Young women (and men) from across the globe are tackling a worldwide issue of accessibility, attempting to level the playing field of public health.

Periods are not a privilege. It seems like a simple statement, akin to other truisms like ‘red and blue make purple’ and ‘thou shalt not kill’. However, it’s a notion that’s unfortunately proved hard to inscribe into political discourse. This is due in part to malice, in part to ignorance, and holistically to an outdated squeamishness about acknowledging women’s health issues.

The average woman menstruates for 2,535 days of her life. That’s seven years total of pads, tampons, ruined underwear, cramps, and red rivets of womb lining. Do you know what else you can accomplish in seven years? You could complete an undergraduate degree and a PhD, learn several languages fluently, travel to each country in the world multiple times, or grow a pretty decent sized tree.

For some, spending all this time dealing with the adverse effects of periods is inconvenient and frustrating. You could probably do all the activities listed above whilst bleeding from your vagina, but it would likely be far more unpleasant.

For others, experiencing a period can be prohibitive and devastating.

According to this 2017 study by women’s rights group Plan International UK, one in 10 British girls have been unable to afford sanitary products at some point in their lives, and 12% have had to improvise protection from household objects such as socks and cardboard. Over 130,000 young girls reported missing days of school due to a lack of resources for their period.

In the US, stats are similar. One quarter of women report having struggled to afford period products due to a lack of income. 46% of low-income women report having to choose between a meal and period products.

The notion that economies of scale are run on choice for the consumer is a myth. The way an individual chooses to divide their income should theoretically be up to them. In fact, that is not the case for ~50% of the world’s population. Women are necessitated by their bodies to buy products to manage their period in order to continue receiving the education and quality of life they’re entitled to.

Given that period products aren’t a luxury but a necessity, you’d think they’d also be a human right, and therefore free. This again is far from the truth.

Tampons, pads, and other women’s health products are currently taxed in most nations as ‘luxury’ items. The tax on menstruation was introduced at 10% VAT in the UK in 1973 when it joined the EU. It peaked at 17.5% in 1991, and settled on a reduced rate of 5% in 2001 after MP Dawn Primarolo introduced a bill to parliament.

In the US, feminine hygiene products are taxed at the exact rate of other ‘non-essential’ goods – some 10%, depending on state. For comparison, in the realm of men’s health, Viagra does not incur a tax.

For many years, feminist activists from across the gender spectrum argued that it is wrong for the state to charge women for having menstruating bodies. Yet there has been a persistent lethargy from governments who have neglected to take significant action on period poverty, and this is now being inherited by younger generations.

Previously, the fight against period poverty has struggled in the shadows of the public health sector, relying on a handful of courageous advocates to try and push it up the political agenda. It’s had to contend with the consistent relegation of periods to a ‘fringe issue’ despite the fact that periods are consistently relevant to half of parliament’s constituents – specifically to half the population, one quarter of the time.

A historical reluctance to acknowledge these excesses of the ‘transgressive’ female body, which presumably dates back to a time when people thought menstruation had a werewolf-like connection to lunar cycles, seemed to persist in the halls of a parliament predominantly sat by men over 50. The journey from lack of understanding to lack of discourse to lack of legislation is an easy one to follow.

Today, there’s a new generation of young human rights advocates who are thrusting the issue of period poverty into the limelight. Or, more accurately, dragging crusty politicians to confront a human rights issue and the prevailing feeling of shame that their perpetuation of archaic taboos and gender difference has caused.

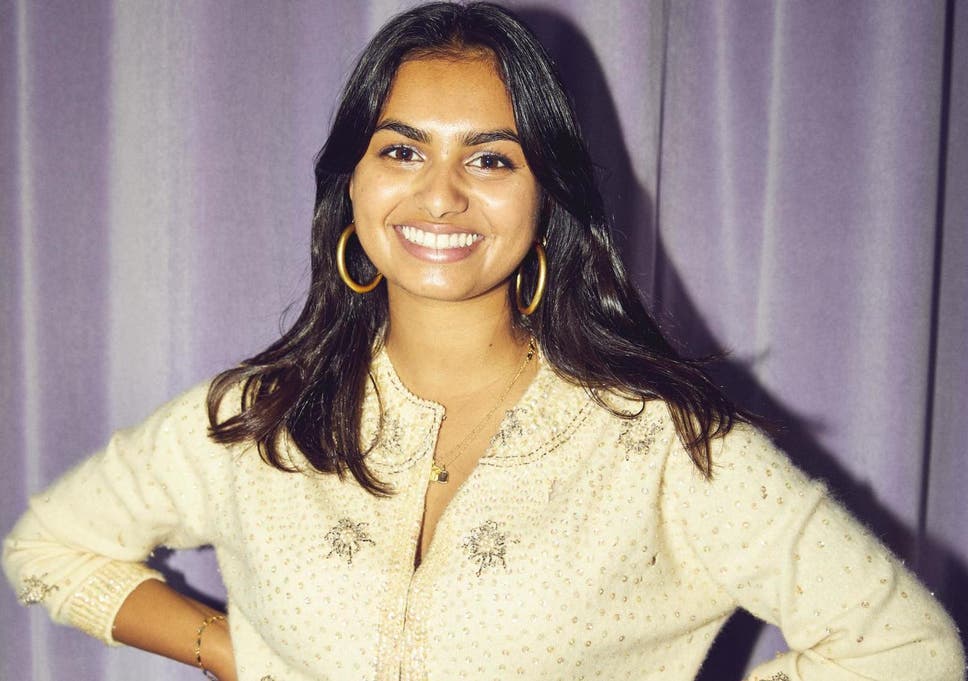

Amika George

Amika George is a 19-year-old Londoner who started campaigning on period poverty in 2017. She was inspired to begin work on the issue in response to the Plan International Study which was conducted that year.

That same year she began the #freeperiods movement – a national campaign calling for the government to fund free sanitary products for schoolchildren in receipt of free school meals. ‘As these are the children from the lowest socio-economic backgrounds, they are most likely to be faced with this monthly burden’ she said in an article she wrote for the Guardian.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61825289/2018_Period_Campaign_259_Edit.0.jpg)