Money doesn’t grow on trees, but it can buy them

You guessed it, right?

The number one barrier preventing most governments from planting more trees in their capital cities is: the cost of the initial investment. But some leaders aren’t so short sighted. They’ve already coughed up the money.

Ana Luísa Soares, a landscape architect in Lisbon’s Ajuda Botanical Garden, has said that each new tree spotted in the Portuguese capital is indicative of an investment worth €2,000.

That four-figure sum includes the cost of the tree itself, but is mainly made up of maintenance expenses caused by the need to nurture a tree in its first, fragile years of survival – usually around five years.

Ana Luísa Soares points out that current economic uncertainty caused by inflation and war and the pandemic has made governments hesitant to fork out the cash on city-wide tree-planting projects.

But here’s a plot twist.

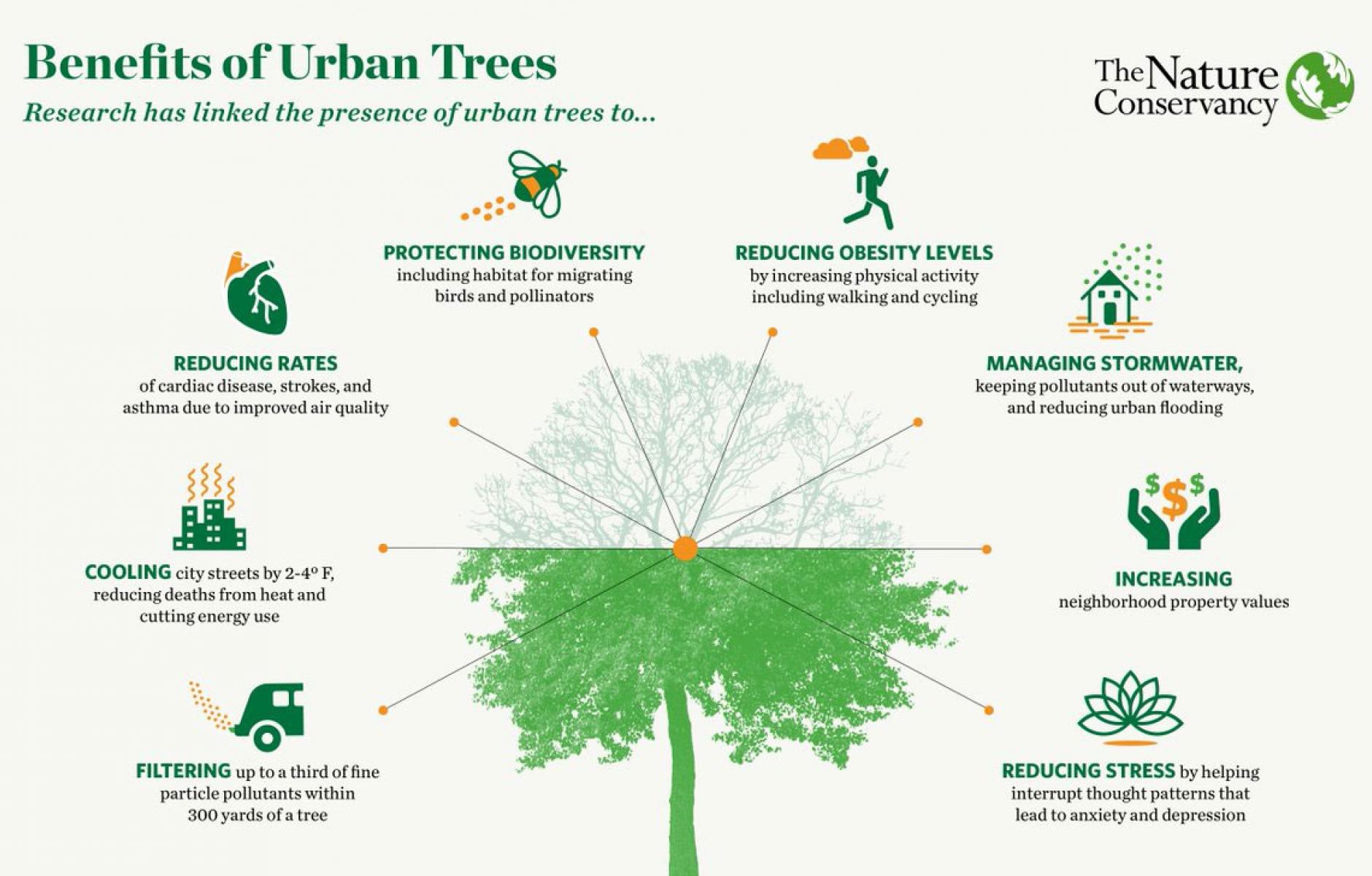

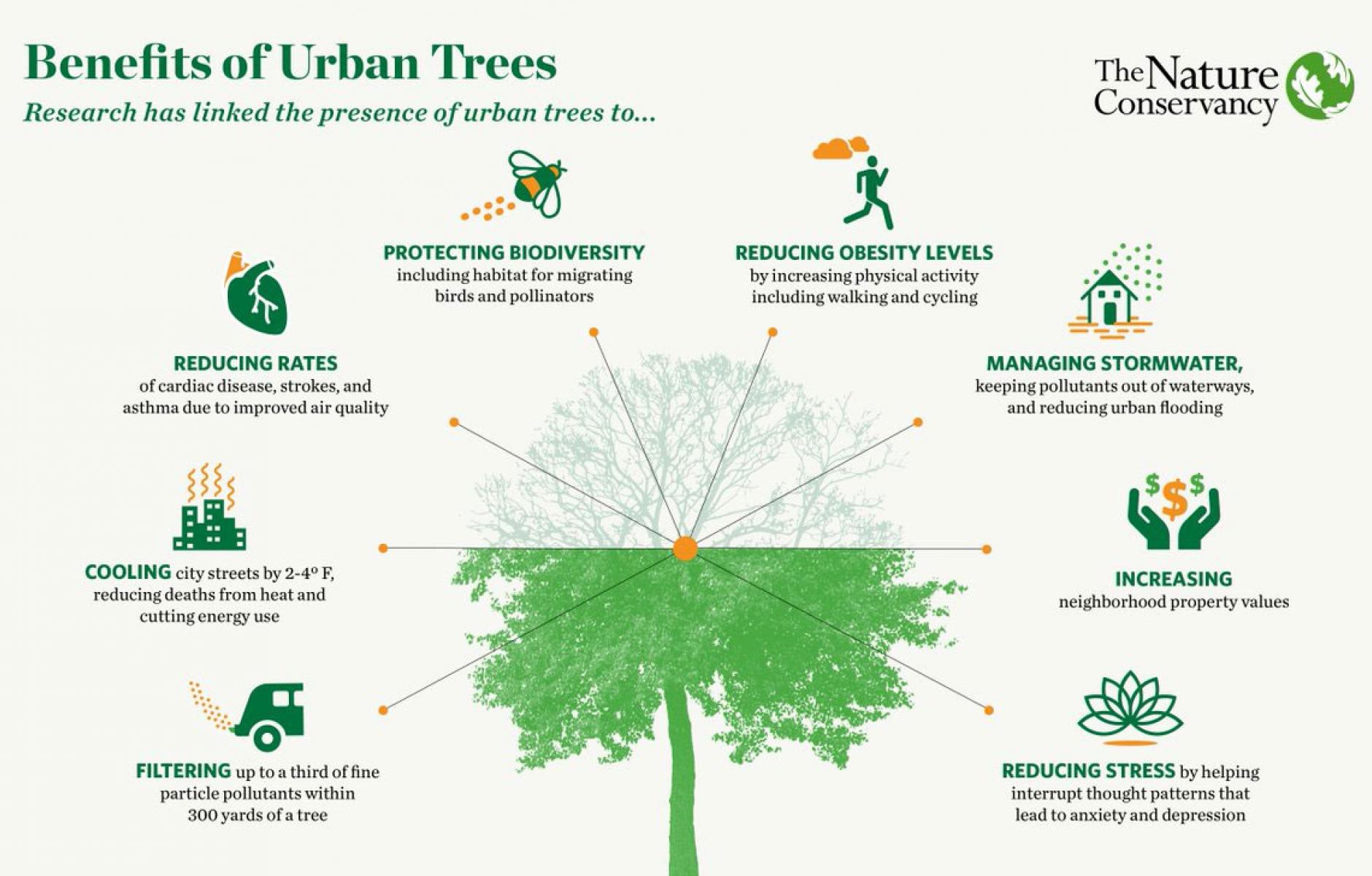

Adopting a US software program called iTrees, Soares analysed data from Lisbon’s 41,000 trees. The results showed that despite trees requiring about $1.9 million in government spending annually, the natural services they provide are worth around $8.4 million.

She broke down those benefits using the new data, stating that for every $1 a city invests into trees, residents gain around $4.50 in benefits.

For each tree planted, total energy savings sit at around $6.20. Carbon reduction services sit at $0.33. Meanwhile, reduction of air pollution saves governments $5.40 and a further $47.80 in savings on stormwater runoff control.

And because trees are pleasant to look at, they almost always increase the property value of houses and buildings on streets which they line. Visitors and residents of the city are also more likely to visit and shop in areas where tree-cover is abundant.

All of these things are good for the economy, meaning the short-term investment yields a long-term benefit. But there are physical barriers to tree planting in cities. Let’s look at those, too.

Physical barriers to tree planting

Of course, planting a forest on top of concrete will be a challenge.

