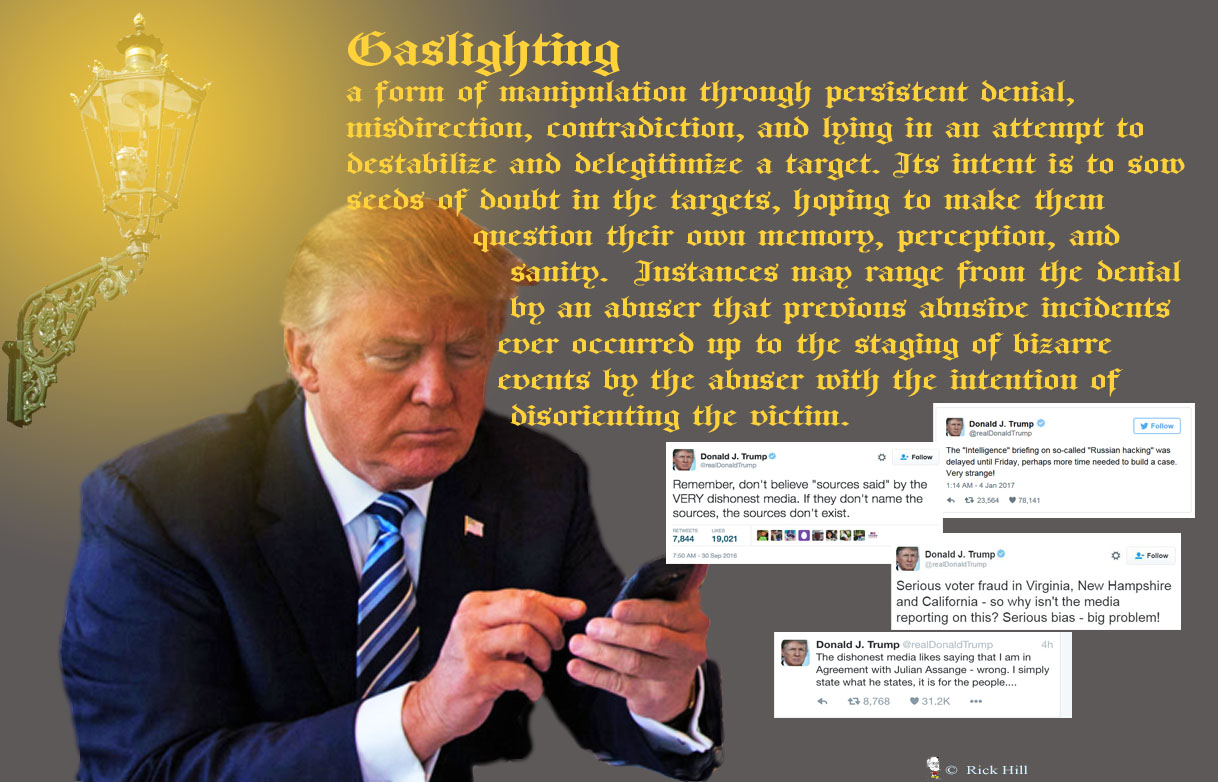

Now, if this sounds familiar outside of a relationship context, it’s because throughout Trump’s administration, the former president of the United States made several headlines for leading a sustained campaign of political gaslighting, using it to make voters doubt their recollection of his past actions.

It’s arguably for this reason that the phrase seeped so far into our vernacular at the rate it did, named one of the Oxford English Dictionary’s most popular words of 2018.

In the years since, however, it’s undergone what experts call ‘semantic drift,’ whereby its meaning has morphed over time as it permeates popular culture.

The latest examples of this being Love Island contestants playing out the textbook tactic on live television and West Elm Caleb, an alleged ‘serial dater,’ who was publicly condemned on TikTok for ghosting the multiple women he’d been seeing simultaneously.

At its core, gaslighting is a type of coercive control that forces victims to distrust their very sense of self, gradually eroding their agency in a bid to make them isolated, dependent, and vulnerable to further exploitation.

By feeding someone false narratives and challenging their beliefs, abusers are able to keep their targets in a chronic state of uncertainty and influence their mental state for their own personal gain.

‘Obviously, in this situation you feel like everything is your fault and that, if you do things exactly right, you can manage the behaviour of your abuser,’ a counsellor who works with survivors of domestic violence told i-D.

‘There’s an automatic power imbalance in an emotionally abusive relationship and gaslighting causes that too. By convincing the other person that their perception of reality is wrong, it immediately makes them feel childlike and helpless. Which is what it’s designed for.’

This is why it’s a great deal harder to pinpoint gaslighting than physical abuse (which is less subject to interpretation) because the victim will rarely want to come forward about an issue even they themselves have little clarity on.

And every relationship has its moments of conflict, after all.