A recent report suggests we’re facing ‘the greatest threat to mental health since the second world war,’ and a potential ‘tsunami’ of psychological problems, with Gen Z among the worst affected.

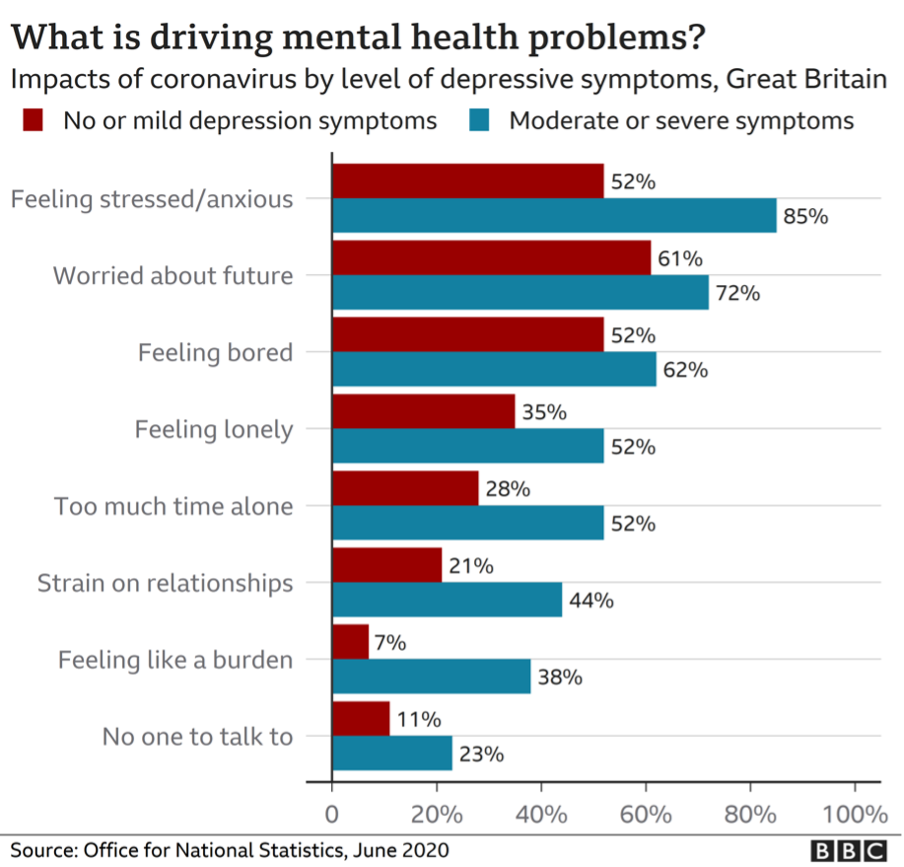

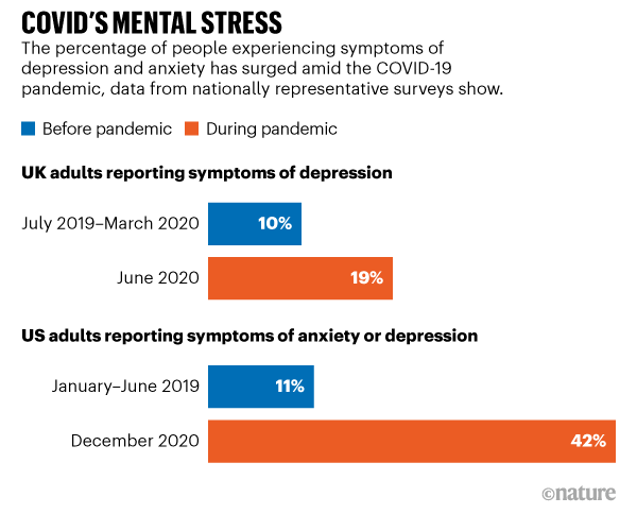

It’s no secret that the impact of the pandemic – global devastation, millions of deaths, economic strife, and unprecedented curbs on social interaction – has already had a significant effect on people’s mental health.

Of those currently experiencing anxiety and depression related to Covid-19, over half of them are Gen Z, most likely because young people are especially vulnerable to psychological distress and often have an intense need to socialise during adolescence.

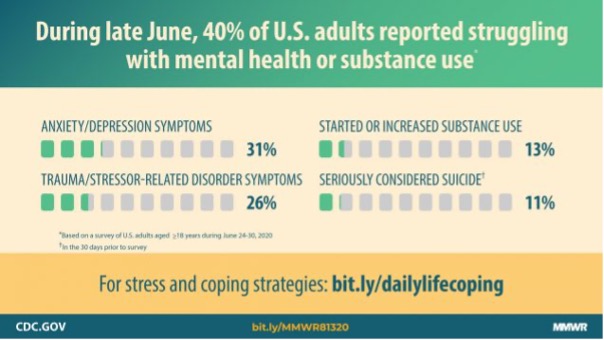

According to a study conducted by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 63% of 18 to 24-year-olds in the US are suffering as a direct result of the Coronavirus crisis, with a quarter of young adults resorting to increased substance use to cope, and the same number (25%) stating they’d considered suicide during the past month.

