Months after Sarah Everard’s murder, the government has introduced new measures to ensure female safety. This may sound promising, but will it make a difference?

Earlier this year, upon hearing of Sarah Everard’s disappearance, I wrote that more needed to be done to protect womxn everywhere.

Her case not only provoked a potent reaction across the globe but unearthed far broader concerns regarding the abuse and violence we face on a daily basis.

This was reinforced by an ensuing survey which saw 97% of British womxn aged 18-24 report being subjected to sexual harassment in their lifetimes.

It also confirmed what most of us already knew: that we were long-overdue a fundamental culture shift to ensure our safety, one that no longer relies on us to stay mindful of the danger we face and modify our behaviour to avoid it.

In March, efforts to address the issue showed potential when the government announced it would ask police to make records of whether or not a crime had been motivated by a person’s sex or gender on an ‘experimental basis’.

It appeared to be a response to public outcry, a genuine attempt to guarantee that womxn could come forward with more confidence.

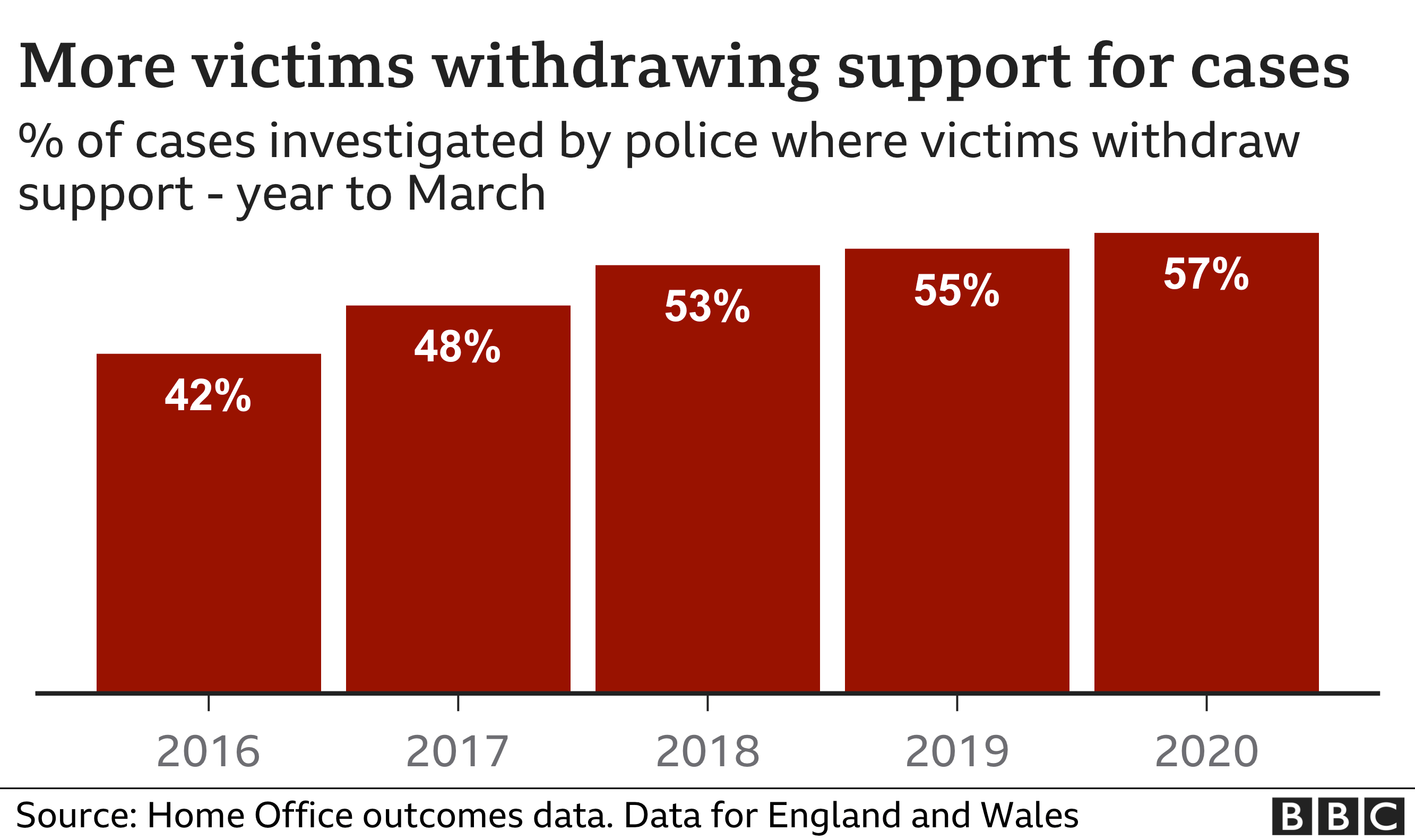

Unfortunately, we’ve yet to see any real world changes as a result of this initiative, and many have since acknowledged that it doesn’t automatically guarantee greater effectiveness at bringing justice to offenders. Several months later, however, and it seems we could be nearing legitimate progress.

Part of the country’s eagerly anticipated plan to tackle violence against womxn, cyber flashing (the sending of images or video recordings of genitals over peer-to-peer Wi-Fi networks) and public street harassment (PSH) may be criminalised.

‘I am determined to give the police the powers they need to crack down on perpetrators and carry out their duties to protect the public whilst providing victims with the care and support they deserve,’ announced home secretary Priti Patel. ‘We will be reviewing gaps in existing law.’

