i wonder what Carl Jung would think about this.

![]()

“Are you introverted or extroverted?” asked my boyfriend’s childhood friend, taking a sip of his flat white.

We’d been introduced only an hour before, which is maybe why this question made me feel more self-conscious than it should’ve. On the other hand, when people have always labelled you ‘the life of the party’, how do you explain that you’re just not anymore?

Given that he’d known me for all of about 45 minutes, I answered honestly. “I suppose I’ve always come across as extroverted, but I feel more introverted inside.”

“Ahh. Extroverted introvert,” he nodded, apparently satisfied by what I felt was a wishy-washy answer.

Hearing my new personality type defined out loud did nothing for my understanding of what it means or why things shifted in the first place. But even Carl Jung – the Swiss psychiatrist who first categorised humans this way – had the wits to know these distinctions were dubiously rigid.

“There is no such thing as a pure introvert or extrovert,” he declared. “Such a person would be in the lunatic asylum.”

Well, that’s awkward. There probably was a time when Mr. Jung would’ve loaded me onto the next bus to the loony bin.

Throughout my late teens and early 20s, I thrived on being busy. My weekends were marked by dinners, parties, and endless streams of conversations with people I knew well, but often with those I knew only vaguely.

I’d aspired to a life full of different faces, places, and events that blurred into one another. I wanted to create a mosaic of experiences that I felt would constitute an interesting, rich, and well-lived time spent on Earth.

It was no issue to leave a 12 hour split-shift at the restaurant I worked at to meet friends at a nearby bar, flitting between groups of people we met there until 2am, only to do it all over again (admittedly in a more exhausted state) the next day.

I’d decide to move to a country where I didn’t speak the local language or know a single soul, armed only with three suitcases containing my whole life and the confidence that I’d be on my deathbed one day, relishing in never letting the opportunity to have a new and exciting experience pass me by.

Propelling me forward was the belief that if you didn’t say ‘yes’ to every invite or adventurous idea that came your way, you were missing out. The best things in life would happen without you – and to way cooler people.

Of course, each one of these decisions led me to friendships and memories I cherish to this day. Still, making them seems slightly insane to me now. I wonder how I had the energy for it at all.

Perhaps this shift is part of getting older and maturing, fast-tracked by the social implications of being locked indoors for two years by a global pandemic. Even so, it’s a surprise – especially to me – that my definition of ‘a good life’ could change so drastically.

Instead of feeling excited by invites to large social gatherings, the prospect alone would drain me. My self-assigned expectation to be on perfect form, when all I wanted was to chill out and enjoy my (overpriced London) rent, was overwhelming.

I’d fight it, begrudgingly force myself out, and often regret it – the need for peace and quiet waiting impatiently for me next weekend. Learning I could say ‘no’ wasn’t easy, and even now, doing so can rise serious guilt that I’m letting people down.

Eventually exhausted with being at the whim of every spontaneous invitation that might be extended to me, Do Not Disturb became my friend. I read more novels, got to gym classes more frequently, and attempted recipes I’d always wanted to try in my newfound free time. I started to let go of the sense that if I wasn’t constantly in contact with people, I would somehow disappear.

Your thoughts are allowed to untangle themselves when you’re not distracted by the noise of other people’s opinions or a need for validation. And in a world that’s always telling us to do more and be more, there’s a kind of rebellion in pumping the brakes.

Good old Carl Jung explained it best: “Your vision will become clear only when you can look into your own heart. Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.”

Maybe Carl was a little introverted himself.

