BED affects three times the number of people than anorexia and bulimia combined, but despite how common it is, research into and awareness of the condition remains limited.

In our image-obsessed world, the fact that so many people suffer from an eating disorder is plausible and saddening.

Every day, despite body positivity movements and calls for social media platforms to better regulate toxic trends, the amount of individuals struggling with a ‘morbid preoccupation with food’ increases.

Currently, the figure stands at nine per cent of the entire population.

Of course, since the height of heroin chic, we’ve become far more considerate towards those impacted and our understanding of how to support them has improved tenfold.

However, amid our determination to reject the fixation with skinny-worship that’s brought on waves of anorexia, bulimia, and other restrictive behaviours, there’s one condition in particular that seems to have slipped beneath the radar.

Binge Eating Disorder, or BED, is defined as someone having recurrent and persistent episodes that involve consuming large quantities over short periods of time.

It can take the form of eating much more rapidly than usual, eating until uncomfortably full, eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry, eating alone due to embarrassment, and/or feeling disgusted with yourself afterwards.

Yet although it’s incredibly common and affects three times the number of people than anorexia and bulimia combined (a study in 2017 found that BED made up 22% of eating disorder cases, with anorexia accounting for 8%, and bulimia 19%), research and awareness remains strikingly limited.

This is because bingeing is a fundamentally misinterpreted act.

Culturally, it’s viewed as an absence of willpower and, owing to prevailing weight stigma, is often inaccurately associated with people who are obese.

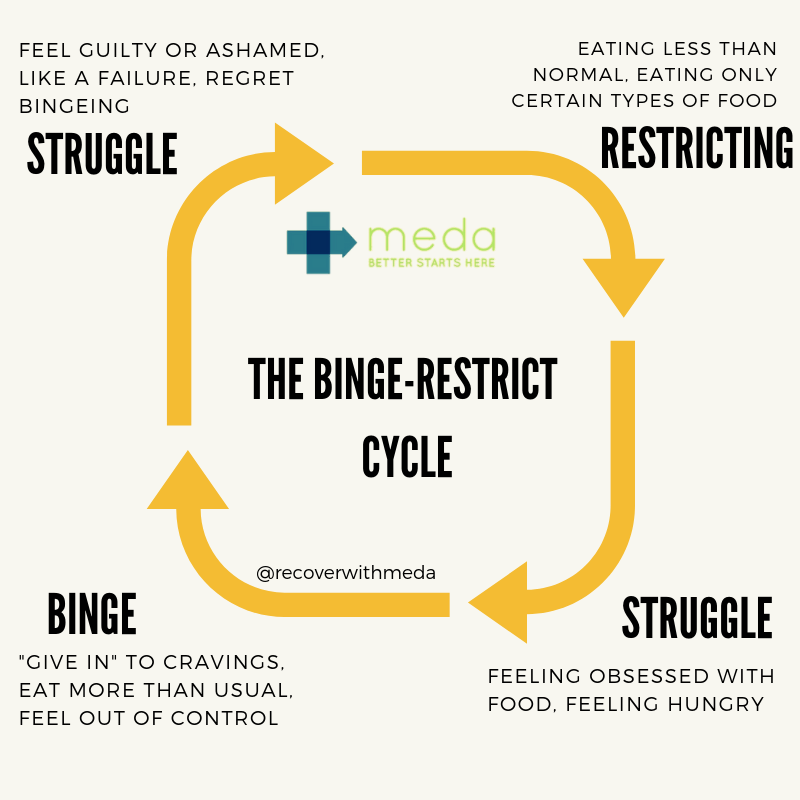

But as Beat clarifies on its website: ‘BED is not about choosing to eat large portions, nor are people who suffer from it just “overindulging” – far from being enjoyable, binges are very distressing, often involving a much larger amount of food than someone would want to eat.’

‘People may find it difficult to stop during a binge even if they want to. Some people with binge eating disorder have described feeling disconnected from what they’re doing during a binge, or even struggling to remember what they’ve eaten afterwards.’

At its core, BED is marked by the emotional distress and sense of a lack of control that drives it, by the guilt surrounding bingeing, and by the absence of compensatory habits like purging so that episodes happen in cycles and can last for weeks on end.

Using food as a weapon to combat intense feelings they’re unable to tolerate, people with BED are trapped in a pattern of self-loathing, which our failure to recognise the eating disorder as being on par with those we already take seriously is doing nothing to avail.