Shaped by 180,000 testimonies from survivors, the £5m strategy also sets out a pledge to appoint so-called ‘Violence Against Womxn Transport Champions’ to ‘drive forward positive change and tackle the problems faced by female passengers on public transport.’

It’s additionally offering a 24hr rape helpline and pilot tool called StreetSafe whereby users can record the areas they feel unsafe for better protections, such as extra streetlights or surveillance cameras.

But will this really make a difference?

What prompted the measures and what do they involve?

Last week, the Law Commission published a report arguing that laws in this sphere ‘are not working as well as they should’ and are unsuccessful in prohibiting genuinely harmful conduct.

With regards to cyber flashing, authors urged policymakers to consider adding it to the Sexual Offences Act 2003, which up until this point has put those found guilty of indecent exposure offline at risk of getting two years in prison and being placed on the sex offenders register.

The same rules do not currently apply to perpetrators who do this online. This is what the legal reform watchdog is seeking to alter.

New laws would protect victims from receiving unsolicited ‘dick pics’ on any kind of digital platform, such as AirDrop, Snapchat, and via DMs. Anything sent without prior consent and with the intention of causing alarm, stress, or humiliation would be included.

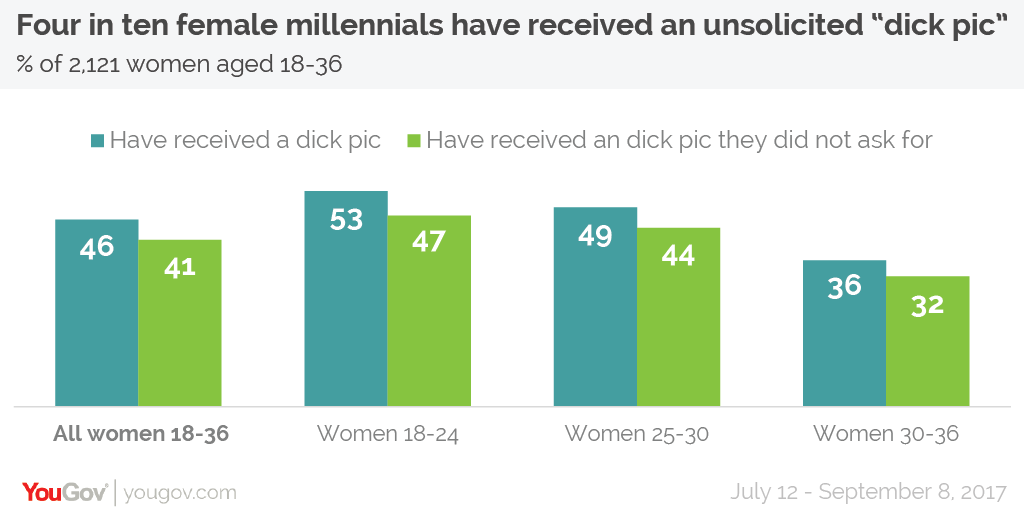

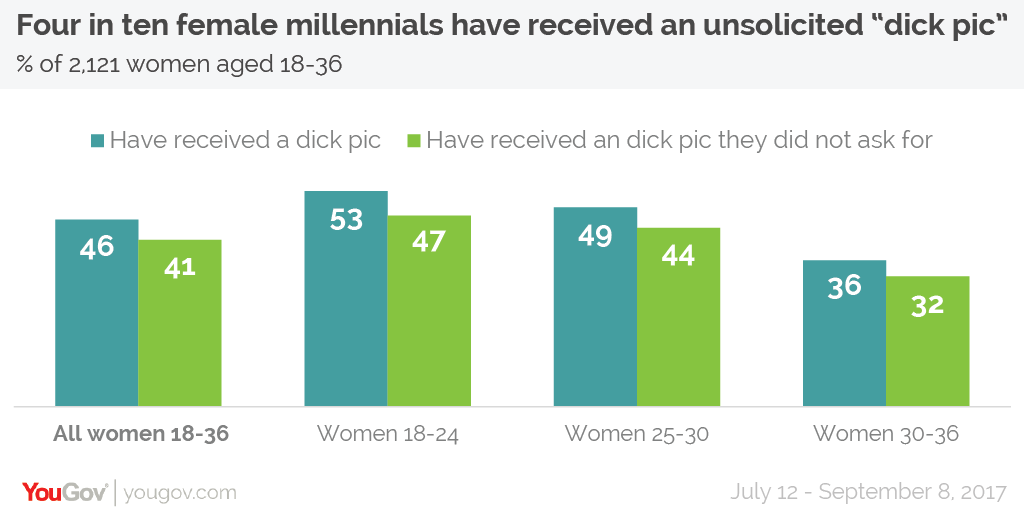

To contextualise, a 2018 YouGov poll uncovered that four in ten female millennials have experienced this and, more recently, 90% of schoolgirls reported the same to Ofsted.

An especially rampant problem on dating apps and social media, it gives the recipient the ‘twofold threat of an unidentifiable sender who’s also proximate,’ writes Sophia Ankel.

‘With technology infiltrating every aspect of our private lives, this unwelcome input from male strangers has become so normal that it is frequently ignored and brushed off and, in some cases, even laughed about.’

‘But it’s not a joke, it’s a psychological violation and cannot be tolerated or normalised.’