The ongoing Barry Arm landslide has alerted experts, driving a push to understand and monitor its progress before it triggers a megatsunami that could devastate all surrounding life.

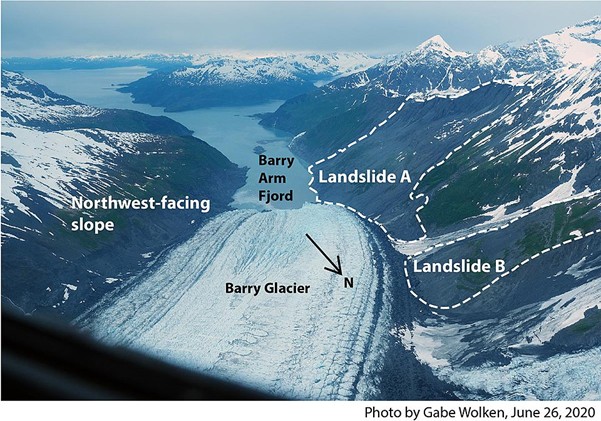

In 2019, Valisa Higman was boating around the Barry Arm fjord when she noticed massive and unusual fractures on the cliffs above the nearby Barry Glacier in Alaska. This kickstarted major efforts, with satellite data confirming that a massive section of the mountain had descended about 180 meters between 2009 and 2015.

Just a year after the discovery, a group of scientists came together to release a letter to the state of Alaska, warning its inhabitants about the slope’s instability, and worse, that it could trigger a catastrophic tsunami.

By comparing historical records of the mountain, it was revealed that the landslide had already started its descent in the late 1950s. Aerial images from this period show the scarf of the cliff detached from the bedrock, indicating that the mountain was slipping under its own weight.

However, only between 2010 and 2017 did the landslide accelerate downwards, shifting it to a highly hazardous natural event. Experts cited the cause as the loss of the mountain’s underlying support and of course, climate change.

The scary reality of this event is that should 500 million cubic meters of rock from the landslide fail altogether at once, it would lead to a megatsunami, which is vastly different from the waves caused by usual undersea earthquakes.

When the rocks hit the water, and estimated initial wave that’s 200 meters high would hit ground zero, which is within the Barry Arm fjord itself. Then, a secondary wave would surge up the mountain walls around it, potentially reaching heights of 500 meters devastating all flora and fauna. With the area having high community presence from the nearby town of Whittier, kayakers, fishermen, and cruises alike, many people could be caught in the damage.

Within the proximity of this megatsunami is also Prince William Sound, which was the location of the cataclysmic Exxon Mobil oil spill that occurred 36 years ago. The accident saw the spillage of up to 11 million gallons of crude oil killing thousands of seabirds, sea otters, and orcas, among countless other species. While cleanups took place, scientists estimate that as much as 23,000 gallons of oil remain immobilized, buried and bound to sediment.

With a potential megatsunami in the offing, it would scour the shorelines, remobilizing these oil-bound sediments back into the ocean. While the original spill stayed mostly on the surface, this remobilized oil would likely mix into the water, making it harder to clean, while poisoning wildlife once again.