The UK’s Advertising Standards Authority has ruled that social media influencers must now disclose when they use ‘misleading’ beauty filters on sponsored posts.

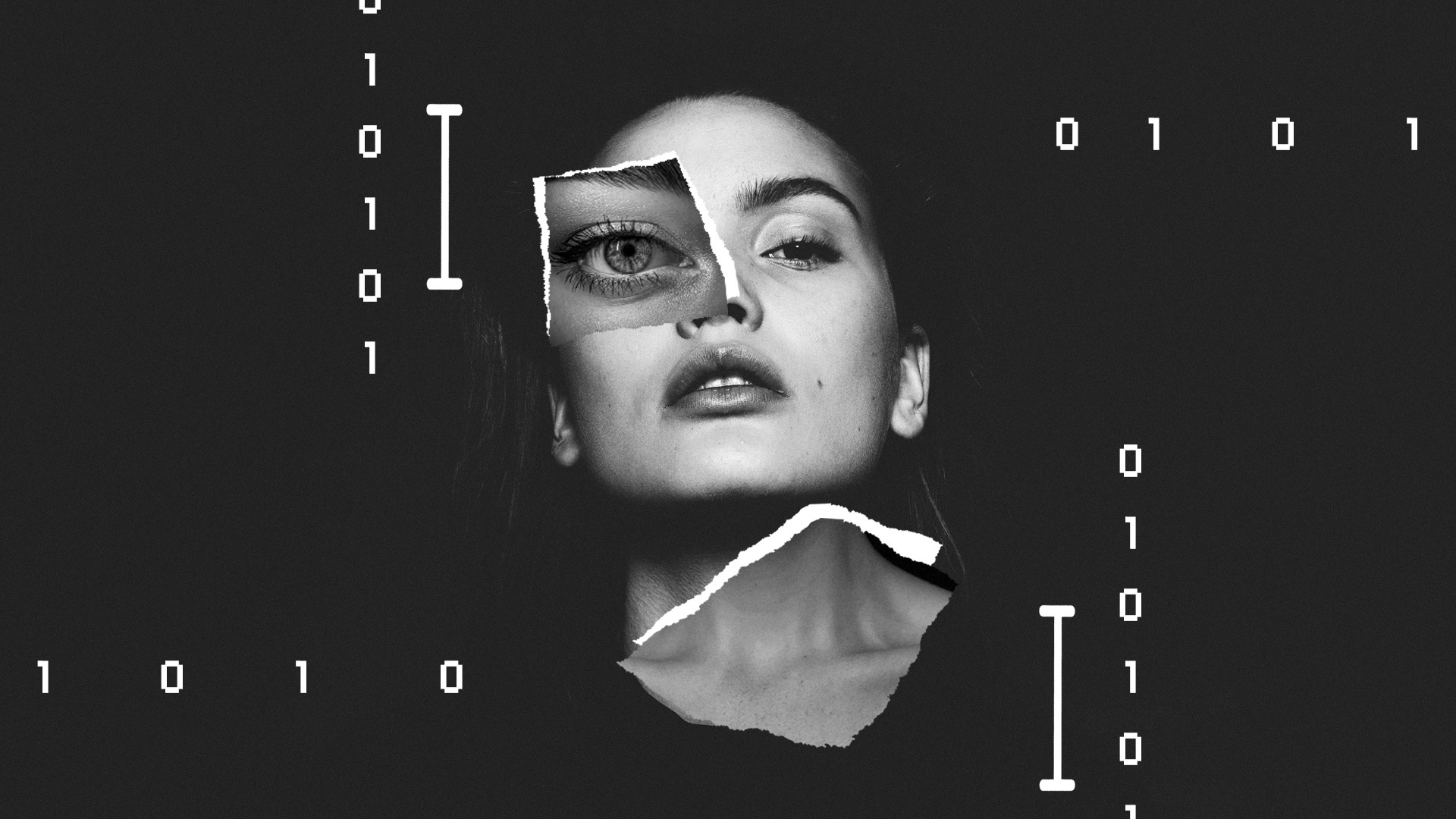

Ever since ‘fake aesthetic’ filters began flooding our Instagram feeds in early 2019 they’ve become common place, so much so that you may not even realise you’re looking at an altered selfie that can manipulate anything from eye colour to your jawbone.

Whether this involves skin that appears slightly too flawless or overly chiselled and exaggerated features, for years these methods of retouching have encouraged us to conform to problematic online standards, causing a wave of ‘Insta-dysmorphia.’

Though many of us may occasionally delight in seeing what we look like with smaller noses, reconstructed jaws, and a larger pout, it wasn’t until Instagram enforced a ban on such effects that the world came to realise quite how damaging they’d become.

