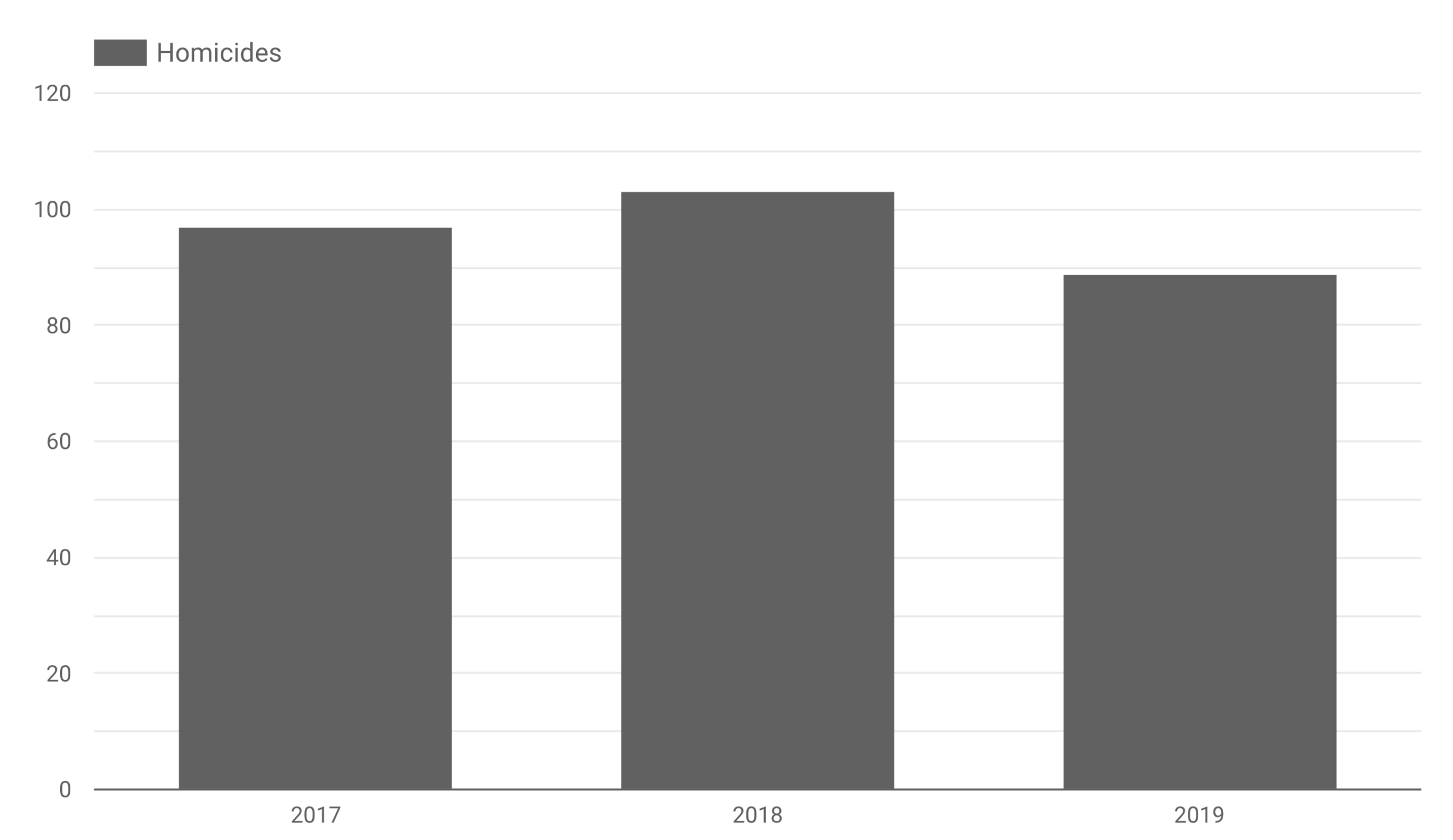

A local human rights group has revealed that Colombia’s police are responsible for 289 homicides committed between 2017 and 2019, for which only two policemen have been convicted.

In September last year, a video of police in the Colombian capital of Bogotá attacking and tazing father of two Javier Ordóñez began circulating on social media. He was later beaten to death in police custody.

Throughout the following months, the event would go on to trigger a wave of protests against police brutality across the country, amounting to the killings of 13 protestors at the hands of law enforcement.

According to a recent report by local human rights group Temblores, Colombia’s police are currently responsible for 289 homicides that took place between 2017 and 2019, for which only two policemen have been convicted.

The NGO’s Police Violence Observatory obtained the information from the Medical Examiner’s Office, which determines people’s cause of death and reveals that police are to blame for the staggering 45% of murders committed by Colombia’s security forces.

‘The police committed one murder every 3.8 days and almost two murders per week,’ explains the report, which concludes that police killings are a consistent occurrence and that the apparent negligence in legal action leaves a lot of questions about the lawfulness of the police’s use of lethal force.

‘It is necessary to ask ourselves why such high numbers of homicides are committed: are they the result of malicious behaviour? Are they the result of disproportionate use of force?’

Despite the ongoing and undeniably prevalent issue of police brutality however, Colombia’s unrest goes far beyond this, and indignation was rife well before the video of the Ordóñez incident went viral.

At present, Colombia is one of the most unequal countries in the world, facing an ever-growing gulf between its middle to upper class urban elite and neglected rural areas, which lack basic services such as healthcare and potable water. Recently, the majority of its stateless regions have fallen under the control of armed groups, with the thousands of displaced people fleeing this conflict now living on city margins.

