One of the most successful marketing ploys of the 20th century was when BP framed you for climate change.

It’s a well-known fact that the most effective defence in a criminal trial is an alternative suspect. British Petroleum, the second largest private oil company in the world, was certainly aware of this fact in 2000 when it rebranded itself ‘Beyond Petroleum’, beginning an international marketing and PR campaign which would popularise the now very familiar ‘carbon footprint’.

BP’s second christening came a little over ten years on from James E. Hansen’s ground-breaking Senate testimony that ‘the greenhouse effect has been detected and is changing our climate now’. At this time, even the sceptics were beginning to look at the severe drought and heat ravaging the US yearly and the vast fires in the Amazon with raised eyebrows. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had steadily been accumulating reports that pointed the finger firmly at the oil and gas industries, and as the hole in the ozone layer continued to grow there was chatter, even then, of a carbon tax.

Heavy emitters went into damage control mode, knowing it was imperative they craft their own climate change narrative alongside the one writ large by science. So, throughout the early aughts, you began to get ads like this one:

Geometric patterns in bright colours oscillate into satisfying formations as a soothing British woman waxes lyrical about solar panels and ‘cleaner petrol’. ‘Can 100,000 people in 100 countries come together to build a new brand of progress for the world? We think so’, she declares triumphantly as the violins reach their crescendo.

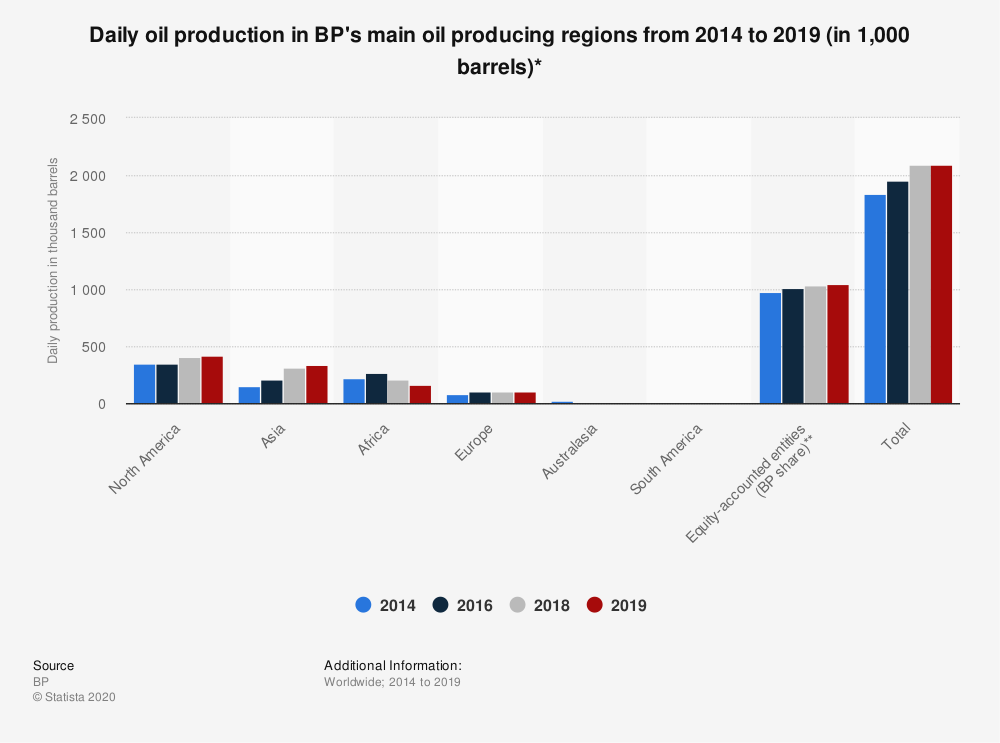

At the time of this campaign’s release, BP was producing around 2 million barrels of oil per day and had just bought their 13,000th gas station. 100,000 people in 100 countries couldn’t put a dent in the impact this one petroleum company could have if it divested even a fraction of its funds into green energy.

It was clear the message that the oil and gas industry was sending: heat-trapping carbon pollution is your problem, not the problem of the companies drilling deep into the Earth for, and then selling, carbonaceous fuels refined from ancient, decomposed creatures.

Like many fossil fuel giants, BP had hired a PR team, employing the services of the firm Ogilvy & Mather, to help turn the climate tables on the individual. The next trick in their playbook was to unveil BP’s ‘carbon footprint calculator’.

‘It’s time to go on a low-carbon diet’, this archived webpage from 2004 declares, navigating the unwitting visitor to input details of their shopping, food, and travel habits before a program spat out their aggregated ‘impact’ on the planet. In 2004 alone, nearly 300,000 people worldwide calculated their carbon footprint on BP’s website. The innovation was matched by yet another manipulative ad campaign by Ogilvy & Mather whereby the firm wandered London suburbs and interrogated average people about their carbon footprint.

Slowly but surely, BP was linguistically replacing itself in the carbon conversation with the personal pronouns, ‘I’, ‘we’, and ‘you’. Fast forward, and it’s evident that BP itself has done nothing to curb its own footprint: the company is still producing an average of 3.8 million barrels of oil and gas every day, and in 2019, it purchased a new oil and gas reserve in West Texas that it lauded to shareholders as its ‘biggest acquisition in 20 years’.

All the while, the concept of a personal ‘carbon footprint’ has become more and more intertwined with how we conceptualise climate change. Over a decade later and carbon footprint calculators are everywhere – strewn across travel sites, collated into helpful guides by influential publications like The New York Times, and across environmental protection agency websites. The term carbon footprint has been infused into our normal, everyday lexicon.

The true nature, and true genius, of the scam becomes clear when you get into the nitty gritty of an individual’s carbon options in a world still run predominantly on gas and oil. A few years after BP began their ‘carbon diet’ campaign, researchers at MIT calculated the carbon emissions of a homeless man who ate in soup kitchens and slept in homeless shelters in the US. They found that that individual would still be indirectly emitting some 8.5 tonnes of CO2 each year.

BP sought to explain the carbon crisis in a way that assigns responsibility for it to the careless individual driving a diesel car, whilst BP itself registers its own concerns by appearing already to be doing something about it, all the while avoiding outlining a specific accountability plan. But, if even a homeless person has an unsustainability high carbon footprint, the reality for the average individual is even more untenable as long as fossil fuels are the basis for the energy system.