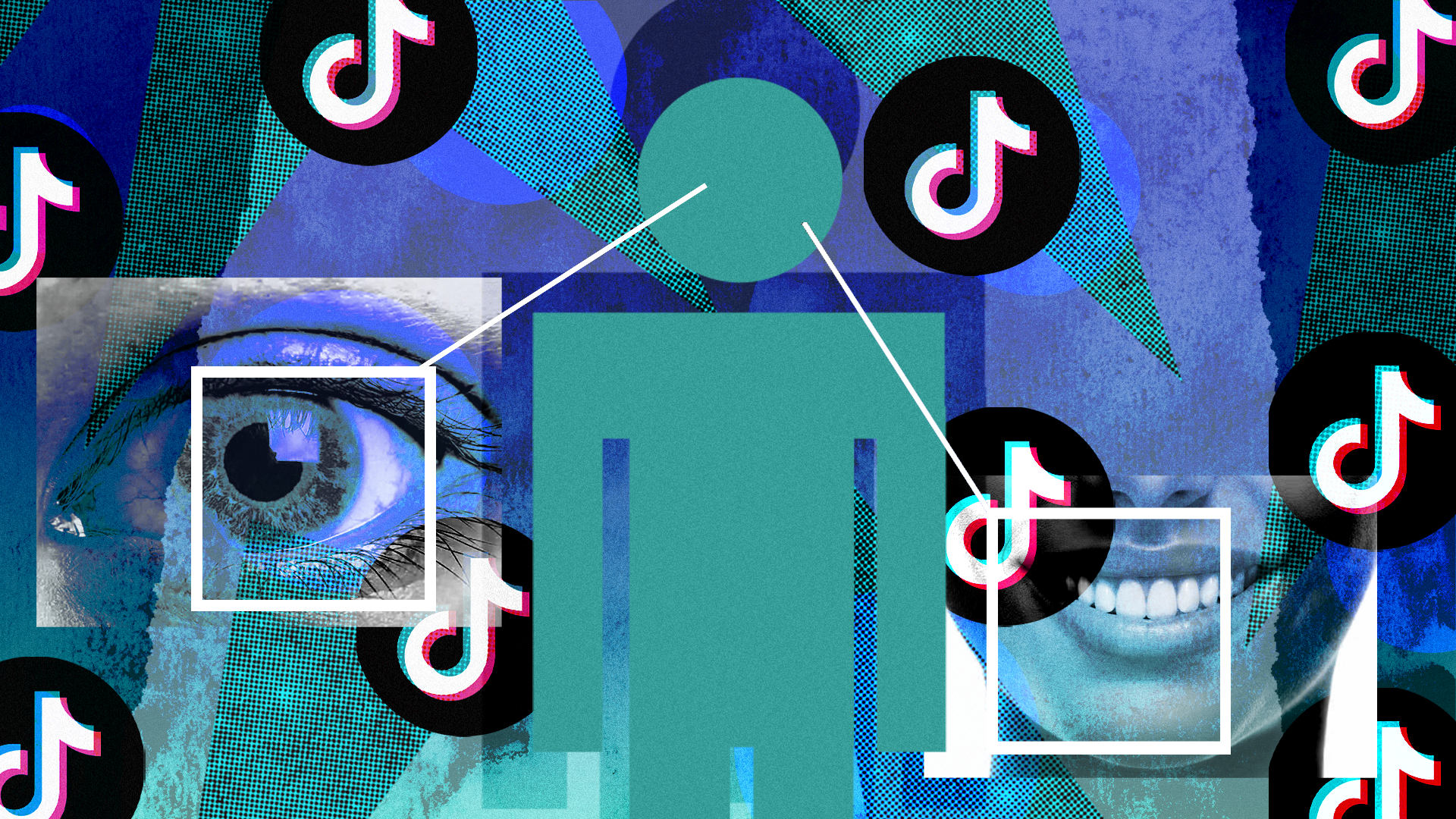

Social media is adept at consistently making us question whether or not our appearance meets an extremely high standard, all while continuing to shove algorithmic ‘sameness’ down our throats. Isn’t it time we stopped letting the Internet dictate the way we perceive our facial anatomy?

Ever since TikTok took over during the pandemic, it’s bolstered the influence of already-problematic beauty standards, bringing a slew of hugely unattainable ideals with it.

Whether it be the shameless lack of transparency surrounding cosmetic procedures, the toxic anti-ageing rhetoric, or creators using filters that have evolved to be so convincing we find ourselves wondering what anyone actually looks like anymore, this kind of content has transformed social media into a catalyst for deep insecurity.

While I’m pretty good at recognising my own triggers and putting down my phone when doubt starts to creep in, impressionable young people (who spend an average of two hours on TikTok a day) may not be as well-equipped.

The stats speak for themselves.

From April to October 2021, the NHS saw UK hospital admissions for anorexia, bulimia, and other eating disorders in teenagers rise by 41 per cent, a spike that experts claim is linked to the pandemic pushing most of our lives online.

According to Dove, 50 per cent of girls believe ‘they don’t look good enough without photo editing’ and 60 per cent ‘feel upset when their real appearance doesn’t match the digital version.’

@maggiemaebereading i find the perception of these things so fascinating ib: @bug_lov3r #deerpretty #catpretty #bunnypretty #foxpretty #lalala #okokok #didyouseetheway ♬ Did you see the way he looked at me – Hannah

More recently, a study from the American Psychological Association (APA) found that limiting screen-time is a sure-fire means of preventing ourselves from developing the poor body image and damaging behaviours that go hand-in-hand with extensive social media use (which, of course, is no surprise).

‘Youth are spending on average, between six to eight hours per day on screens, much of it on social media,’ says the report’s lead author, Dr Gary Goldfield of the CHEO Research Institute.

‘Social media exposes users to hundreds or even thousands of photos every day, including those of celebrities and fashion or fitness models, which leads to an internalisation of beauty ideals that are unattainable for almost everyone, resulting in greater dissatisfaction with body weight and shape.’

But I’m not here to talk at length about something we’ve been acutely aware of for years. Instead, I’d like to focus on the ‘survival of the prettiest’ culture that TikTok is currently fostering despite this awareness.

‘Are you cat pretty (sharp, defined features), bunny pretty (soft, round features), deer pretty (delicate, graceful features), or fox pretty (elongated, seductive features)?’, a robotic voice asks me, as part of the latest trend to go viral on the app, through the speaker of my phone.