Researchers are looking to deploy 50,000 ocean sensors to track ships, storms, wildlife, and weather in 2020.

With Musk’s 60 Starlink satellites already filling the sky, oceanographers are now looking to build an interconnected network of sea sensors spanning an area larger than Texas.

As we sit here today it’s feasible to suggest that we probably know less about the high seas than we do the moon, but tech tycoon John Waterson (yup, seriously) is looking to change that in 2020.

Having already pioneered the ‘Internet of Things’, which refers to the interconnectivity of everyday appliances like say your watch, doorbell, voice activated speaker, and bath faucet, Waterson is now funnelling his creative energy and resources into the ‘Ocean of Things’. Could probably do with a new PR head, I know.

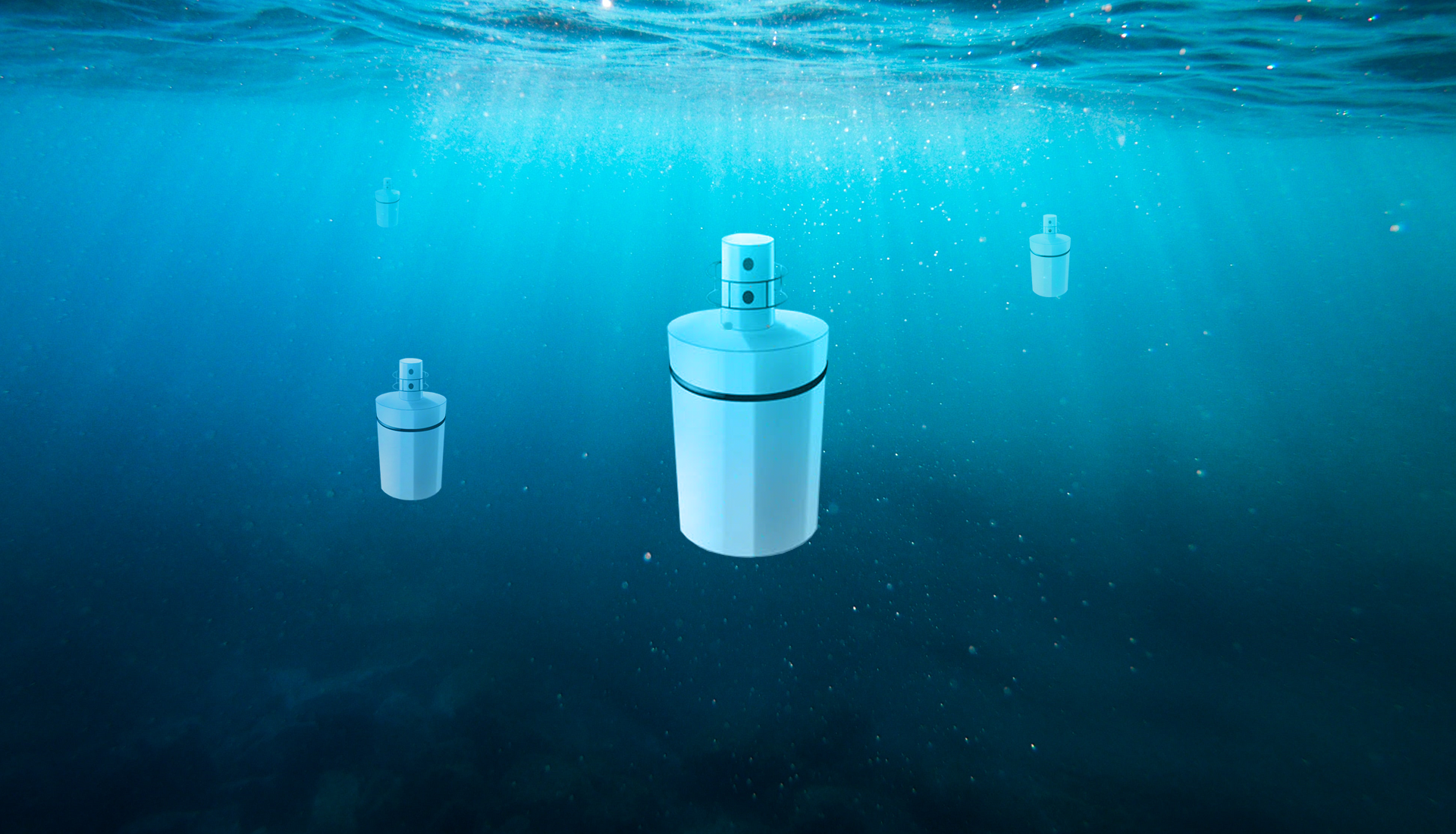

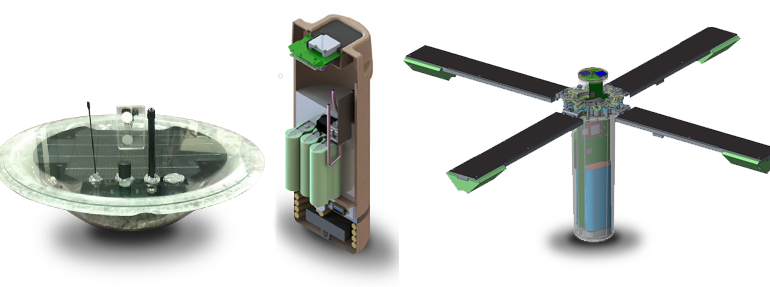

If all goes to plan Waterson will release a phalanx of 50,000 ocean sensors which will provide us with a wealth of knowledge we’ve never had on the deep blue. Teasing the wallets of oceanographers, meteorologists, and marine biologists with specialist info is high on the agenda too. Let’s not kid ourselves.

While the project’s main aim is to track ships and ‘anomalous maritime activity’ – to combat illegal fishing and piracy on a global scale – Waterson has loftier plans for the tech too. Each sensor will gather live data on water temperature, water quality, wave heights, weather conditions, and wildlife behaviours, and will feed findings back to government-owned cloud networks for analysis.

Just think about it for a second, how invaluable could this information be? We could pinpoint typhoons and tsunamis at their origin way ahead of time, we could more efficiently tackle commercial whaling by simultaneously monitoring the live paths of sea mammals and illegal vessels. We could spot icebergs and isolate oil spills early. Maybe, just maybe, we could even banish climate change deniers for good with real time data on rising sea temperatures. You can’t argue with facts! (anymore).