Many developing countries are deep in financial debt. More often than not, however, they are rich in biodiversity. An increasingly popular climate agreement could enable them to minimise the debt they owe to wealthy nations – as long as the money saved is placed into environmental protection and adaptation projects.

Levels of debt in low-income and developing nations are steadily rising.

This is a result of regularly borrowing money from wealthy nations in order to keep their economies afloat, which skyrocketed throughout the pandemic and continues to increase in response to inflation.

By the end of 2020, the average debt level for developing nations stood at 42 percent of their gross national income. That’s 26 percent higher than it was only a decade before.

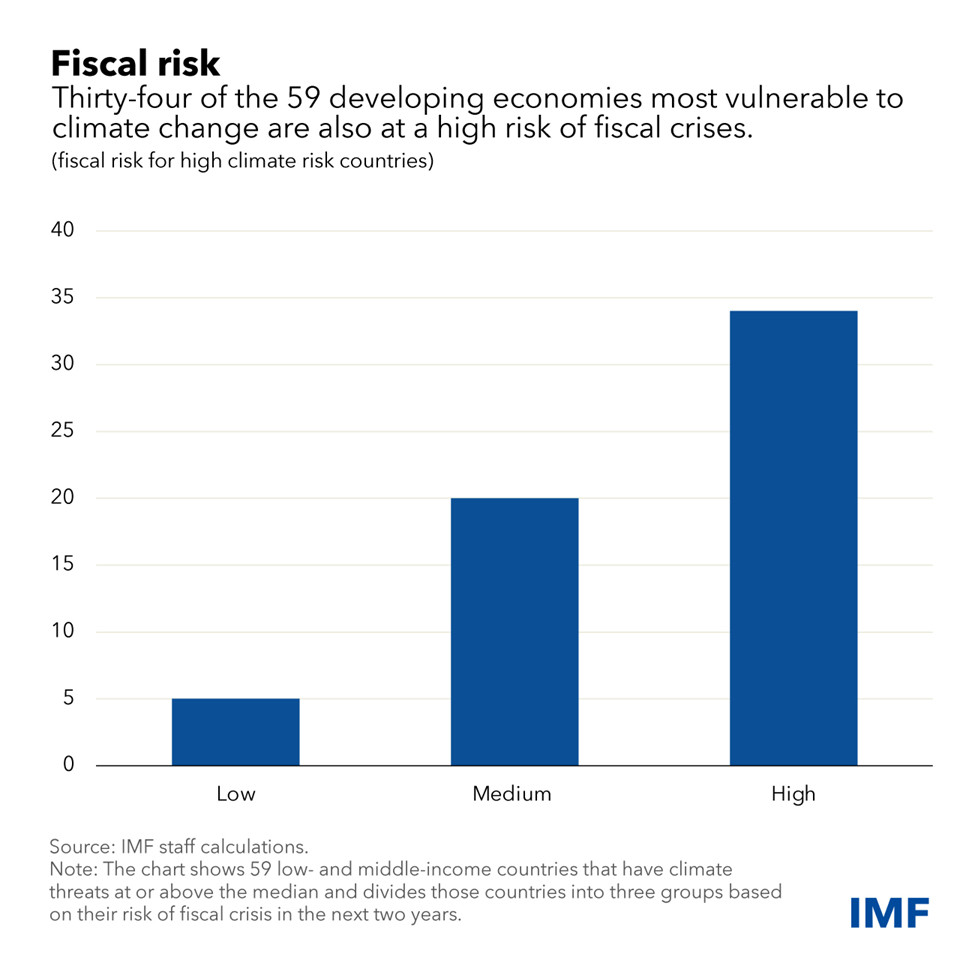

Many developing nations – excluding China and India – have low annual emission levels when compared to wealthy nations. They are also often rich in biodiversity, yet unfairly find themselves located in regions most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Making matters worse, after submitting national debt payments, most of these countries have little leftover funds to invest in environmental conservation, climate adaptation, and mitigation projects.

This creates a vicious cycle of inequality, climate injustice, and poverty.

As the world’s most powerful leaders look for innovative ways to improve economic equality and take climate action, many are considering a two-for-one deal. This entails allowing developing nations to swap their national debt payments for investments into local environmental protection projects.

The most recent deal of this kind has occurred between Portugal and Cape Verde.

Before we get into the details of Portugal and Cape Verde, it would be helpful to look at the three different kinds of ‘debt-for-climate’ agreements that can be made.