Historical squares, high-rise buildings, concrete pavements, and car parks are not ideal environments for young trees to thrive. Soares says that trees need ‘at least 1 meter of subsoil’ between the concrete structures and the ground in order to grow successfully.

With many older trees reaching the end of their lifespan, EU cities have lost 10 percent of their tree coverage in the last decade. Replenishing greenery has been a challenge when young trees cannot survive amidst the abundance of concrete.

Today, demolishing the ground and digging further presents a huge risk, as most European capitals are home to a web of metro systems that snake beneath sites of interest, especially historical squares and iconic streets.

Acknowledging these challenges, Soares and other urban planners are adamant that we should not be discouraged. Instead of focusing on the areas where tree-planting isn’t an option, they say we should look to ‘the 90 percent of urban spaces that can and should be greened.’

So let’s get to it.

Getting to the root of it

By now, most environmentalists know that behind every viable climate solution they put forward, there is an old white politician in a suit, clutching his gold Amex card, ready to whine: ‘but that’s too expensive.’

It’s this short-sightedness that will see architects scrambling to concoct new, billion dollar ‘cool-skyscraper’ projects, force employees to work from home because public transport systems can’t operate in severe heat, and result in an unfortunate number of people dying from soaring temperatures inside their city apartments.

The good news is that the European Commission (EC) may soon force governments to reforest their urban spaces. Its representatives have proposed a law that forces member countries to dedicate a minimum of 10 percent of their cities, towns, and suburbs to green canopies by the year 2050.

Though still in its draft stages, the law encapsulates the EC’s goal of accelerating nature restoration as a whole, and would also commit member countries to maintaining their existing urban green space.

This is great. But looking at the drastic heatwaves Europe is facing right now, 2050 seems like a target set way too far ahead. We need to ramp up action that sees this low-hanging fruit of a solution become our reality now.