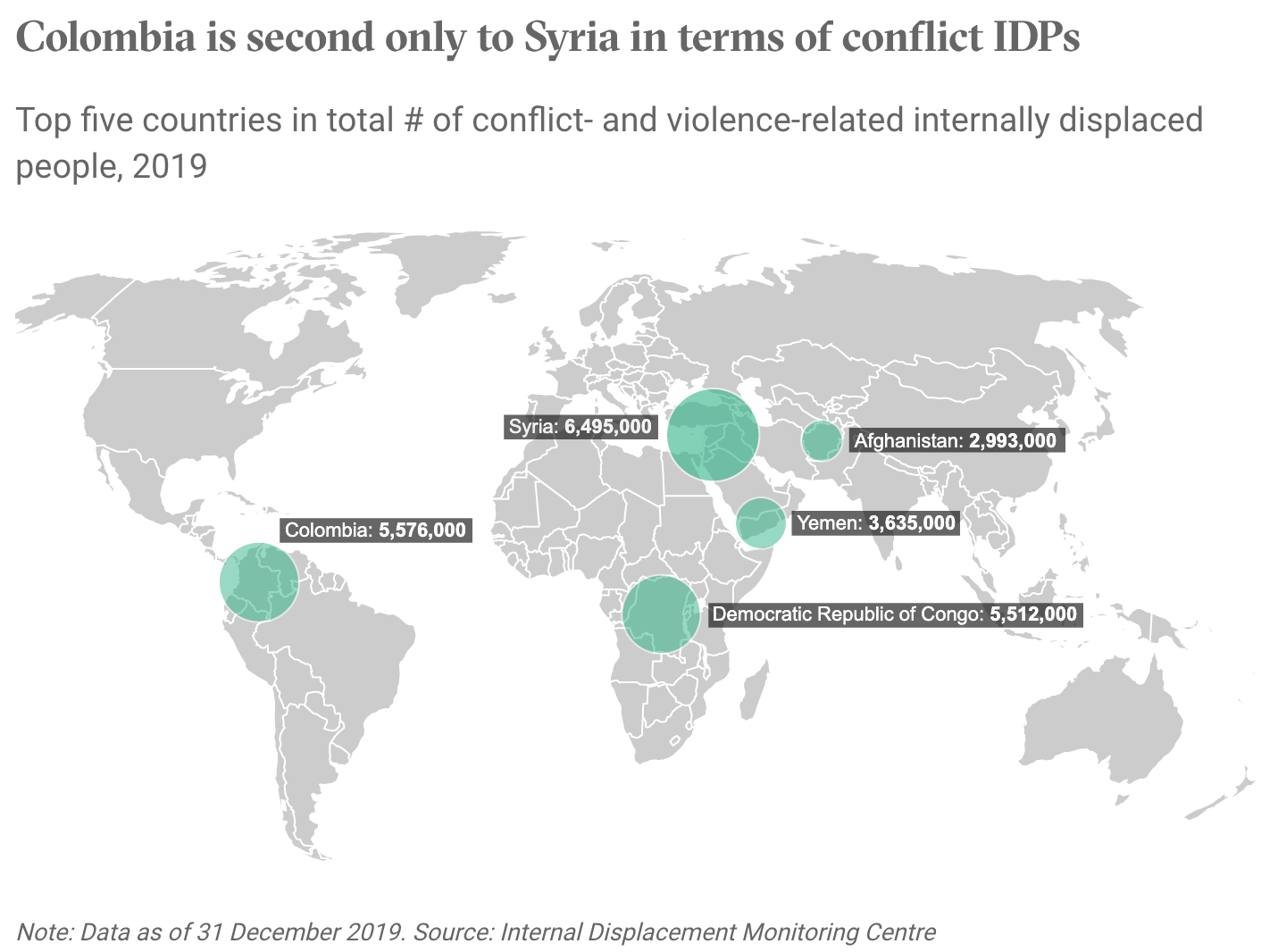

In fact, besides being the deadliest country on the planet for human rights and environmental defenders, at the end of 2019, there were 5,576,000 internally displaced Colombians, a figure second only to Syria.

Driving the anger of everyday Colombians are factors ranging from the fallout of a decades-long armed conflict, an impending economic crisis as a result of the pandemic, a peace process that appears to be falling apart at the seams, and far-right government that has failed to appease the growing frustration.

At the forefront the largest public demonstrations in decades, held at the end of 2019, these major issues have resurfaced stronger than ever during lockdowns imposed to hinder the spread of Covid-19. In 2021, it’s brought about a political awakening among Colombia’s youth, who refuse to be silenced a second longer.

Demanding a variety of government concessions, protestors are fighting for increased health and education funding, guaranteed income for those unemployed due to Coronavirus, and measures to put an end to gender-based violence.

Protest leaders, primarily Indigenous representatives, are also pushing for a meeting with President Duque to discuss the murders of activists, whose deaths have been wrongly attributed to leftist rebels and criminal gangs.

‘In 2017, there was a process of reactivation of youth in Colombia thanks in part to the expectation generated by the peace agreement,’ says activist Indira Parra of Cuidad en Movimiento, an organisation that seeks to build upon widespread struggle for a clean environment, affordable housing, and dignified urban living in Bogotá. ‘Parallel to this mobilisation of youth and new leaderships emerging in many areas, there’s been a systematic killing of social leaders that became active in the wake of the peace agreement.’

Parra speaks of the assassination of 309 social leaders and 90 politically violent massacres that occurred in 2020 alone – government responsibility for which, regardless of international criticism, was rejected by President Duque and his supporters.