Dr Sarah Lipson, Assistant Professor at the School of Public Health in Boston, correctly attributes this to a ‘perfect storm’ of job losses, income uncertainty, isolation, absence of education, and the general atmosphere of unease and loss, with students of colour taking the biggest hit.

‘For the people between the ages of 21 and 25, this is a time of expansion in their life, with new connections and new things,’ she says. ‘That is all being halted. I think this is a hard time for parts of life to stand still when there is normally just this fast-paced developmental time where so much is happening socially and professionally.’

These harrowing statistics have raised alarm bells for experts, who are arguing that amid ‘the greatest threat to mental health since the second world war,’ the potential ‘tsunami’ of psychological problems we risk facing is in need of a great deal more attention, that it should be treated as seriously as containing the outbreak.

But how did the situation get so out of control?

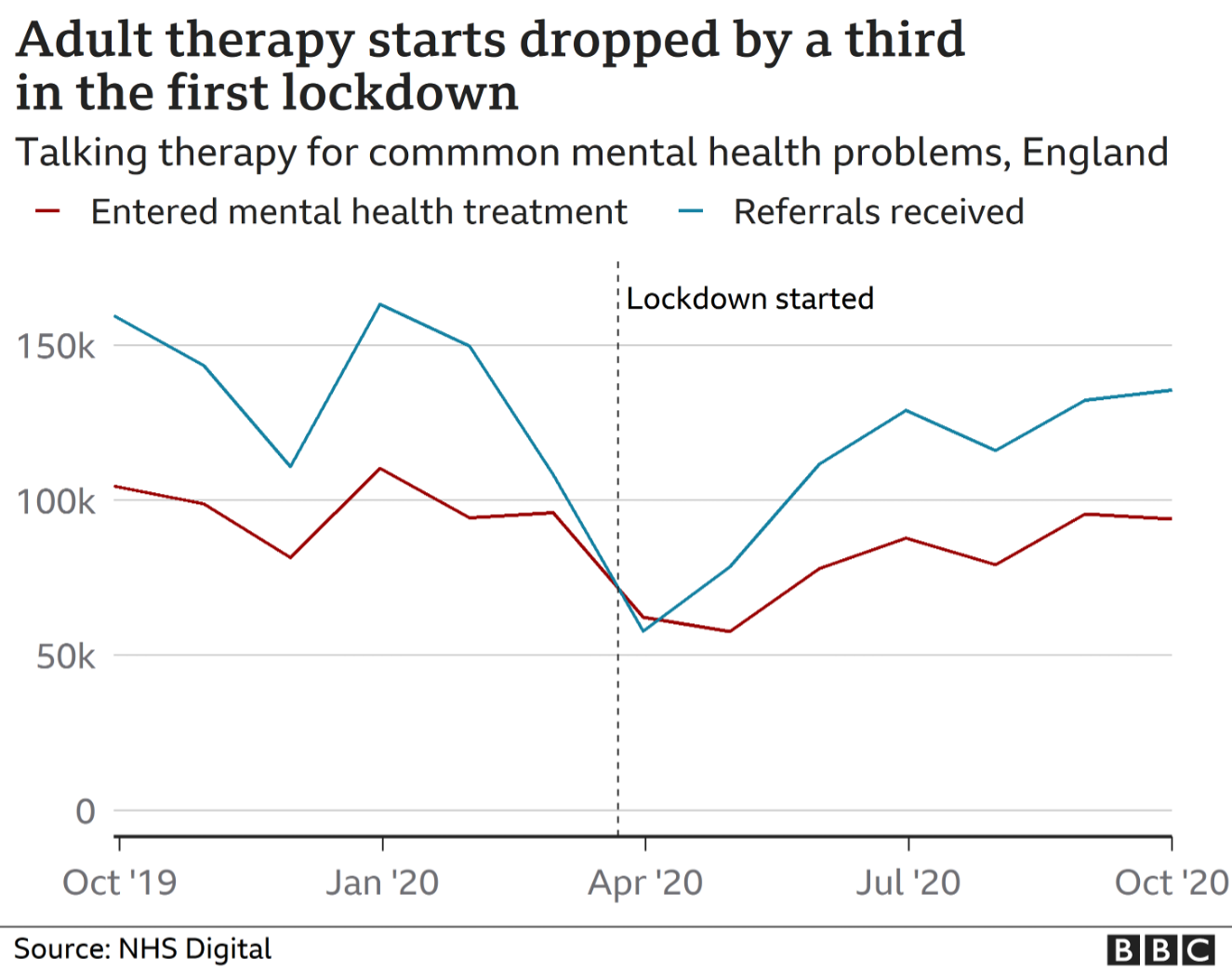

For one, very understandable, reason: fear of hospitals. In a survey, psychiatrists found that, while there’s been an obvious rise (43%) in emergency cases since last March (and despite mental health services remaining open), there’s been a noticeable drop (45%) in routine appointments.