In this astonishing report of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the Congo Basin, often known as the ‘Lungs of Africa’, yet again is hailed for its ecological importance.

In the last decade, scientists have revealed over 700 more species of animals and plants that were previously unknown to the rest of humanity, in this rainforest of the African continent.

This can be seen as proof of the extraordinary biodiversity of the region. This knowledge, in turn, brings to attention the critical sustainability of some of world’s most vital environments while raising the concern of their unsustainable destruction.

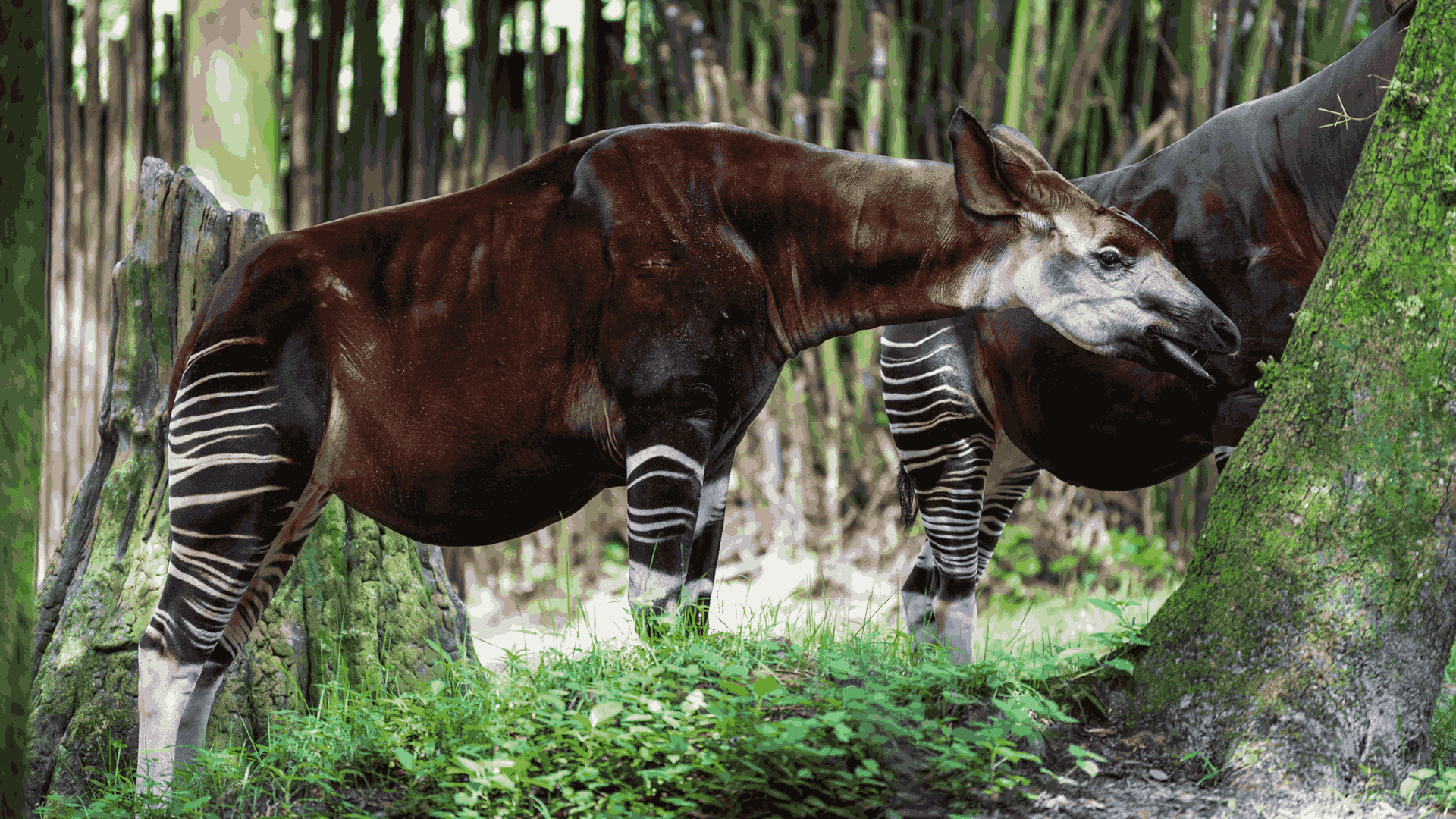

The new discoveries include a variety of species, from colorful frogs to plants and mammals entirely off record. Every species is part of the network of life that this rainforest is responsible for, helping it to be one of the world’s biodiversity heritage sites.

This forest, spanning six countries, is next in size to the Amazon and also serves as the second largest natural carbon sink. This sequesters a staggering volume of carbon emissions.

The WWF researchers say the dawn of these discoveries has just begun, for the forest’s complex and dense terrains makes large-scale explorations particularly difficult. The new species are not only a source of biodiversity data but also a living testimony of how diverse the Congo Basin is in flora and fauna, stated as one of the richest ‘biodiversity hotspots’.

The discovery highlights the innate worth of the Congo Basin as a reservoir of life. Safeguarding the basin means the safety of both old and new species, a great number of which are yet to be thoroughly studied for their putative roles in medicine, agriculture, and ecosystems.

Furthermore, the Congo Basin is the subsistence ground for over 75 million people who depend on it for food, water, and medicine (countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea). Its conservation is not just of ecological importance but also social and economic.

Nonetheless, the Congo Basin is still suffering from the continuous threat of deforestation and both mining and agricultural expansion. Approximately 1.5 million hectares of its forest perish annually, which is the result of illegal logging, unsustainable farming methods, and infrastructure development.

Such a catastrophe is terrible for both native and novel species. The shrinkage of habitats splits populations apart, which in turn, forces many species to the brink of extinction. The decreased forest cover also interrupts the delicate ecological balance and produces cascading effects on the food chain.

The leakage in carbon dioxide resulting from deforestation also accelerates global warming in significant increments.

To protect the Congo Basin, ecological organizations, governments, and local community leaders need to join forces. This is achievable through legal frameworks that offer the protection of natural habitats, the promotion of sustainable land use schemes, and the eradication of illegal activities that damage the region’s ecology.

As with all mitigation and adaptation funding, it is crucial for funds from the developed world to be mobilized for practical safeguarding and hiring the essential expertise required to succeed.

While that fact is rightly perceived as negative, The WWF’s report at least heaps pressure on countries to rethink their common goal in preserving biodiversity.

After all, the Congo Basin’s damage not only represents an African issue, but a global one. Fail to take an active hand in its preservation and both climate regulation and delicate species are at risk.