Scientists are alarmed by a ‘dangerously fast’ growth in atmospheric methane. Reportedly now thrice as prominent in our atmosphere as pre-industrial levels, there are concerns that the planet may actually be harming itself.

Climate mitigation plans for methane are reportedly three times too low to meet goals outlined in the Paris Agreement. Oh good.

With the need to decarbonise industries taking precedence, it appears we’ve been overlooking the steady growth of methane – a gas, which worryingly, is 25 times as effective in trapping heat.

Slowing around the turn of the millennium, methane levels began a rapid and unexplained uptick in 2007. Levels have since risen gradually year on year, and researchers are concerned climate change may be creating a sort of feedback loop that is causing even more natural methane to be released.

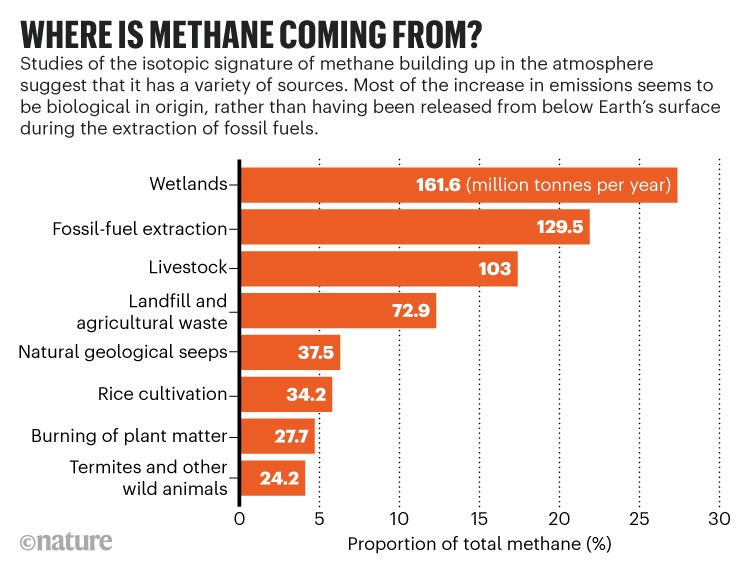

Essentially, climate scientists are pointing to our warming atmosphere as the reason for new wetlands sprouting across the globe.

With permafrost melting and water levels rising, these bogs, swamps, and marshlands – all of which are breeding grounds for bacteria that produce methane – are now largely considered the biggest offenders for warming tied to the gas, period.

‘Is [global] warming feeding the [methane] warming?’ asks Euan Nisbet, Earth scientist at the Royal Holloway University. ‘As yet, no answer, but it very much looks that way,’ he says.

This theory had been gathering momentum for years, but only now it is deemed a realistic assertion thanks to burgeoning satellite technology, and comparisons to methane far preceding the Industrial Revolution.