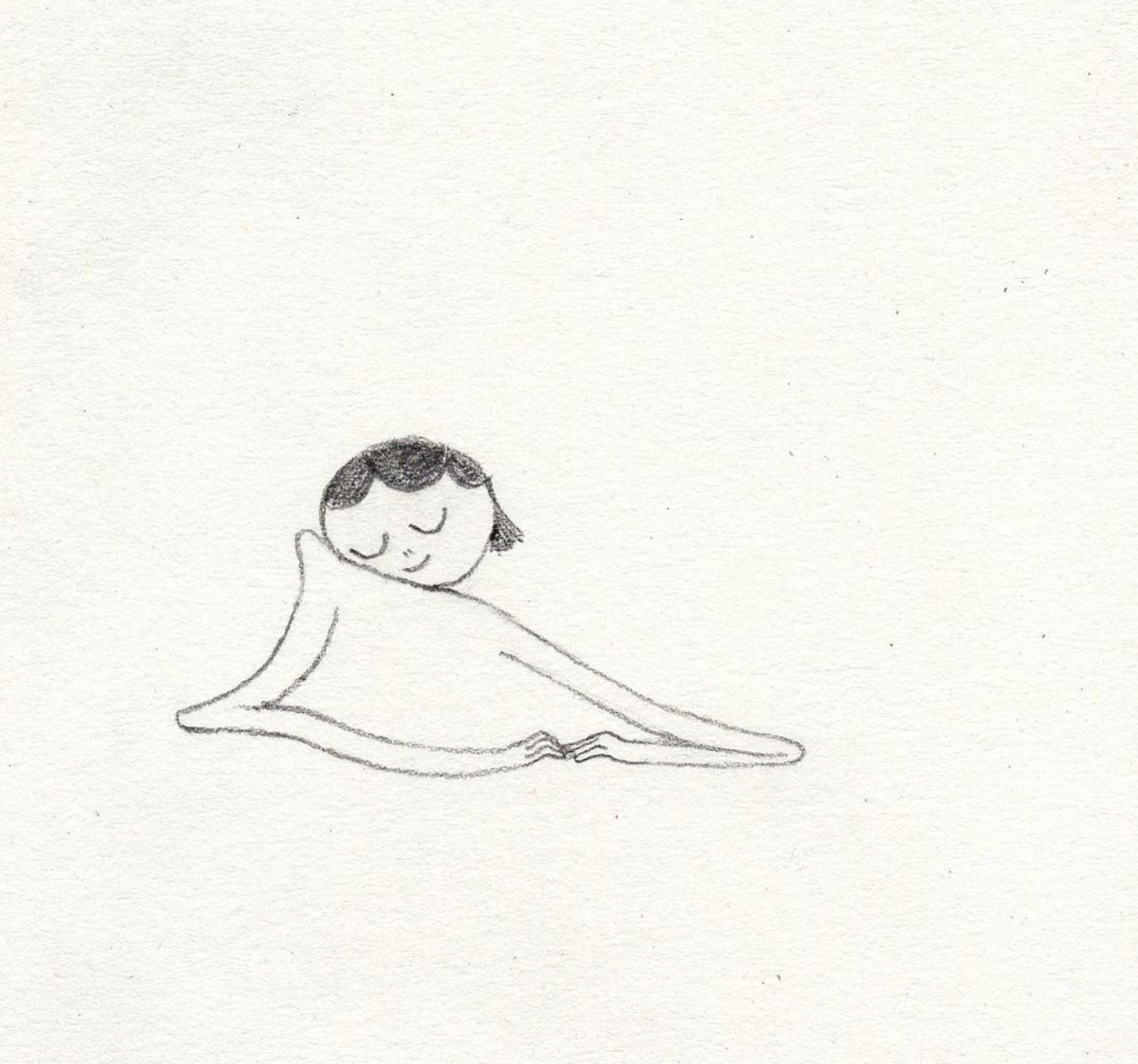

Many people mistake introversion for loneliness, but that’s not quite right. Loneliness is prone to surfacing when surrounded by people who don’t really see you. Introversion is like slipping into a warm bath — it’s comforting, it’s familiar, it’s where you can be completely yourself without the need to explain anything.

The best part of all, is that making time to recharge means the people I care about most get the best of me when I do see them, which is still often. They get the version that’s centred, with a fully-charged social battery, rather than the one that’s skittish, exhausted, and barely present.

I used to feel guilty or weird for needing alone time, as if it was something worth apologising for. But I’ve learned that introspective tendencies aren’t flaws. They help you move through the world with intention, choosing quality over quantity and depth over breadth.

There’s a joy that comes with waking up on a Sunday you’ve reserved just for yourself, and seeing the whole afternoon stretching out before you like an open road. In those moments, I’m reminded I don’t need a room full of people to feel alive, I just need the right ones.

And sometimes, that one is just me.