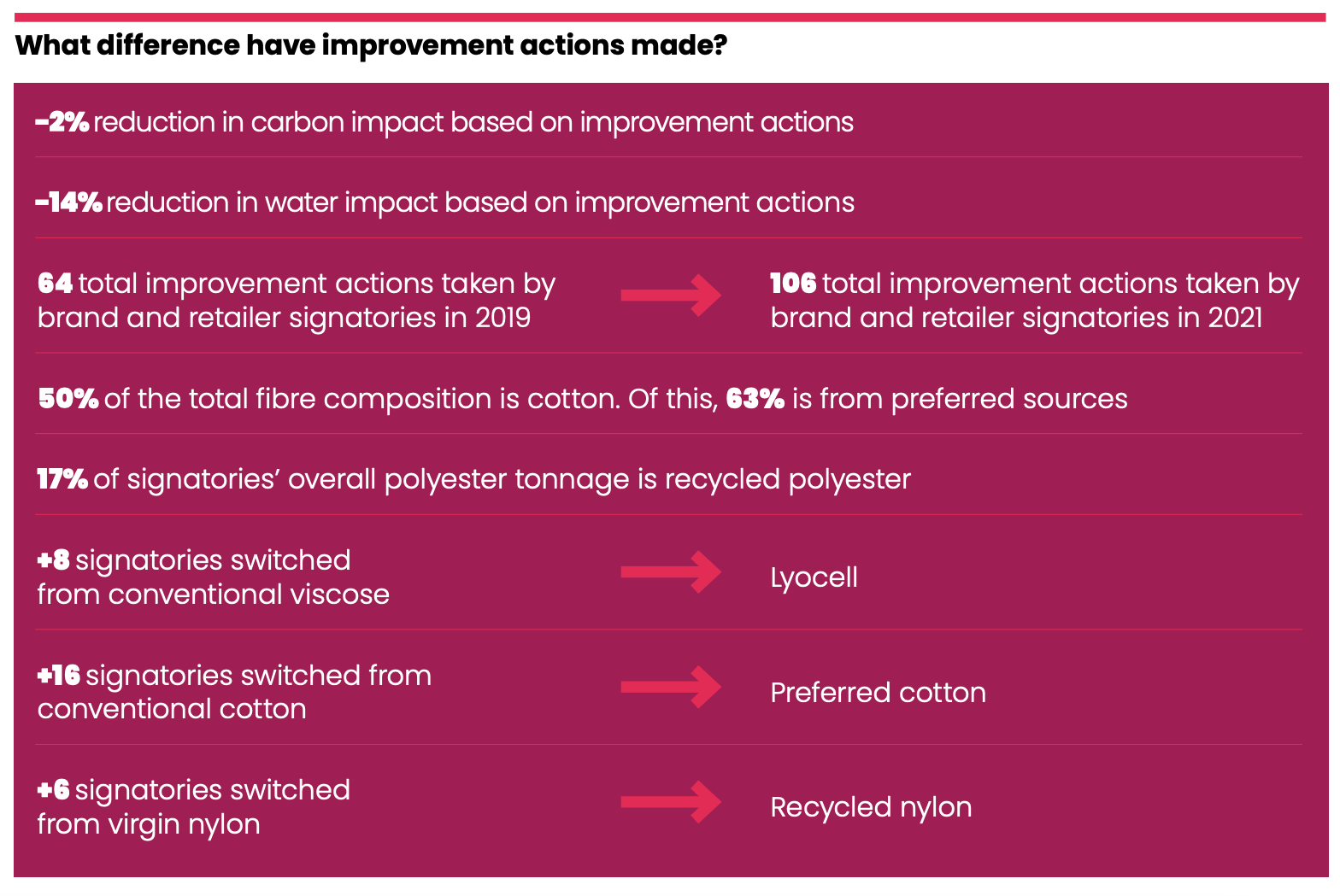

WRAP’s 2030 Annual Progress Report says a 12 per cent reduction in the carbon impact of clothing has been cancelled out by a 13 per cent increase in the volume of textiles produced and sold.

The planet is, quite literally, drowning in clothes. Through recycling programmes have existed for decades now, of the 100 billion garments bought annually, 92 million tonnes of them get thrown out.

By 2030, that figure is expected to increase by over forty million as production continues to surge (it actually doubled between 2000 and 2014) and with the average consumer purchasing 60 per cent more clothes annually but keeping them for half as long as they did 15 years ago.

It’s an environmental and social disaster that shows no signs of abating – despite Cop27 and the latest IPCC report urging the industry to change its ways – due to the US’, China’s, and Great Britain’s insatiable appetite for exporting used material to keep up with ever-evolving trends.

Even more concerning, however, is the fact that regardless of fashion’s albeit feeble efforts to confront this, we’re still nowhere near a turning point.

This is because, as revealed by WRAP’s 2030 Annual Progress Report, the industry’s push to reduce the carbon impact of the garments it sells is being undermined by an ongoing addiction to buying new clothes.

It found that, while brands signed up to its voluntary agreement had successfully cut both the carbon intensity and volume of water per tonne used in their clothing manufacture by 12 per cent, the volume of textiles made and sold during the same period had risen by 13 per cent, negating these improvements.