In a recent study, it was unveiled that around half of the female participants (aged between 11 and 21) use apps or filters regularly, to make photos of themselves ‘look better’ before publishing them.

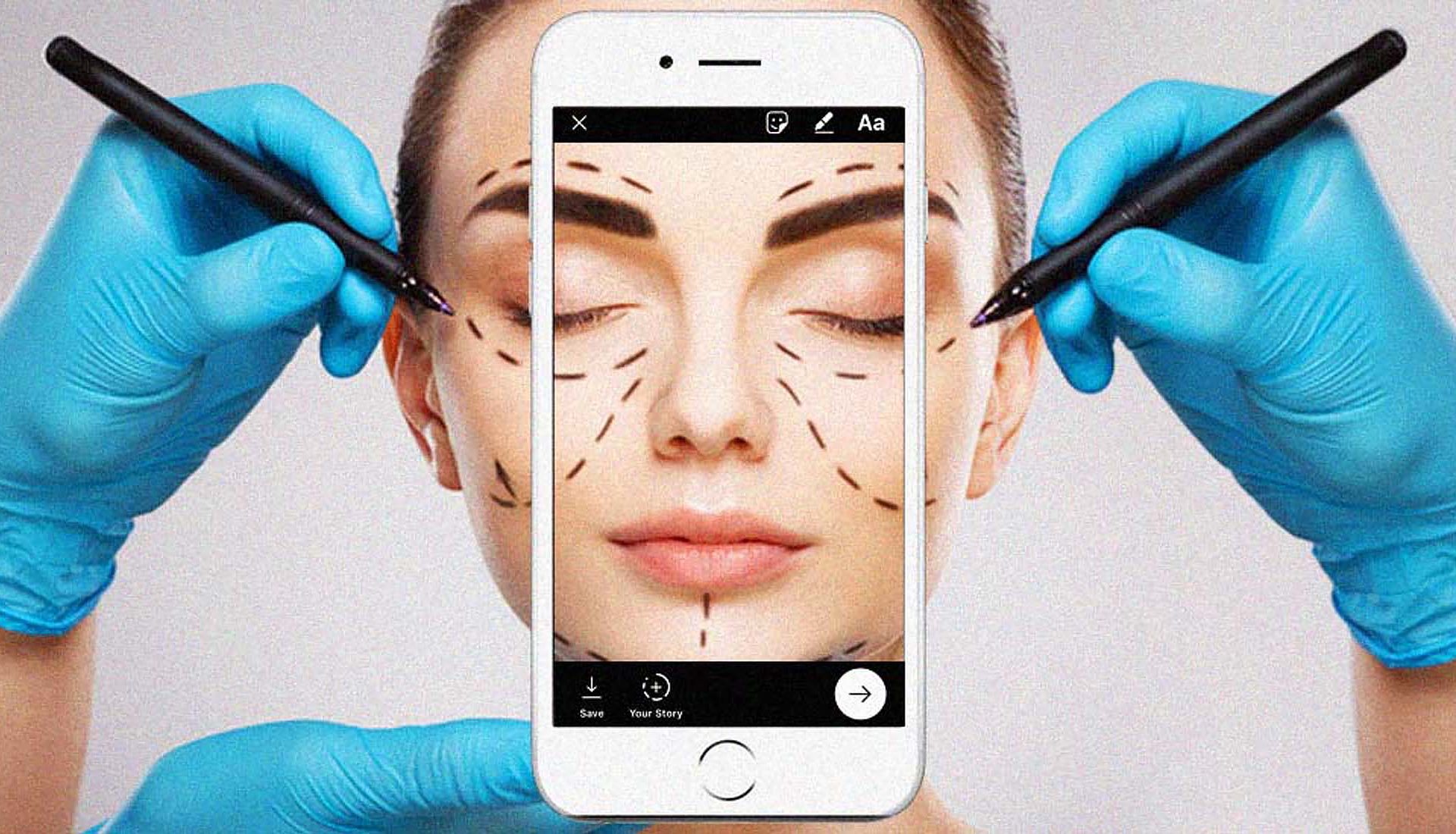

Now, taking things a step further to protect the self-esteem of impressionable young people, the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) has ruled that social media influencers must disclose when they use a beauty filter to promote products.

Responding to the #filterdrop campaign founded last July by Sasha Pallari in the hope we’d start seeing more ‘realness’ online, the new law will prohibit the use of filters if they amplify the results cosmetics or skincare being sold by brands are capable of achieving.

This essentially means that influencers and celebrities being paid to advertise will not be able to upload content that’s been modified to change the shade or texture of what they’re endorsing.

Anything that goes against these regulations will be taken down, and the companies behind the harmful posts will be forbidden from appearing on the site again.