AI is reportedly capable of predicting where crimes will take place up to a week ahead of time. The tech’s accuracy is around 90%, but there are concerns about its potential to perpetuate biases.

It may sound like something straight from the Bat Cave, but this tech exists for real and may even be widely utilised in the near future.

Scientists have reportedly found a way of predicting when and where criminal activity will take place using sophisticated AI. No, we’re not describing the plot of Minority Report.

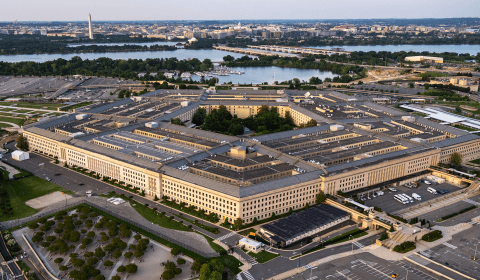

Researchers at the University of Chicago trialled the technology in eight major US cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, mapping out digital iterations of urban areas within a 1,000 square-foot radius.

Its machine learning systems were fed historical crime data recorded in the years between 2014 and 2016, impressively managing to pre-empt illegal activity 90% of the time. You can see the study for yourself in the science journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Sufficiently describing the tech, lead professor Ishanu Chattopadhyay stated: ‘We created a digital twin of urban environments. If you feed it data from what happened in the past, it will tell you what’s going to happen in future. It’s not magical, there are limitations, but we validated it and it works really well.’

Following these same principles, AI-based tech is widely in use now across Japan – though not to intercept criminals, but primarily to inform citizens of offender hotspots to avoid at particular times – and for the most part, it’s an effective system.

We have been warned previously, however, that use of AI in law enforcement has the potential to perpetuate harmful biases.